Fr. Stephen Saffron, parish administrator, prays during a traditional Latin Mass July 18 at St. Josaphat Church in the Queens borough of New York City. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

During the summer of 1968, I attended the University of Notre Dame and took the first two of the courses required for a master's degree in liturgical studies. One was about liturgical books and sources, taught by Benedictine Fr. Aelred Tegels. Repeatedly, he brought to our attention that almost all the prayers in these sources were in the plural — quaesumus — "we ask."

The other course was on the Eucharist and taught by Benedictine Fr. Aidan Kavanagh. One of his repeated refrains was that the Eucharist as the body of Christ always builds up and serves the body of Christ, the church.

When I returned to seminary for my second year of theology, I met the moral theology professor in the hallway. He said, "Say something to me in liturgy."

I replied, "Church." That is what I was taught that summer and have kept learning and teaching to this day. Liturgy and church are inseparable.

I offer here a few thoughts that contextualize and explore Pope Francis' July 16 apostolic letter Traditionis Custodes, which reimposes restrictions on celebrations of the Mass according to the pre-Vatican II Latin rite.

Pope Francis celebrates Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican June 6. (CNS/Reuters pool/Giuseppe Lami)

A papal triptych

Amid all the discussions about the papacy in recent years, I find it helpful to regard St. John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis as a papal triptych. Each brought his particular strengths to the papacy and specifically to the issue of church unity.

No pope wants to have a schism as part of his legacy. John Paul II saw that as a serious threat from the followers of Marcel Lefebvre, who taught that the Missal of Paul VI, issued in 1970 following the end of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), was heretical. They also found the council's overtures to other Christian churches, communities and interreligious dialogue were deeply flawed and suspect, in effect heretical.

Therefore, John Paul II extended a very significant olive branch to the Lefebvrites in 1988 to celebrate the pre-Vatican II missal under certain restrictions. Overnight, the issue of the missal revised after Vatican II was off the table.

Interestingly, the title of the document giving this permission is "The Church of God" (Ecclesia Dei) and not for example, "The Liturgy of God." This is the same name John Paul II gave to the commission whose competence was to work toward reconciliation with the Lefebvrites. The permission about the Mass was about the church and the restoration of church unity.

Mass and church teaching

In the fall of 1996, I was residing at St. Mary Mother of God in downtown Washington, D.C. One Sunday morning, I was going to take a run on the National Mall. My exit from the building coincided with the arrival of the community that would gather for the 9 a.m. Tridentine Mass in Latin.

One gentleman asked whether I would ever celebrate "their" Mass. I replied that I could not because I did not have the archbishop's permission. It turns out that almost all of those who attended were from the Diocese of Arlington, Virginia, because the bishop of Arlington at the time, John Keating, did not allow the Tridentine Mass at all.

After the Mass, the children attended catechism class but the text was the Baltimore Catechism (first edition 1885). Hence, there was no teaching from Vatican II or the social encyclicals.

I judge that Francis' concern about doctrine is very deep and very real. He requires that those who celebrate the Tridentine Mass must accept "the binding character of Vatican II."

The phrase lex orandi, lex credendi (what we pray is/should be what we believe) had had a certain resurgence during the debates about the English translation of the Roman Missal. In his apostolic letter Traditionis Custodes, Francis reasserts that the liturgical books approved by Pope Paul VI and St. John Paul II "constitute the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite."

Advertisement

Gone are the grammatical acrobatics that required the use of phrases like "the ordinary form," "the extraordinary form" and "the novus ordo" — not to mention the sleight of hand when church signs or bulletin mastheads noted a "Latin Mass" was available, when what they were really saying that the then extraordinary form of the Mass was to be celebrated.

'Mutual enrichment'?

When Pope Benedict XVI in 2007 issued his apostolic letter Summorum Pontificum, expanding the occasions when what the pope termed the "Extraordinary Form of the Mass" could be celebrated, he also issued a letter to accompany the document.

In that letter, Benedict indicated that he could envision a "mutual enrichment" of the Mass from 1570 and the Mass from 1970. I read this with complete surprise.

Who would decide what elements and on what basis? Did not Benedict severely criticize the "picking and choosing" that was going on in the 1960s and quite correctly so? I can recall seeing clandestine prayers circulating to replace the texts of the missal for the day. (That was in a Xerox copy culture. I can only imagine what can and does happen in an Internet culture.)

Liturgy is like putting your hand in a glove and being in a familiar place and space. It is not reinventing the wheel according to whims and individual likes or dislikes. Liturgy is.

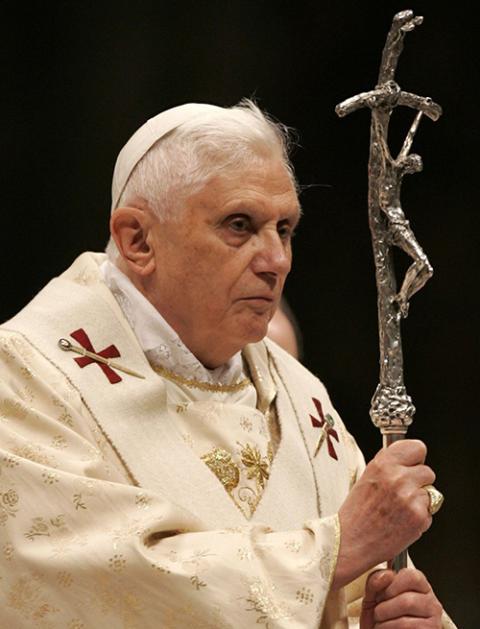

Pope Benedict XVI celebrates Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican on Dec. 25, 2007. (CNS/Reuters/Max Rossi)

Honestly, by this time of Summorum, the wind had gone out of the sails about the Tridentine permission for reconciliation with the Lefebvrites. But it was curious that Benedict noted that a number of young people "feel" drawn to this form of the Mass. The phrase is "felt its attraction" (Italian: "anche giovani persone scoprono questa forma liturgica"). Since when does an official church document about the liturgy concern one's feelings to be drawn to Mass A or to Mass B? Liturgy is.

When the Kennedy Center opened in D.C. 50 years ago, the premier performance was the newly commissioned Mass by Leonard Bernstein. Within about five minutes into the piece, the orchestra stops abruptly and a soloist sings something that is the exact opposite of the Mass. He sings, "Make it up as you go along."

That is the complete antithesis of what liturgy is about. In fact, we do not plan any liturgy. We should prepare for every liturgy. Sadly, some of the things we should prepare very carefully are things that surveys of American Catholics repeatedly criticize: the quality of homilies and music.

Among the first instances of the Tridentine Mass being celebrated in D.C. was at the prompting of Republican presidential candidate Pat Buchanan in 1992. In his book Right From the Beginning, Buchanan said that even during the Tridentine Mass he would read a book during the homily because after Vatican II the Catholic Church had become "the First Church of Christ Socialist."

So much for the Holy Spirit guiding the bishops as teachers at Vatican II. At the same time, Buchanan may have been ahead of his time by hiring a priest to celebrate "their" Mass in a high school chapel. I regret to say it, but I can sadly envision the volume of requests that those who want the (then) extraordinary form to be celebrated will make of schools and seminaries.

The fact that from now on a seminarian seeking to celebrate the Tridentine Mass needs the permission of the Apostolic See means the pope regards this restoration of the Vatican II liturgy to be of the utmost seriousness. In effect, this will dry up the supply of priests trained and willing to celebrate the Tridentine Mass.

Some will say (and have already done so in blogs) that this decision will cause a schism, the kind of thing John Paul II wanted to avoid in the first place. But my opinion is that whatever actions people take will simply unmask the silent schism that has taken place and continues in the American Catholic Church over a number of things, including liturgical preferences.

Back to Notre Dame. The basic premises are about the "we" in "we ask" and that the body of Christ in the Eucharist feeds the body of Christ the church. In effect, we are in this together.

How does that play out in a culture that has moved from "People" to "Us" to "Self" magazines and presumes that the national anthem is "I Did It My Way"?