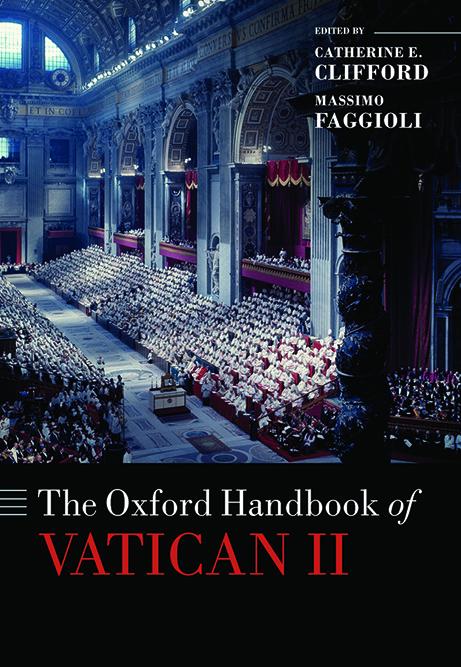

The opening session of the Second Vatican Council in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican Oct. 11, 1962. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo/Giancarlo Giuliani)

The Oxford Handbook of Vatican II attempts a Herculean task. Part reference book, part introduction to a complex historical subject, part analysis of a still ongoing reception of the conciliar teaching, part international symposium, this Hydra of a book proves to be a Herculean achievement. Those in the English-speaking world who teach Catholic theology now have a book at hand that comprehensively considers virtually every important post-conciliar subject, filled with references and additional resources, against which scholars and average Catholics can crosscheck their arguments and intuitions.

Cover to 'The Oxford Handbook of Vatican II' (Courtesy of Oxford University Press)

The first section of the book looks at the context and the sources of the Second Vatican Council itself, and the first chapter was penned by the late Jesuit historian John O'Malley. "Vatican Council II did not fall out of the heavens," O'Malley begins. "Like any institution and most especially any institution of the Catholic Church, the council can be understood only in the context of the situations and the issues it inherited from the past that the fathers of the council decided to address."

As in his entire career, in this chapter O'Malley's interpretative analysis would not come as a surprise to the subjects about whom he writes. Put differently, O'Malley eschews ideology and his narrative builds from his sources, it does not obscure them or force them into an analysis that is quite distinct from their own experiences and views.

O'Malley's summary of the approach the Council of Trent took to its urgent task of responding to the Protestant challenge will be well known to those who have read his book on that council, as will his assessment of Vatican I. What is remarkable here is his concise, conceptual analysis of the challenges the church faced during the Enlightenment and the development of theological ideas and movements between the first and the second councils held at the Vatican.

For example, in addressing the situation of 18th-century Gallican theology, which de-emphasized the significance of the papacy relative to the national church, O'Malley observes: "No matter how legitimate were the theological principles the Gallicans espoused, kings and their ministers co-opted them to promote the ideal of national churches only tangentially related to the Holy See." He notes that the Synod of Pistoia in 1786 was the "high-water mark of the attempt to implement such [Gallican] policies."

The late Jesuit Fr. John O'Malley is pictured in a 2018 photo (CNS/Cindy Wooden)

The subsequent outbreak of the French Revolution gave monarchs a new appreciation for the dangers of reform, and "only in 1794, eight years after the synod, did Pope Pius VI dare to issue a bull, Auctorem Fidei, that condemned eighty-five of the synod's proposals. The governments of Austria, Tuscany, Naples, Turin, Venice, Milan, Spain and Portugal refused to publish the bull, a striking indication of the level to which papal authority had sunk."

O'Malley's treatment of the theological ferment between Vatican I and II, equally attentive to the interplay of theological ideas and practical, often political realities, gives way to the second chapter from one of the volume's editors, Villanova theologian Massimo Faggioli. "The Catholic Church in the period between Vatican I and Vatican II makes a transition from Christendom to what philosopher Charles Taylor calls the 'age of mobilization,' in which religion is no longer 'a community mentalité, but a partisan stance.' " The loss of papal temporal power, and the defeat of the theology that supported it, "was also translated into a magisterial response to the challenges of social and political modernity."

This is key: Even the most conservative and reactionary of pontificates were responding to modernity. There is no escapism from history, which is partly why "the reception of historical thinking by the theology of Vatican II" becomes necessary.

Advertisement

Faggioli keenly analyzes the way the catastrophic wars of the 20th century affected Catholic theology and the church's pastors. He notes, also, that post-World War II migration from Catholic countries and cultures to mixed or largely Protestant ones, had this result: "religion ceased to be associated primarily with specific denominations and denominational creeds and came to be associated with broad ethical and political trends along 'liberal' and 'conservative' political lines." The Catholic faith, so long carried by the culture, became more notional, more propositional, with increased polarization then becoming an inevitable outcome.

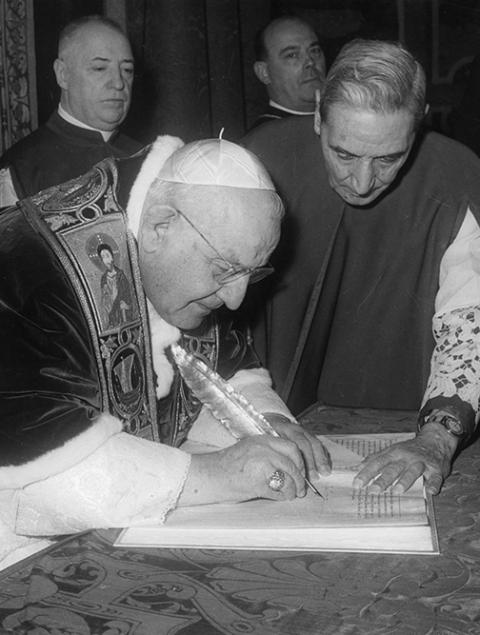

Pope John XXIII signs the bull convoking the Second Vatican Council Dec. 25, 1961. (CNS)

Perhaps Faggioli's strongest argument comes against those critics of Vatican II who claim it was responsible for the crisis of Catholicism in our time. "This view of the relationship between Vatican II and contemporary Catholicism is not only anti-historical; it is also the product of an exclusive focus on the Western Catholic Church, whose only challenge was supposed to be, according to those critics, secularization and the marginalization of Christian morality and culture. This is a short-sighted way to understand the historical context in which Vatican II was conceived, prepared, and celebrated."

O'Malley and Faggioli do not suggest that the various post-conciliar debates are resolved by understanding the historical context in which the council took place. There will always be a place for more conservative and more liberal readings of Vatican II. Those who see the event primarily through the lens of aggiornamento or "bringing up to date" of which Pope John XXIII spoke will also likely highlight the "signs of the times" as a locus theologicus introduced by Gaudium et Spes. Those who lean into the ressourcement or "returning to the sources" theology that shaped the conciliar texts might be more inclined to emphasize the ecclesiology of communion.

What these introductory chapters make impossible, however, is for anyone to ignore either pole entirely, to ignore the fact that both poles exist and both shaped the council and must, therefore, shape its reception. These chapters, and indeed the entire volume, are an antidote to sectarian and extreme caricatures of Vatican II and the theology it inspired. If this text accomplished nothing else, that would be an enormous contribution.

The faithful attend a candlelight vigil in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Oct. 11, 2012, to mark the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The next chapter, by University of Edinburgh theologian David Grumett, explains how the ressourcement theology of the pre-conciliar era provided the council fathers with an alternative to the stale Roman theology that shaped the preparatory documents. Jesuit theologians like Henri de Lubac and Jean Daniélou "desired to unsettle the increasingly entrenched neo-scholastic Thomism by showing that it did not, as was claimed, constitute an objective synthesis of all prior theology."

That was not all. Their theological probing was likewise directed at taking the air out of some liberal theological balloons, Grumett explains. "Simultaneously, they wanted to contest liberal theological methodologies that bypassed historical sources altogether." This work dovetailed with that of the Dominican Marie-Dominique Chenu, whose work looked to Thomas Aquinas, not the early church fathers, but was aimed at "correcting neo-scholastic misconstruals of Aquinas." His student, Yves Congar, would likewise play an enormous role in shaping the conciliar texts.

Grumett goes on to not only examine the ideas drawn from the return to the sources, he actually details the various citations in the conciliar texts. Grumett notes that the draft text De Ecclesia contained only 35 patristic citations, compared with 500 references to magisterial teaching. The eventual text, Lumen Gentium, contained 78 references to Latin Fathers and 80 to Greek Fathers, and an additional 27 to medieval Latin texts. He notes that Augustine was the most frequently cited Latin Father, appearing 50 times in conciliar documents, 19 of which are in Lumen Gentium. St. Ignatius of Antioch is cited 11 times in Lumen Gentium ("In contrast with Augustine, who is frequently cited in support of the equal dignity of all Church members, Ignatius is thus deployed to endorse more traditional elements of Lumen Gentium's ecclesiology."), and another seven times in other council documents. Grumett concludes, "In summary, without ressourcement, Lumen Gentium could not have been written." He goes on to analyze the patristic references in every conciliar text.

Pope Paul VI makes his way past bishops during a session of the Second Vatican Council in 1964. Vatican II, in its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium) promulgated by Blessed Paul VI on Nov. 21, 1964, presents succinctly the church's teaching on the role of the laity in the church and in the world. (CNS file photo)

German theologian Peter Hünermann has a dense but important essay on what he argues is the "qualitative uniqueness" of Vatican II, as it shifts from pre-modern ontological categories defended by the Roman and curial theologians to post-Kantian transcendental theologies, informed by historical consciousness. Here, John Henry Newman and the early 19th-century theologians of Tübingen loom large. He notes the importance of the council starting with the decree on liturgy, the one preparatory document that was constructed with these more modern ideas. "The epistemological presuppositions of Vatican II are no longer those that characterized the definitions of Vatican I," he writes. The redefinition wrought at Vatican II is this: "In conceptual terms, it means that God's plan of salvation — that is to say, God's self-disclosure — is (from a human perspective) the transcendental and also transcendent ground of all human capacity: of our freedom, our reason, our will, our loving, believing, and hoping — our selfhood." Whatever particular debates occurred at the council, Hünermann contends, this issue was present and up for debate.

The section on "Context and Sources" is rounded out with interesting, sometimes fascinating, chapters on issues that are important, if less central, than the first three. Jesuit theologian Norman Tanner writes about the various editions of the conciliar texts in English. Spoiler alert: Translators wield enormous power.

Italian historian Piero Doria has a chapter on the efforts to assemble the archive for Vatican II at the Vatican, as well as other key centers, and historian Federico Ruozzi has a really interesting chapter on other sources for the study of Vatican II, from diaries to journalistic accounts and even mass media accounts. The latter makes the important point that "television did not simply act as a window on the conciliar events; it played a significant role as a true agent of history, a real protagonist of the conciliar history, and on different levels."

At this point in the book, you have forgotten this is, essentially, a reference book. You have started to breathe the same air as the council fathers as they made their way into St. Peter's Basilica on Oct. 11, 1962, for the opening of the council. The sociocultural parameters have been set and the intellectual issues set forth. You can start delving into the drafting, debates, editing and final enactment of the various conciliar documents. This volume turns, next, to those individual documents and so shall we when we conclude this review on Monday.