Justice William J. Brennan Jr. holds his daughter, Nancy, as his wife, Marjorie helps him with his robe at the Supreme Court building in this 1956 file photo. Brennan died July 24, 1997, at age 91. (CNS file photo)

In January 1963, my mother, then 13, attended a Red Mass at Washington's St. Matthew's Cathedral with her father, Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr., and her mother, Marjorie. During the homily, the bishop presiding at the Mass criticized justices, including my grandfather, who opposed laws that mandated prayer in public schools.

My grandparents were active Catholics, and my mother had attended parochial school. Marjorie's childhood photo album included a picture of no less than eight habited nuns and a priest picnicking on her front lawn. As they left the Red Mass, my grandmother gave the bishop a quiet but decisive verbal rebuke. My mother was distraught, convinced that the prelate had threatened her father with excommunication. They effectively stopped going to church.

Catholicism was at the core of the culture in which my maternal grandparents grew up. My grandfather's jurisprudence grew out of Catholic and biblical social values such as human dignity, justice and societal protections for the poor, oppressed and marginalized. His parents had emigrated from Ireland, and they were also observant Catholics, active in civic life.

My great-grandfather William J. Brennan Sr. went from leading his local union chapter of brewery "stationary firemen," to holding elected office in Newark, New Jersey. Reading his obituary would give you the impression that every Catholic religious leader in New Jersey was at Bill Sr.'s bedside when he died in 1930. It sounds trite to our modern ears, but my great-grandparents obtained in America that ever-fragile combination of religious freedom, civic engagement and ability to organize for a decent standard of living that was out of reach for them in Ireland.

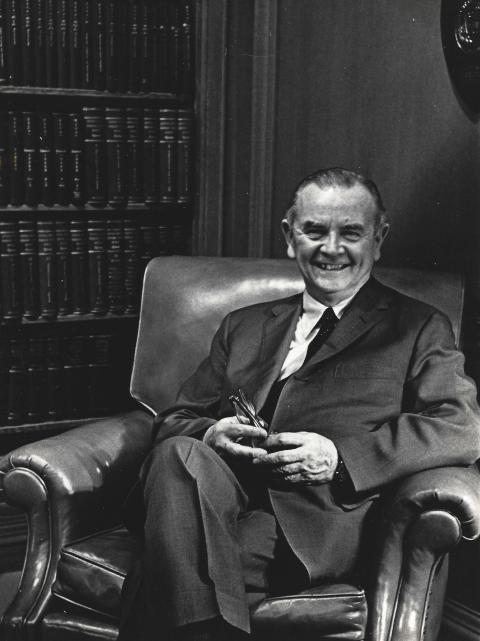

The late Justice William J. Brennan Jr. in his Supreme Court chambers (Courtesy of Constance Phelps)

As a Supreme Court justice, my grandfather had to don a thick skin and apparent imperviousness to criticism or popular opinion. But he continued to seek out and enjoy the company of clerics his whole life — much as his own father had — so rejection by Catholic officials must have smarted. I believe that his peace lay in knowing the difference between the politicized and heavy-handed mandates of institutional Catholicism, and his own morality guided by the small "c" catholic church, meaning "universal."

Also in the 1960s, but in a very different place, my paternal grandfather Walter Phelps, president of his small-town school board, was criticized in a homily for spearheading an effort to have a public high school built. It would reduce the enrollment of the local Catholic school, said the priest. His wife tried to continue going to Mass by driving her family 40 minutes away, where they could feel safe from shaming.

Reactive, extremist and politically motivated ideology contributed to an eventual religious alienation from Catholicism on both sides of my family: among the next generations of seven children, 13 grandchildren and dozens of great-grandchildren.

The institution of the Catholic Church in America has self-destructed, one lost family at a time, with an almost insistent and angry determination. The religion that we followed for millennia is still hostage to mortal men who do not represent transcendence or mercy, but power and control. After everything Catholicism has gone through, many of its leaders continue to act from breathtaking arrogance, as if they actually owned our very connection with God — without care for our daily lives or our spiritual needs.

The threatened exclusion of people in public office from the sacrament at the heart of Catholicism would not only affect President Joe Biden, but also senators, House members, those on the Supreme Court and thousands of Catholics who serve in local public office around the country.

Advertisement

We will once again be called "papists," and opponents will justifiably claim that we cannot both uphold the Constitution and belong to our religion. The "leadership" is inexplicably making us choose between being American and being Catholic. This is an attack on all the laity by the same prelate culture that has been dismantling our religious life brick by brick for decades, with a bizarre mix of scandals, doctrinal rigidity and emphasis on political clout, over the grace and beauty in our everyday traditions and worship.

To my knowledge, I have few relatives who regularly attend a Catholic church. Mass is essential to my life, though I had to be confirmed as an adult, as I had grown up basically without religion. But now it may be robbed from me again. How can I belong to a denomination that might have denied its most essential sacrament to my grandfathers, as they acted on their core beliefs about what was best for society as a whole on controversial issues of the day?

Last Sunday, as I took the Communion wafer in my hand, I said to the archbishop who gave it to me: "I know this comes from God, not from you." It was not a personal statement against him; it was about affirming a simple truth that should itself stop the cycle of religious alienation that clerical overreach has caused in my family, in our country and in me directly.

After I spoke, not turning away from the altar but stepping to the side of the archbishop in order to bow to it and place the wafer in my mouth, I felt some of my grandparents' pain lift from my shoulders.

[Constance Phelps is a social worker and mother living in Maryland.]