Shanon Sterringer is seen alongside an image of St. Hildegard of Bingen at Hildegard Haus, the church community she leads as a Roman Catholic woman priest in Fairport Harbor, Ohio. (Don Clemmer)

Fairport Harbor, about 30 miles east of Cleveland on the shores of Lake Erie, has a naturally ecumenical flavor. The village covers 1 square mile and is home to some 3,000 people and nine churches.

The newest addition to the village's faith communities is Hildegard Haus, open since September, a community modeled on the spiritual vision of St. Hildegard of Bingen, the 12th-century German Benedictine abbess who was canonized and named a doctor of the church in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI.

The Community of St. Hildegard is led by Shanon Sterringer, a woman beloved to many village residents due to her decades working in ministry at Fairport Harbor's Catholic parish, St. Anthony of Padua. Sterringer opened Hildegard Haus as the Hildegarden, a nondenominational retreat center in 2016, after purchasing the property from the Byzantine Catholic Church, which had closed the parish there in 2012.

Her work to transform that rundown building into a center for the whole community contributed to her being named Fairport Harbor's Citizen of the Year in February 2019. That honor came in the middle of a nine-month sabbatical Sterringer took after exiting her role at St. Anthony, an interlude that culminated in her being ordained in Austria through the Association of Roman Catholic Women Priests.

The move prompted a Dec. 17 letter from Bishop Nelson Perez, then head of the Cleveland Diocese, urging her to respond by Jan. 3, at which point he would communicate her "refusal to reconcile" to the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Sterringer did not respond and openly admits she has effectively excommunicated herself under canon law.

"Most of us don't set out saying, 'I want to be excommunicated,' " said Sterringer, 47. "We're on the margins, really, and kind of outside of [the Catholic Church]. At the same time, I still see us as part of a bigger body — of Christ."

Shanon Sterringer celebrates the Eucharist at Hildegard Haus in Fairport Harbor, Ohio. (Rick Sterringer)

Sterringer's story offers an insight into where the church in the United States finds itself, at a time of transition marked by the vision of reform modeled by Pope Francis, which includes major questions about the role and dignity of women in the church. Sterringer's services at Hildegard Haus have drawn about 35 people on a given Sunday, more than a few of them from her former congregation at St. Anthony, which is visible just two blocks up the road.

Hildegard Haus has transformed the former Byzantine church, with the altar brought down from the sanctuary space and along one wall, with seating moving out from it in a semicircle. Depictions of St. Hildegard's art line the walls of the bright, repurposed space, which Sterringer's husband, Rick, helped to renovate.

On Sunday mornings, Sterringer leads a worship service modeled on Catholic Mass, but which is also a collaborative work in progress.

Journey in the church

"I'm not threatened by it," said Fr. Pete Mihalic, longtime pastor at St. Anthony and Sterringer's mentor, friend and godfather to her youngest daughter. "She was like an associate pastor here. I mean, she just did it all within the scope of what she was able to do and just transformed this place beautifully. The people love her very, very much."

Sterringer, who began in the parish as sacristan at age 25, extended the reach of her duties over 22 years at St. Anthony by pursuing various degrees and certifications. She recognizes now that she felt a call to ordination from the beginning and was "trying to do everything I was allowed to do and hoping that would fulfill my call."

This included a 2003 bachelor's in religious studies from Cleveland State University; a 2007 master's in theology from the diocese's St. Mary Seminary and Graduate School of Theology; a second master's degree from Ursuline College in 2011; a 2012 doctorate in ministry at St. Mary Seminary on women's leadership in the church; and a 2016 doctorate from Union Institute and University. She also received certification as a diocesan master catechist, lay ecclesial minister, eucharistic minister, lector, marriage preparation minister and procurator in annulments.

She notes that people have since said to her, "What did the diocese think you were going to do with that kind of education if you didn't have a call?"

Sterringer also participated in parish liturgies as fully as the church allows, wearing an alb as liturgist/master of ceremonies, to the point that people were used to seeing her at the altar. "Seeing a sanctuary that's not just full of men forms people," she noted. "There's always a desire first to bring about as much positive change as you can within the fold."

Sterringer took six months off during her studies for her first doctorate to give a look at the Episcopal Church. She recalled a decisive piece of advice from a mentor: "You need to discern if you're called to the Episcopal Church or if you're called to be Catholic in a new way."

Sterringer added, "In my heart, I'm a Catholic."

A sign adorns the garden outside of Hildegard Haus. (Don Clemmer)

As she tried to figure out how to be Catholic in a new way, she discovered St. Hildegard. "She gave me hope. Here's this strong woman who didn't mince her words when addressing clergy or injustices, clericalism, and yet here she is a doctor of the church," Sterringer said. "Based on what we know of history, it's shocking she wasn't burned on a pyre."

In purchasing and renovating the former Byzantine Catholic church building into the Hildegarden retreat center, Sterringer saw herself paving a way for future generations, by lifting up the power of Hildegard's charisms while knowing that she would never be ordained. She also saw it as an outlet for staying in a positive relationship "with an institution that's not there yet."

But as time wore on, Sterringer found something bigger kept throwing up roadblocks and pushing her further out.

"I felt like I was suffocating. I felt like I just wasn't being who I was called to be," she said of her last year at the parish.

Her work and ministry fell away, piece by piece. Conflicts with the diocese left her crying, feeling like she wasn't living her vocation with integrity. The decisive moment came for her in August 2018, the night before she was to give the diocesan pastoral ministry retreat, when she learned that a friend, the bishop of Cuddapah, India, had been accused of misappropriating diocesan money to fund a luxurious double life with a wife and son.

"That just devastated me," she said, noting that the sense of betrayal led her to realize, "I have nothing else to give here."

When St. Anthony faced a budget shortfall the following year, she told her pastor to solve the deficit by eliminating her job. She recalls telling him, "I think God is calling me somewhere else."

Her job ended in September 2018, leading to her sabbatical, a period of spiritual darkness and, ultimately, her decision to move forward with ordination.

"I didn't want this place to be a zoo. I thought, that's not what it's about," she says. Donations have included custom furnishing, banners, statues and other artwork.

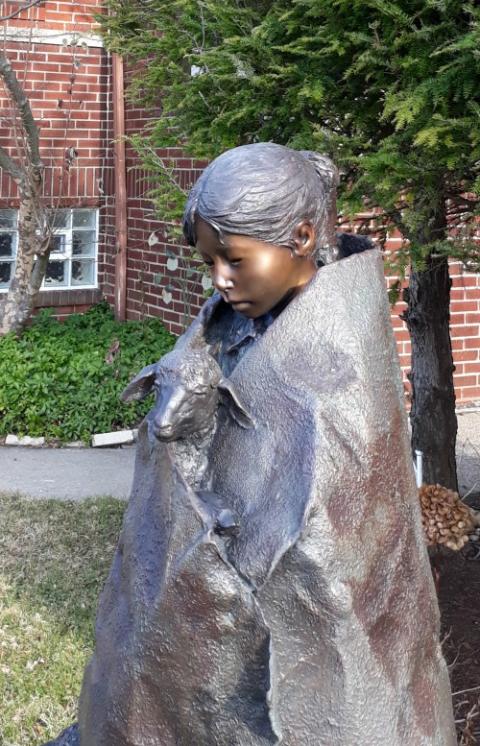

The statue "Shepherd Girl" by Dee Toscano was donated to the Hildegarden in 2018. (Don Clemmer)

"It's been nothing but positive," Sterringer's husband, Rick, said of the reaction from the community. Shanon affirmed that support comes from unlikely types, such as older people who've stuck with the church all along.

"It's been a rollercoaster ride, that's for sure," Rick said of the experience of accompanying his wife through the discernment of her path.

Weathering COVID-19

Despite the community's newness and small size, the COVID-pandemic hasn't been deleterious to Hildegard Haus.

"When this pandemic first hit, I was very concerned," said Sterringer. "It has really been enriching in a way I did not expect."

Taking their community online, Sterringer has found that the numbers of people signing on for weekly vespers, Bible study and rosary are triple the church's live congregation. The same goes for Sunday liturgies.

"Our weekly numbers have increased; collections have remained steady," Sterringer said, adding that shortly after the community went into stay-at-home mode, they received an unexpected donation to help provide the resources they need "to weather this storm and secure our future."

She likens her experience to how early church communities were formed, but now with Wi-Fi and electronic devices.

She has retained a good relationship with the local Catholic parish.

"Initially, she saw [Hildegard Haus] almost as a halfway house for disenfranchised Catholics to come home, but there's so many from my experience," says Sterringer's former boss, Mihalic. "People are leaving. You don't always have a context, an atmosphere in which to deal with that. She has that context, and they feel welcome there. And she can talk on that level with them."

"We have a lot of people looking for healing," said Mary Rininger, a former St. Anthony parishioner who attends Hildegard Haus with her husband, David. "They have been so hurt by the structured churches in their life, and not just the Catholic Church."

"The church broke my heart" says Marty Hillyer, chair of the Hildegard Haus board, who says the abuse crisis first drove him away before Sterringer brought him back to church in 2017. "I really feel the love of God through her. ... She is the poster child of what a priest should be."

Patricia and Morgan Spiker, a couple from St. Anthony who've been married for 43 years, began attending Hildegard Haus in addition to St. Anthony as a way of supporting Sterringer. But Patricia notes, "We just fell in love with here. This is a wonderful place," adding that it's not unusual to find themselves talking about Shanon's homily "all afternoon."

Patricia and Morgan Spiker at Hildegard Haus in Fairport Harbor, Ohio (Don Clemmer)

"Her message, her homilies, have been phenomenal," says Tim Kalista, a former priest of the Cleveland Diocese. "She's trying to balance inclusivity with tradition."

The "crime" of women priests is regarded as worse than sexual abuse in terms of the way it has to be resolved under canon law, Sterringer noted. "And I think most of the people sitting in the pew, whether they agree with women's ordination or not," and with friends and family attending denominations that ordain women, are asking themselves, "How can it be worse than a child being raped by a priest?"

This leads to a discordance people sense at a gut level, she says.

Approaches to reform

One curiosity of the timing of Sterringer's move is that it comes nearly seven years into the pontificate of Francis, who is widely viewed as a reformer and who has even, for the last several years, sponsored commissions to explore the question of opening the diaconate up to women, even as he's stated that he sees Pope John Paul II's ban on ordaining women priests as forever binding.

"I think Francis introduces hope," Sterringer said. She cited his recent comments that he isn't afraid of schisms and noted that the change she hopes to affect runs deeper than the single issue of women's ordination.

"If tomorrow Pope Francis said, 'I'm ordaining women to every level of holy orders,' our problems aren't going to be resolved. They're actually probably going to be a nightmare. And it's probably going to be a war, really, because the respect isn't there between the sexes."

It's unusual for Roman Catholic women priests to have their own physical church structure. (Sterringer currently owns Hildegard Haus, but is in the process of transferring ownership to the community via its board.)

Advertisement

"A lot of the women priests tend to respond once they're retired," Sterringer said, because it's essentially a career-ending move. "One of the comments a friend of mine made ... is, 'You know, Shanon, you're unemployed and unemployable. All of your degrees, all of your credentials are through an institution that has now blacklisted you, in a sense.' " (Sterringer is still paying off student loans from her two doctorates.)

She has heard similar sentiments from her family. Her oldest daughter, 26, is no longer affiliated with any organized religion. "She was very supportive, but she said, 'Mom, why would you invest any more of yourself in the church? It's taken already so much from you, and it's just hurt you time and time again. Why would you give it anything else of yourself?' "

Mihalic credits his friend for how she's conducted herself on an otherwise fraught journey. "I think that's Shanon's biggest grace here is her transparency. She puts it on the line and says this is who I am, and this is how I feel God is calling me and, in a sense, take it or leave it."

"I resisted it for well over a decade," Sterringer said. "And when you finally get to that place when you know it's time, it's very heart-wrenching, because you know that there's going to be a lot of loss and lot of grief and a lot of broken relationships and changed relationships. And yet I think when you're at that place — 'I lost everything. What else do I have to lose at this point?' — that's where that liberating grace comes through."

[Don Clemmer is a writer, communications professional and former staffer of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He writes from Indiana and edits Cross Roads magazine for the Catholic Diocese of Lexington, Kentucky. Follow him on Twitter: @clemmer_don.]