(Unsplash/Aiden Craver)

Mason Freeman recalled how he'd stood with tears in his eyes as the president of an Illinois Catholic high school, an Augustinian priest, accepted him as a transgender student.

"He told me I was valued," Freeman told NCR. "It was the first time someone at school really listened to me, saw me."

The preceding years had been especially painful. At his Catholic middle school, LGBTQ people were "described as evil," said Freeman. Before transitioning, he'd felt suicidal and spent time in a psychiatric hospital.

"I became physically ill and severely depressed at not being seen as my true self," said the teen, now 18.

In high school, though supported by the administration, he spent most of his four years anxious a classmate might discover he was trans and he'd be tormented.

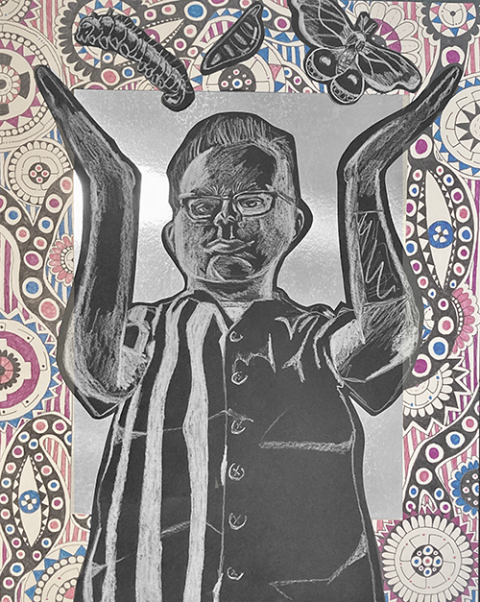

Mason Freeman, who is transgender, poses for a senior photo earlier this year. Many diocesan policies on gender identity and sexual orientation prohibit students from being openly transgender. (Courtesy of Mason Freeman)

Freeman's experiences reflect nationwide realities. As LGBTQ high schoolers confront serious and complex challenges — including higher rates of depression and suicide than their peers — U.S. Catholic high schools offer a range of welcome and rejection.

LGBTQ advocates say many Catholic secondary schools are working hard to support students. But they also believe there's a particularly harmful trend: LGBTQ youths face a growing number of diocesan-approved policies or guidelines on gender identity and sexual orientation. According to critics, the newest are among the harshest.

This summer new or updated written policies were released by the dioceses of Green Bay, Wisconsin; Lafayette, Louisiana; Memphis, Tennessee; Sioux Falls, South Dakota*; and the Archdiocese of Omaha, Nebraska.

"Catholic high schools struggle with how to minister to LGBTQ teens because in the background is the specter of these policies," said David Palmieri, a theology teacher at Xaverian Brothers High School in Westwood, Massachusetts, who holds a master's in theological studies from Harvard Divinity School. Palmieri has conducted extensive research on the policies and created a public folder containing copies of most.

"There is a disconnect between the legalism of many policies and the lived experiences of the human person," said Palmieri. "They are not creating schools of encounter. They help create a culture of fear."

'Source of despair'

Across the country at least 30 dioceses have policies addressing gender identity, and — to a lesser extent — sexual orientation. Many cover all diocesan institutions but some focus solely on schools.

While they exist in only an estimated 15% of U.S. dioceses, "the fear of them affects people broadly," said Marianne Duddy-Burke, executive director of DignityUSA, a Massachusetts-based advocacy organization for LGBTQ Catholics.

"We get calls from Catholic school parents all over the country who have heard about a policy that they know would be harmful to their kid. They ask, 'Could it be coming here?' "

In addition to the five new policies this summer, a minimum of four dioceses — among them the archdioceses of Boston and Portland, Oregon — are in "various stages of discussing documents," according to Palmieri.

The policies or directives frequently share similar language, format and content. They begin by critiquing the culture's acceptance of "gender ideology" and/or feature a mini-catechesis on gender identity and sexuality. The tone often is pastoral, emphasizing compassion and the need to protect LGBTQ youths from "unjust discrimination" and bullying. Then they move into the policies.

Advertisement

Jesuit Fr. James Martin, a longtime advocate for LGBTQ youths and their families, described the policies as "often draconian" and "heavily relying on the language of sin."

For LGBTQ Catholics "who just want to feel welcome in their own schools and parishes, many of these directives are the source of despair," said Martin.

The document issued by the Sioux Falls Diocese, led by Bishop Donald DeGrood, admits it is "intentionally exclusionary," and, like the one from Marquette, Michigan, places limits on who can receive the sacraments.

Individuals who "live a transgender lifestyle" may not receive Communion or be confirmed "until they fully accept the teachings of the Church," reads the Sioux Falls policy.

By admitting it is "intentionally exclusionary," the policy introduces its own form of scandal by putting limits on Christ's love for the marginalized, said Palmieri. In addition, the use of "transgender lifestyle" multiple times in the document "is a pejorative choice that unfairly groups transgender persons as one kind of person."

"There is a pluriform actualization of our humanity, which plays out in ways that cannot be categorized by a single sweeping reference to 'lifestyle,' " Palmieri said.

The Diocese of Wichita, Kansas, reflecting wording of numerous policies, says "Schools shall consider the gender of all students as being consistent with their biological sex, including, but not limited to, the following: participation in school athletics; school-sponsored dances; dress and uniform policies; the use of … locker rooms, and bathrooms; titles, names, and pronouns."

Roy Petitfils, a Louisiana-based Catholic author and counselor who's worked with young people for more than 25 years, said denying a requested name is unnecessarily harmful.

"The No. 1 thing schools can do to support transgender youths is to give faculty permission to call students by their chosen name and pronoun," Petitfils said.

A 2018 study suggests that when transgender teens are called by the name they believe aligns with their gender identity, it reduces depressive symptoms and overall suicidal risk by as much as 56%.

Non-diocesan institutions administered by religious orders tend to have more independence in how they minister to LGBTQ students, regardless of a policy. The Augustinian-run high school that enrolled Freeman as a transgender student is in the Diocese of Joliet, Illinois, whose policy states diocesan schools "will interact with students according to their biological sex as based upon physical differences at birth."

Freeman said he's worried about students who must contend with such a policy. He said without the welcome he encountered from his high school administration, "I'm not sure if I would be alive today."

Approved in August, the initial Omaha policy is being revised after Archbishop George Lucas received feedback, some of it critical, from local school communities. Archdiocesan staff said the wording will change but the content will not.

Worried about harassment, Mason Freeman kept his gender identity to himself for most of high school. But his senior year he chose to depict his transition journey in his Advanced Placement art class. "I got a little risky at the end," said Freeman, "I thought, 'I've been hiding who I am for so long, I want to share because maybe it will change people's position on transgender individuals.' " (Courtesy of Mason Freeman)

In the original copy's section on social media use, it said students must not "promote, advocate, or endorse a view or conduct contrary to the Catholic Church's teachings, including on human sexuality. … A student who violates these standards may be disciplined, up to and including dismissal."

Social media is where many teens, especially queer teens, find acceptance and encouragement —"essential to their mental health," Petitfils said. "This essentially closes that developmental avenue and forces these youth into greater isolation."

Tim Uhl is superintendent of Catholic schools for the Diocese of Buffalo, New York, and previously served as a lay consultant to the U.S. bishops' education committee. He said sexual orientation and gender identity are different realities with unique challenges, but they are at times conflated in policies in problematic ways.

Just as students are told they cannot express a gender other than their "biological sex," they cannot express their same-sex sexual orientation.

The Diocese of Corpus Christi, Texas, policy reads: "Expressions of a student's disordered inclination for same-sex attraction are prohibited as they may cause disruption or confusion regarding the Church’s teaching on human sexuality."

Uhl points out there should be no expression of sexual affection toward anyone at school, and there are no equivalent policies addressing heterosexual behavior.

"And the policies indicate you can be expelled if you make a mistake," said Uhl. "It has a chilling effect on students."

The Sioux Falls policy bans students from supporting civil rights for individuals in civil unions. It states that "advocating for civil unions between individuals of the same sex and/or civil rights to be granted … shall be considered equivalent to advocating for individuals experiencing same-sex attraction" and is prohibited.

Policies do not prevent students with gender dysphoria or same-sex attraction from enrolling, but a number of them, to varying degrees, tie enrollment and employment status to policy compliance.

Such policies send the message that "the worship of the law is valued more than human persons," said Palmieri. "Jesus warned against that."

Youths at risk

Two years ago, a student at Xaverian Brothers High School asked Palmieri if he could speak with him privately.

The teen first shared how as a gay male he'd felt a relentless sense of otherness and isolation at school and how he'd ultimately lost his self-respect.

"Then, his voice quivering, this student told me he'd tried to kill himself," Palmieri told NCR. "It was a powerful moment, an experience that made me say to myself, 'Something has to be done.' "

According to a 2022 national survey by The Trevor Project, an organization providing crisis support to LGBTQ young people, nearly half of LGBTQ youths ages 13-24 seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year.

For transgender and nonbinary youths, the figures are even more distressing, with nearly 1 in 5 attempting suicide. Youths of color reported higher rates than their white peers.

David Palmieri founded a network of Catholic school educators who accompany LGBTQ students. (Courtesy of David Palmieri)

Driven in part by these figures and the knowledge the Xaverian Brothers student's experience was shared by others, Palmieri has for the past few years conducted research on supporting LGBTQ students in Catholic schools.

Early on he found there was ample fear — in large part because of the diocesan policies — and few resources to help educators support LGBTQ students. There are some, such as the new website Outreach and materials through New Ways Ministry and the Marianist Social Justice Collaborative. Overall, though, it's "a desert landscape," said Palmieri.

To help fill the void, he formed a grassroots network of Catholic secondary educators. Called "Without Exception," it now comprises around 250 people committed to discerning "the art of accompaniment."

"We are not a secret group looking for the bishops to dismantle church teaching," Palmieri said. "We are educators in Catholic high schools whose primary responsibility is to children and how we can be faithfully Catholic but also meet the needs of kids. It's a really narrow ridge between apologetics and pastoral ministry, and it's hard to do."

Palmieri said Catholic leaders need to take seriously the data that shows a correlation between unwelcoming environments for LGBTQ teens and poor life outcomes, including increased risk of suicide.

"There is not a direct causal link between diocesan policies and these outcomes," said Palmieri. "However, we would be foolish not to recognize the inhospitable tenor of these policies as a contributing factor to young people feeling unwelcome in formative places like home, school and church."

Behind the policies

A bulk of the diocesan policies were issued after the Vatican's Congregation (now Dicastery) for Catholic Education in 2019 released "Male and Female He Created Them" — a document addressing "gender ideology" and Catholic education — and many draw from its language.

Praised by some, the Vatican document also received criticism for its contents and the fact that no LGBTQ people were consulted directly — a failure congregation prefect Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi admitted.

More comprehensive and authoritative texts related to transgender individuals were expected to follow soon after from the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, but no documents have been issued yet.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church describes homosexual acts as "intrinsically disordered" as well as "acts of grave depravity." It also says that men and women with same-sex attraction "must be accepted with respect, compassion and sensitivity."

But there currently is no such official magisterial teaching on transgender individuals, explained Ish Ruiz, a postdoctoral fellow at Emory University in Atlanta. Ruiz has a doctorate in ethics and theology and offers support to Catholic school educators ministering to LGBTQ youths.

Ish Ruiz is a postdoctoral fellow at Emory University in Atlanta and offers support to Catholic educators ministering to LGBTQ teens. The Catholic Church's teachings on sexuality and gender are not uncontested, said Ruiz, and Catholic doctrine develops in light of new information in psychology, sociology and biology. (Courtesy of Ish Ruiz)

Instead what the church teaches about transgender people draws from several less authoritative sources, according to Ruiz, including Pope John Paul II's "theology of the body," "Male and Female He Created Them" and Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis' 2016 encyclical letter on the pastoral care of families. It's also built on the Genesis passage "male and female he created them."

Based on these documents, many church leaders ultimately recognize a person's sex and gender as that assigned at birth — based on their genitalia, said Ruiz.

He said it's important to understand, however, that church teachings on LGBTQ individuals are not uncontested, and Catholic doctrine develops in light of new information in psychology, sociology and biology.

"Human sexuality and gender are incredibly complex, and absolute certainty in either direction is problematic," said Ruiz. "We need to be humble enough to know we don't know everything about this, and Catholic schools must teach students how to properly form their conscience by seriously considering the teachings of the church while also wrestling with different perspectives and overall uncertainty on these matters."

Sr. Luisa Derouen is a Dominican Sister of Peace who has ministered among the transgender community since the 1990s. She views the church's reliance on binary gender science as "extremely simplistic" and ignoring current scientific views.

"The Catholic Church teaches that the first 12 chapters are not historical and not science, yet many treat Genesis 1:27 ('male and female he created them') as though it were science," said Derouen.

In fact, she said, studies suggest sex is determined by a complex interplay between sex chromosomes, gonadal hormones, internal genitalia, external genitalia and gender identity, which some refer to as "brain sex."

"Policy positions that follow from the erroneous premise that transgender people don't exist are downright dangerous to the lives of trans people," said Derouen.

Sr. Luisa Derouen, right, with Scotty, who asserts, "I am of God and I have beauty in this world that can only be viewed by those who choose to see it." Read more at globalsistersreport.org/node/188029. (Provided photo)

Echoing reactions to "Male and Female He Created Them," LGBTQ advocates have criticized the diocesan policies for a lack of input from LGBTQ individuals.

NCR contacted all dioceses and archdioceses with known policies, asking who helped draft the documents and if any LGBTQ individuals were consulted. About one-third responded, and a handful of diocesan spokespeople said those who drafted the policies consulted individuals with same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria.

Bishop Michael Burbidge of the Diocese of Arlington, Virginia, "has personally spoken with many individuals who have same-sex attraction and gender dysphoria," Billy Atwell, diocesan chief communications officer, told NCR in an email.

Atwell said the purpose of Burbidge's "A Catechesis on the Human Person and Gender Ideology" was to "ensure that when assisting those with same-sex attraction or gender dysphoria, or defending our faith in the public square, we stand upon the divine and timeless teachings of the Church regarding what is true about the human person and human sexuality."

Fr. Philip Bochanski, executive director of Courage, a support ministry for gay Catholics focused on chaste living, told NCR he has offered pastoral feedback on two or three policies. And staff of the Person and Identity Project, or PIP, have also served as consultants, according to Ella Ramsay, Catholic studies program coordinator for PIP. It's unclear how many policies PIP — an initiative of the Catholic Women's Forum at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a conservative think tank — has assisted with; Ramsay told NCR PIP does not share details on consulting. She did confirm staff presented lectures and workshops related to gender identity in nearly a dozen dioceses last year.

Funded in part by Our Sunday Visitor Institute for Church Innovation, PIP aims to "assist the Catholic Church in promoting the Catholic vision of the human person and responding to the challenges of gender ideology." Co-founder and director Mary Hasson recently spoke at a Napa Institute event on "Liquid Gender and Its Consequences."

As Palmieri has pointed out, some dioceses also draw their perspectives from controversial medical sources, including the American College of Pediatricians. Classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, the group was founded in 2002 by socially conservative members who split from the American Academy of Pediatrics after the AAP endorsed adoption by same-sex couples.

Abigail Favale, a writer and professor at the McGrath Institute for Church Life at the University of Notre Dame and author of The Genesis of Gender, believes schools must work proactively to accompany and support gender-questioning youths while also "holding to a Catholic anthropology."

Favale said there's a mix of "good and bad policies," and she'd like to see less "sterile and harsh language" used in some. She also said policies attempting to "micromanage gender nonconformity" are problematic. "If all are drawn as a 'Barbie and Ken' kind of thing, that's ultimately not helpful and would be a nightmare to police. "

At the same time, Favale feels there's a lack of rigorous scientific evidence about gender-affirming care and that it's important to "clarify where boundaries are for students, parents and teachers, so everyone is clear what steps a school will take and not take."

"Educators need to keep in touch with what's real and true and good," she said.

Uhl thinks that instead of broad policies, situations should be addressed on a case-by-case basis and begin with the family. "The way to approach this is to listen, to come in with curiosity," he said. "You'll find often parents struggling themselves, asking themselves, 'Was I a good parent?' 'Did I do something wrong?' The first approach is to understand where the family is. It's a simple approach and a starting point."

There's much at stake when it comes to how LGBTQ teens are treated in Catholic high schools, said Petitfils. The policies can impact mental health in critical ways but also "students' ability to feel loved by God, because they identify God with their experience at Catholic schools."

If schools worked harder to find ways to listen to young people and "keep them at the table instead of saying what's wrong and disordered," Petitfils added, "our church would look more like a resurrected Christ than Christ mangled and crucified."

*This story has been updated to correct that the Diocese of Sioux Falls is in South Dakota.