(Pixabay/bernswaelz)

Helena* was a teenager experiencing financial hardship when her friend's father invited her to move in with their family. Since this made it possible for her to seek a better job, she accepted. He told her to consider herself a member of the family, which at first made her uncomfortable, but she got used to it. Now, she realizes this was grooming.

Helena stayed with the family for a few years. Then, when she was in college, the man offered to help her dress in a way that was both modest and flattering, so she would be able to find a husband. "I was devout and craved love and romance," Helena wrote in an email interview. "So I was all for it!"

Emphasis on modest dress, especially for young women and girls, is a key element of purity culture, a Christian subculture that originated with evangelicals but is present in conservative Catholicism as well, especially with the rise of the "trads." Purity culture insists on rigid gender roles and abstinence-only sex education, stressing the importance of marriage and family, especially for women. Modesty is important in this culture because of the belief that men are "more visual" and must be protected from falling into the sin of lust.

Purity advocates also claim that women will be safer if they dress and act in "traditional" ways. It's a trope in the culture war: women tell the stories of how they were harmed, and conservative Christians tell them they have only themselves to blame for not being pure and modest enough. Recently, in response to the "man or bear" thought experiment, an account called "Ancient Masculinity" on X, formerly Twitter, posted multiple images of demure women in veils and dresses, accompanied by such statements as "if women would start dressing like this … they would instantly attract more noble minded men." Some statements read as threats: "While women may not always realize it, opposing the patriarchy actually threatens their very existence in a profound way."

(Pixabay/geralt)

The man who groomed Helena was highly esteemed in his community and active in his parish. And his fixation on modesty became his excuse to comment about her body, touch her and ask her to try on different outfits. Once, she caught him watching her change her clothes, and confronted him, but he assured her he would never do something so crude.

"I believed him, because I needed it not to be real," she wrote. Another time, when she was about to take a shower, she found a camera in the bathroom. The man said one of his teen sons must have planted it, and waved the incident off, saying, "men and women are different."

One night, the man got drunk and tried to force himself on her. "After I got his hands off me, he apologized," she wrote. "He said that I tempted him and as a man, he couldn't control himself. He couldn't help but lust for a girl he wasn't really related to." Sometimes, she said, the man would talk about young women in the past who had tried to "frame" or "seduce" him.

By now, Helena realized she was being abused. She was able to move out, but continued to feel shame. "I truly believed that I was afflicted with something," she wrote, "or [had done] something so sinful that made me the only thing in the world bad enough to make this holy man do such nasty things."

"I truly believed that I was afflicted with something, or [had done] something so sinful that made me the only thing in the world bad enough to make this holy man do such nasty things.'

—Helena, who shared her story with NCR

Finally, she told a few friends about how the man had abused and manipulated her. A few months later, another young woman reached out to her, because the man was messaging her, offering the same "help" he'd given Helena. She remembered the stories about girls framing him. "The veil dropped and I knew he was actually the one at fault for everything," Helena wrote.

Helena is only one of many women and girls who have found themselves less safe, not more, in subcultures that emphasize purity and modesty. Sarah Stankorb, author of Disobedient Women, has spent years compiling the stories of women who spoke out about abuse within their conservative evangelical communities. "I've reported on many situations of girls in abusive situations with clergy, which were later described as 'an affair,' " Stankorb said.

Stankorb pointed to several cases of high-profile evangelicals who fixated on purity and turned out to be abusers. Obsession with physical modesty standards creates a culture in which men feel entitled to control women and their bodies. One example is Robert Morris, a former evangelical adviser to Donald Trump and founder of Gateway Church, one of the largest megachurches in the nation. In the 1980s, when Morris was in his 20s, he began molesting a 12-year-old girl. "Counseling was offered to the perpetrator in the case, not the victim," Stankorb said.

Stankorb also brought up Bill Gothard, founder of The Institute in Basic Life Principles, which gained notoriety following the 2023 documentary series "Shiny Happy People." "He was a prolific speaker and writer," Stankorb said of Gothard. "He produced so many books that included warnings about eye traps, pages of diagrams about the length of a woman's hair, what her neckline should be like, what kind of jewelry she should wear, nothing that draws the eye down to her chest." Gothard would visually assess girls and young women, to make sure they were conforming to his standards. "When you hear about the number of allegations against this man," Stankorb said, "To me this was a masterful grooming process, he gave specifications for the type of girl he sought to surround himself with and behave inappropriately with."

Emphasis on obedience, Stankorb said, makes it easier for predators to have their way.

Emphasis on obedience, Stankorb said, makes it easier for predators to have their way. She brought up the case of Andy Savage, who resigned from his position as pastor of Highpoint Church in Memphis, Tennessee, following allegations of sexual assault of a minor in 1998. Savage was Jules Woodson's youth pastor and sexually assaulted her when driving her home from church.

"He asked for oral sex," Stankorb said, "and she assumed that if he was asking this he must want to marry her. He was the minister, she was taught she had to submit."

Of course, abuse of women occurs everywhere. But purity culture makes it harder for women to protect themselves, hold abusers accountable or even identify abuse when it occurs. According to Angela Denker, who has done extensive research into conservative religious spaces in the United States, purity culture "draws inspiration from this general sense that the outside world is dangerous." In these closed communities, young women have few resources for reporting abuse, and the burden is on them to police sexual morality. "I've experienced what that's like, for a teenage girl or young woman," Denker said, "feeling my sexuality is dangerous or something to be ashamed of."

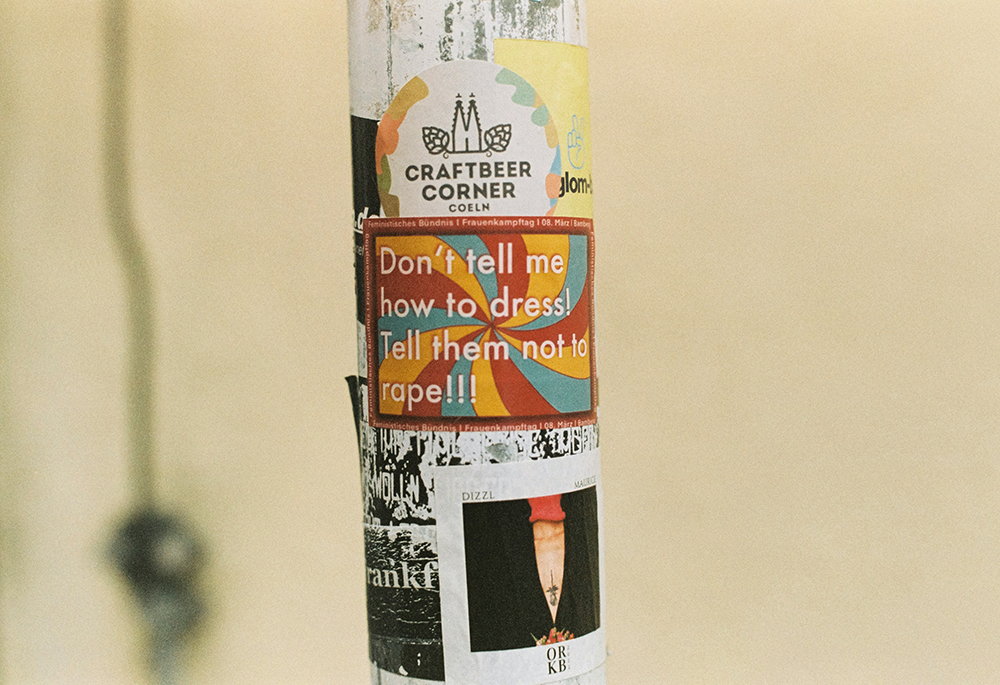

This, she said, feeds into rape culture, with questions like "What was the woman wearing when she was brutally raped while incapacitated?" Women so often get the blame for forbidden sex acts — even when they are the victims of assault.

(Unsplash/Markus Spiske)

This was what Ollie experienced while attending the Franciscan University of Steubenville. Ollie identifies as nonbinary, but was not out at the time. Their then-boyfriend, T, was a few states away, having been rejected by seminary for poor mental health. Both were from conservative backgrounds. T confided in Ollie that he was struggling with a porn addiction and compulsive masturbation. He decided that sex acts between two people were more "natural" and thus morally preferable to those that happened solo. "That rationalization," Ollie said, "led him to believe that coercing me to perform sex acts on him was somehow better than him jerking off alone." During winter break, T began forcing Ollie into various sex acts. A few months later, this escalated to full penetrative sex.

After returning to campus, Ollie realized that what T had done was abuse and went to their dorm chaplain, Father Luke. "I was so overcome with feelings of guilt and violation, and tried to convey the nuance of our situation through sobs," Ollie said. "But all he heard was that premarital sex had occurred, and I needed to confess that sin more than anything." Robertson did not refer Ollie to a counselor or follow up in any way. "Father Luke is a licensed social worker and should've known better," said Ollie.

Women and others who have been abused in these traditional spaces are often treated as though they, not their abuser, is at fault. And even when the fault is recognized, there is often pressure on women not to talk about it, since that would be "gossip" or "slander." They are expected, as Kaya Oakes points out in her book Not So Sorry, to forgive and forget. The abusers move on, but the victims have to deal with their trauma for years, often in silence. Many realize that even if they speak up, no one will take them seriously.

Denker noted that many women who grew up in conservative religious cultures are still attempting to recover from its effects. "A coping mechanism in abusive cultures is disassociation," she said. "It creates this separation of women and girls from our bodies." Women in their 30s and 40s are still trying to recapture a connection to their bodies that was denied them in their younger years.

Women aren't the only ones harmed by purity culture. People who identify as LGBTQ+ are often shamed for failing to conform to gender stereotypes and subjected to additional harassment and abuse. And even though the culture privileges straight white men, they suffer in it too. Denker, whose book Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood is forthcoming from Broadleaf Books in March 2025, noted that the culture infantilizes boys and men.

"They are incapable of understanding their own choices. Purity culture takes away agency and creates a narrative that becomes unsafe for everyone involved." She noted, too, that strict gender roles do not make for healthy relationships. "Saying something is always true for boys or always true for girls is not good for anyone; it creates barriers for relationships, where people act according to their gender roles instead of communicating openly. It leads to a lot of despair and loneliness, especially for white Christian men."

But this isn't just some modern American evangelical phenomenon spilling over into Catholicism. Purity culture has its roots in ancient prejudices about women and the body that predate Christianity. It is not a fundamentally Christian ideology — if by Christian we mean "aligned with Gospel teachings" — but that hasn't stopped Christians from embracing it. The reality remains consistent, from the days when the church fathers wrote about women as sources of temptation to the present age, when sexual predators are feted and protected while their victims are punished and shunned.

In Catholicism, ideologies related to purity culture have influenced our cult of virgin martyrs, a category of sainthood reserved only for women. According to their hagiographies, these women were brutally murdered because they refused to submit to male lust. In these stories God miraculously intervenes to protect these women from being raped, but rarely saves them from being murdered. Today, conservative Catholics revere these victims, not as people who were courageous against injustice but as women who "died to protect their purity" — the presupposition being, apparently, that if they had been raped, they would no longer have been pure.

Advertisement

Purity culture does not make women safer. On the contrary, the mechanisms that allow for abuse, manipulation, cover-ups and victim shaming are built into it. Abusive leaders continue to thrive, thanks to purity culture's precepts, as do the institutions that shelter them. And at this point, it's a whole industry, as Stankorb pointed out: "People are making a lot of money selling the Bibles, the books, the swag." Megachurches continue to rake in money, and parents continue to send their children to conservative Christian colleges, despite knowing about ongoing abuse.

Christians and others who push back against purity culture, and the rape culture connected to it, may feel that their efforts go nowhere. Whistleblowers can devote years to raising awareness about clergy abuse, or cover-ups in conservative Christian institutions, only to see their fellow Christians ignore the revelations of wrongdoing and enthusiastically prop up harmful institutions.

Nevertheless, the fact that these conversations are happening is encouraging. Women are telling their stories to one another, and sometimes finding the empowerment they need to tell them to the world. Books like Disobedient Women, Not So Sorry and Disciples of White Jesus are being written, published and read. And as women who were harmed by purity culture speak out, they also are helping younger women recognize and name abuse, access resources and take ownership of their bodies.

"Girls and young women need to get information about their bodies. Exploring and understanding their bodies, that is powerful," Denker said. "It's also an article of faith: to embrace and love your body is to embrace and love God's creation."

*The name has been changed, to protect the source's identity.