Pauli Murray, left, then a New York lawyer, receives a Mademoiselle Merit award Dec. 30, 1946, as one of 10 young women selected by Mademoiselle magazine as "Young Women of the Year." (AP Photo/John Lent)

I thought I knew Pauli Murray, or at least knew something about her. Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, Rosalind Rosenberg's incredibly detailed and in-depth biography, reveals that I was wrong. No one, including many of her closest friends, knew Anna Pauline Murray (1910-85) in her fullness. Rosenberg has done the world an immense favor by presenting, in all its triumph and pathos, the life (or perhaps "lives" is more accurate) of this brilliant and defiant African-American.

Murray's life struck a resounding chord within me as one who has followed a rather similar path, at least in terms of becoming an attorney interested in issues of civil rights then finding myself called to the church and the life and work of a theologian. As a black woman with roots in the South, I understand and empathize with Murray's struggles to find a place where she could be free to be herself and her disappointments in confronting obstacle after obstacle because of her gender and race. She spent her life fighting against the harmful effects of these social constructs while also attempting to educate others and working to eradicate these forms of oppression.

Her experience as a woman of African descent fed her lifelong battle as an attorney, an activist and a priest to delegitimize laws that oppressed those with whom she identified. She refused to accept the restrictions society or the law placed upon her. In so doing, she broadened our knowledge of these issues by coining the term "Jane Crow" that brought out clearly the ways in which law and society discriminated against women, especially women of African descent, in much the same way that "Jim Crow" laws did against all people of color.

Rosenberg's biography also reveals that Murray suffered oppression as a sexual minority, believing for much of her adult life that she was a man trapped inside of a woman's body. Murray spent years arguing with medical doctors about her condition to no avail. Today, she would likely have identified as transgender, but language and science had not evolved sufficiently at that time to allow her to name her experience.

Raised in Durham, North Carolina, and orphaned before she entered her teens, Murray learned to negotiate life as a "boy-girl," as her adoptive aunt called her. She was lovingly raised by her two aunts, Sallie and Pauline (after whom she was named), and her maternal grandparents who took great pride in their Cherokee, African and Irish heritage. The South chafed Murray's sense of self, and she sought a greater freedom in the North. At Hunter College, Murray embarked on the first leg of what was to be a lifelong journey of self-discovery and dedication to the cause of civil rights, especially those concerning gender, race and class.

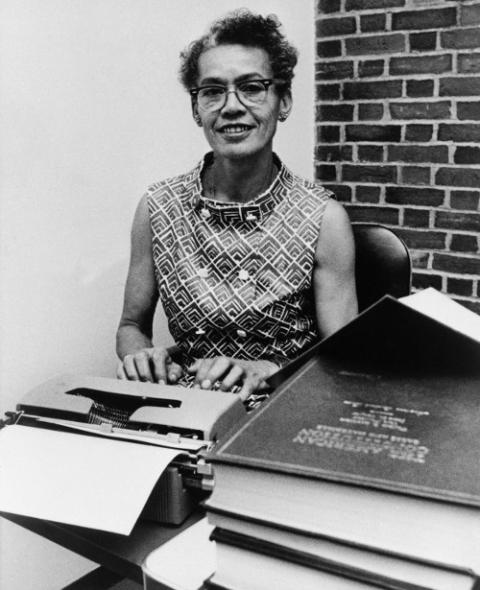

Brandeis University Professor Pauli Murray in Waltham, Massachusetts, Sept. 25, 1970 (AP photo)

Though she lived in a particularly volatile time, with the renewed repression of blacks in the South and the limitations on women's ability to expand their horizons, Murray achieved first after first: She graduated first in her class at Howard Law School; she was the first African-American to earn a Doctorate of Juridical Science at Yale University; and she was the first African-American female ordained an Episcopal priest. In so doing, she made friendships and connections with leaders in labor, civil rights, education and law.

Her studies and her work brought her into contact with luminaries like Thurgood Marshall, who used her senior paper as a critical part of the argument for opposing segregation in Brown v. Board of Education; Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who used her research on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to successfully expand the rights of women; Betty Friedan, with whom she co-founded the National Organization for Women; and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, with whom she had a warm yet challenging friendship with for over 20 years.

Labor organizer, social activist, journalist for the black press, poet, lawyer, teacher in Ghana, tenured professor at Brandeis, and Episcopal priest, Murray had a life full of achievement, but it was tainted by the constant repression she experienced based on her race, gender and sexual identity and also extensive periods of poverty that negatively affected her productivity and, at times, even threatened her life. She was a such stellar example of a Renaissance woman and excelled in so many worlds that, in 2012, the Episcopal Church proclaimed her a saint, a holy woman whose life was a model for all in the communion of saints.

Today, many of the issues that she championed have been recognized and affirmed. The crippling impact of race, class and gender on women of color was later termed the "multiplicative oppression" of women by Jacqueline Grant and other womanist scholars. More recently it has been termed "intersectionality" by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw. Today, as we proclaim Black Lives Matter, a movement founded by three young black women, two of whom identify as queer, we must recall Murray's persistent efforts to know and claim herself as male.

Advertisement

More than 30 years after her death, Murray is still a breaker of glass ceilings. In 2016, Yale announced that it would name one of its new residential colleges after her, the first woman and the first black person to be recognized in this way by the university.

Rosenberg writes:

She would have taken special delight had she lived to see her name engraved on a building at Yale University. … For Murray, who had championed "diversity" in all its forms, this honor would have felt like a vindication. In recognizing Murray in this way, Yale honored the decision she had made long ago to offer herself as a bridge, between black and white, male and female, northerner and southerner, left handed and right handed, old and young — an example of diversity in one body, on its way toward mutuality and reconciliation in a better world.

As a womanist, I would gladly claim Pauli Murray as a sister womanist, but I honor her own self-naming as a black feminist who refused to allow others to label her, restrain her or restrict her. Her life's journey was a roller coaster ride of highs and lows, great achievement and shattering disappointments, but through it all she maintained her faith in a God of love, justice, mercy and reconciliation — a God who fought alongside her to remedy the many wrongs of the world in which she lived, wrongs that still persist today.

[Diana L. Hayes is professor emerita of systematic theology at Georgetown University.]