People wearing protective gear wait in line to be tested for the coronavirus (COVID-19) outside Elmhurst Hospital Center in the Queens borough of New York City March 25. (CNS/Reuters/Stefan Jeremiah)

Just recently, I was at the grocery store, and as I checked out, I thought about the workers there who were serving us. I thanked the clerk who had just rung up my purchases. Her broad smile indicated that not many people had acknowledged her sacrifice and commitment.

That encounter made me think of others, including first responders, health care providers, delivery people and others who return to work every day, risking their own health to provide the necessities of life for the rest of us.

The need for other sacrifices is just beginning to emerge. Shortages of equipment, medications and even personnel will force us to ration care and medical resources.

The thought of rationing horrifies us. It has been a major obstacle to health care reform; politicians don't even like to use the word "allocation," let alone "rationing." No one wants to admit that all precious resources are limited. Most of us are accustomed to plenty and being able to simply buy what we need, so the thought that there might not be enough for everyone is almost beyond our imagining. The hoarding of toilet paper might make us feel we are in control, but it is an absurd example of how unprepared our consumerist selves are for these challenges.

How should we as Christians think about this spiritually? Let me cite a few principles from Catholic social teaching and then make a few practical suggestions for a spirituality appropriate to a time of scarcity.

First, we must safeguard human dignity, which is shared equally by all of us. Our health, our wealth, our social standing may vary, but our dignity as persons is from God. It is inherent, not arbitrary.

The paradoxical thing about human dignity is that while it is personal and unique to each of us, we can't experience it apart from our connections to others. In his New York Times column on March 20, David Brooks said:

Through plague eyes I realize there's an important distinction between social connection and social solidarity. Social connection means feeling empathetic toward others and being kind to them. That's fine in normal times.

Social solidarity is more tenacious. It's an active commitment to the common good — the kind of thing needed in times like now.

This concept of solidarity grows out of Catholic social teaching. It starts with a belief in the infinite dignity of each human person but sees people embedded in webs of mutual obligation — to one another and to all creation. It celebrates the individual and the whole together, and to the nth degree.

Solidarity is not a feeling; it's an active virtue. It is out of solidarity, and not normal utilitarian logic, that George Marshall in "Saving Private Ryan" endangered a dozen lives to save just one. It's solidarity that causes a Marine to risk his life dragging the body of his dead comrade from battle to be returned home. It's out of solidarity that health care workers stay on their feet amid terror and fatigue. Some things you do not for yourself or another but for the common whole.

Solidarity is elegant theory, but there are times like ours when the rubber hits the road as we are called to share the suffering and the risk of others to whom we are tied by our common human dignity. We are in this together.

Solidarity involves resources, too. The goods of creation, including medical knowledge and technology, belong to all of us. Yes, there are patents and licenses and academic degrees that give us a certain kind of ownership of knowledge or skills that we worked hard to acquire. But when our knowledge and skills touch the essentials of human life and the common good (e.g., food, water, medical skills, ministerial training, political life) ownership is relative. It carries a kind of social mortgage.

I might have radical ownership of my car or my IRA account, but not the learning I acquired for service to others.

Advertisement

Subsidiarity is another important component of crisis spirituality, especially with regard to "who decides" and "who allocates". Some societies use central authority far removed from the populace to made decisions about allocation of scarce goods. In the Catholic view (and generally in the American view) participation is paramount. Civil leaders are entrusted with the final decision, but their decisions must stand on the firm ground of maximum participation and transparency.

These principles set the stage for hard decisions about allocation. There are at several ways to do this. We could just say "first come, first served," or use a lottery, or allocate on the basis of ability to pay, or by need (i.e., who is the sickest).

As Christians, we would rule out both "first come" and lottery as irresponsible and haphazard. Ability to pay is an affront to human dignity and equality. Treating the sickest first would be appropriate if the shortage were temporary, but that may not be the case. What if the shortage of medicines or equipment were long-term?

In the case of such shortage, as it appears to be with ventilators, hospital beds and even providers, then we are dealing with another situation entirely. A long-term shortage will require us as a society and as providers to allocate not on the basis of who can pay the most or who gets there first, but on who can benefit most, that is, who is most likely to recover with intervention. In addition, we will have to make sure that we do not discriminate against the elderly, poor vulnerable or disabled just because they are elderly, poor, vulnerable or disabled. There may be cases in which someone old or not fully able can actually benefit more from hospitalization and respiratory therapy than someone younger or more fully able.

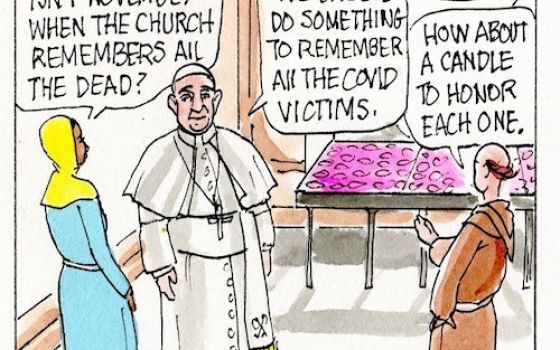

Spirituality in the time of scarcity must also involve contemplation of mortality. Thousands have already died of COVID-19, and many more will die before we are through this crisis. St. Benedict reminds us to "keep death ever before our eyes," and this is invaluable advice for us today.

Entertaining death as a companion is not easy, but it is essential. It need not be morbid or despairing, because our ultimate hope as Christians is eternal life. This is a very good time to pick up some meditation on death (the letters of St. Paul, especially 1 Corinthians 15 and 2 Corinthians 4-6 are good places to start).

If you need a prompt there is a virtual memento mori app called "WeCroak" that will message you five times a day, inviting you to stop and think about death. "Find happiness," it says, "by contemplating your mortality."

Finally, our spirituality must invoke selflessness and the common good. Maximilian Kolbe was a Franciscan friar imprisoned at Auschwitz. When 10 prisoners were selected to be starved to death as a deterrent after an attempted escape, Kolbe volunteered to take the place of a married man with children.

His example compels me to wonder about my own selflessness. I have lived a very blessed life. I don't consider myself "elderly," but in my late 60s, I am definitely knocking at the door! Could I forego the use of a ventilator if I knew that there were younger people, perhaps fathers or mothers, who would benefit more? Morally, yes. It would be heroic virtue on my part. Would I have the courage to do so? That is another question.

The time of confinement we have entered is unprecedented. It is frightening and uncertain, but it is also an extended retreat from the business of our lives. We are self-distancing, but we must also draw closer to one another and to the God who saves. Let us use this time to reflect on mortality, the common good, selfless sacrifice, and especially our common life and common destiny.

[Dominican Fr. Charles Bouchard is senior director of theology and ethics at the Catholic Health Association of the United States.]