During a Jan. 12, 2025, protest in San Salvador, El Salvador, Albertina Jovel Escobar holds a sign showing her son who was deported and sent to prison as soon as he landed in his home country. A group of Catholic mothers like Jovel warned that those deported to El Salvador could be sent straight to prison without due process, as the U.S. is in talks with the Salvadoran government about taking in deported migrants from different countries. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

As President Donald Trump moves to expel migrants unauthorized to be in the U.S., a group of Catholic Salvadoran mothers warn that deportees could suffer the same fate as their sons and daughters: sent to prison for months or years after being returned to the country.

The warnings come as a Jan. 26 report from CBS News says Trump is in talks with Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele to send men and women deported from the U.S. to El Salvador — even if they're not from there. That could mean an increase in deportees from countries such as Venezuela, which refuses to accept their deported citizens, and an increase in El Salvador's already crowded prison population.

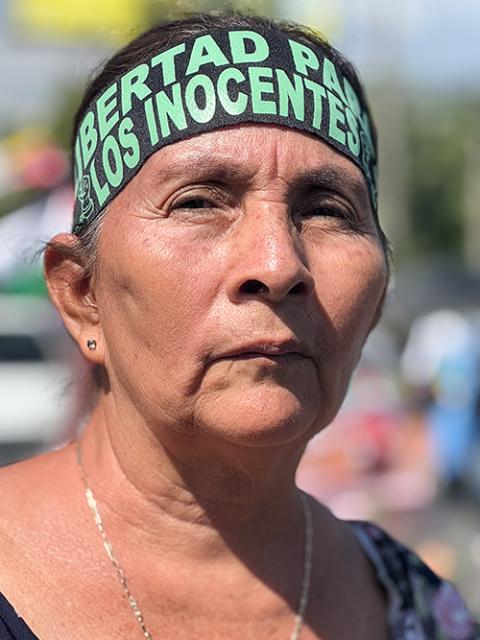

During a Jan. 12 protest in San Salvador, Albertina Jovel Escobar was part of a group of mothers waving photos and legal documents, telling stories of the fate of the deported.

"My son was deported Aug. 11, 2023, and as he was coming back from the U.S., he was arbitrarily captured [when he landed in El Salvador], even though he had no prior record." Jovel told National Catholic Reporter. "There was no reason for his capture."

Since then, the family hasn't heard from him and Salvadoran authorities won't say where he's being detained or why, she said.

In March 2022, the government implemented a crackdown called the "state of exception," saying it was to curb gang violence that had plagued El Salvador since the end of the country's civil war in 1992. The majority of Salvadorans say randomly detaining those suspected of being gang members or affiliated with them has made the country safer, but a consequence has been the incarceration of innocent people, along with the suspension of personal freedoms, including the right to legally defend oneself.

As El Salvador has been touting its safety, the U.S. is looking to send the deported to a "safe third country," allowing them to seek asylum there, according to the CBS News report.

Advertisement

But some like Leslie Schuld, director and co-founder of Center for Exchange and Solidarity in El Salvador, known as CIS, say El Salvador is not an ideal place to drop off those seeking refuge.

"The U.S is looking to deport migrants and refugees to El Salvador, a country with no jobs, no resources, overcrowded the size of Massachusetts, where they lock up and torture the poor. Shameful," she said.

The SHARE Foundation, an international nonprofit that works with solidarity projects in El Salvador, issued a statement at the start of 2025, saying, "It's entirely likely that there could be a direct line of deportation from the United States to the brutal [Salvadoran] penal centers."

Since the start of the crackdown, the Salvadoran government said it has detained more than 83,600 people, including some U.S. citizens and other foreigners. Mistakes have resulted in the detention of innocent people, but those are few, Félix Ulloa, the country's vice president, has said.

However few those wrongful detentions may be, human rights groups say that those mistakes have cost innocent people their lives, and that everyone has a right to a legal defense. But in the absence of the government listening, many like Jovel have taken to the streets to warn others.

"They were taken alive and we want them back alive," chanted the crowd of almost all women, almost all mothers, who took part in the Jan. 12 march opposing state of exception and other policies.

Jovel, like others, said she was surprised when she heard of her son's detention because he had hardly lived in the country and had no criminal record. In their rural town of Guancora, in northern El Salvador, the few jobs available are not enough to pay for one's living expenses, that's why he migrated, Jovel said. But she said she never imagined that migrating would one day lead him to a prison cell.

After landing, he managed to make one phone call to his sister to tell her what was happening.

"They told him they were detaining him while they investigated," Jovel said. "And until now, I don't know anything else."

Berta Alicia Aguilar de Durán said her son Ever Durán, too, had been working in the U.S., in New York, and following a psychotic episode, he was deported to El Salvador in May 2022. When his family went to pick him up at the airport, he was nowhere to be found.

Aguilar said she later discovered that he had been taken to prison by Salvadoran authorities who accused him of illicit association with gangs, even though he hadn't lived in the country for a long time and never belonged to a gang.

Her son has mental issues and he needs medicine, not prison, she told NCR as she took part in the demonstration. Others recounted similar tales, tugging at reporters to get the story of their loved ones out to the world.

In June 2024, a group of lawyers from Socorro Jurídico Humanitario (Humanitarian Legal Aid) in El Salvador told Salvadorans during a presentation in Washington of three cases they had seen at their offices involving deported men taken straight from El Salvador's airport to the country's prisons. Since then, they say they have seen a rise in those situations and told the Los Angeles Times in January that deportees now run a high risk of imprisonment once they touch Salvadoran soil.

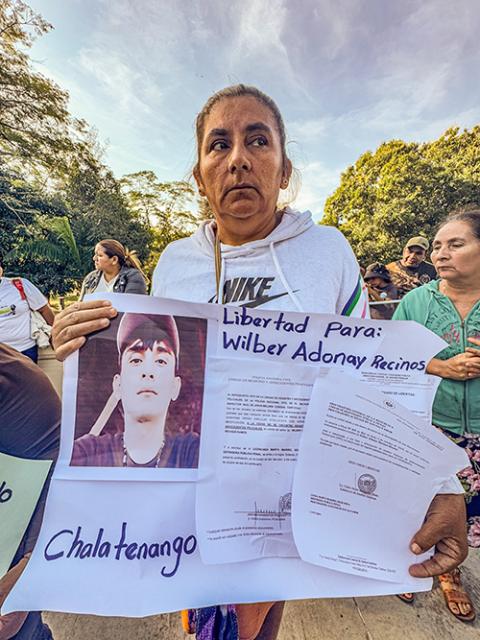

Although her son was not deported, María Estela Ramos, of Guarjila, El Salvador, said he's one of those who has been wrongfully detained by the government. She said the country's poor, with few economic resources, have no one to help them. Deportees, who arrive with the clothes on their back, also are easy targets, she said.

María Estela Ramos, of Guarjila, El Salvador, holds a sign Jan. 12, 2025, in downtown San Salvador, showing documents that show her son has no criminal record. She says he has been wrongfully imprisoned by the Salvadoran government. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Her son worked in agriculture, she said, and made the mistake of following the orders of officials who told him they were going to interview him in June 2022 and he would return home after they were done. Though he's never been charged with a crime, he has been detained for almost three years, she said.

Ramos, a Catholic, said the Salvadoran church has not been helpful in the plight of those wrongfully imprisoned, including the deported. Her parish priest told her they had been prohibited from getting involved. But another priest offered to write her a letter to vouch for her son's good character.

"So, I guess that's something," she said.

But by and large, they have been left alone to face the legal challenges and the ridicule of others, who along with accusing their children, accuse their mothers, too, of belonging to the gangs that made life hell for Salvadorans.

One of those who suffered that hell was Luis Sánchez, who unsuccessfully tried to rip a poster Dec. 30, 2024, from a group of women protesting the wrongful arrests near the Cathedral of San Salvador. The women wanted Salvadorans who are living abroad and were visiting for the Christmas holidays to hear about their plight.

"They're all gang members," Sánchez said, showing what had happened to him at the hands of gangs. They cut two fingers from his left hand and put a knife to his face, something that would regularly happen before the state of exception, he said.

The group said they agreed with him that criminals should be behind bars but begged him to consider the plight of those who haven't committed crimes, particularly those being punished for migrating.

The SHARE Foundation said the way the Salvadoran government sees it: "The alleged criminal charge was that, if someone has been deported, they are inherently a criminal."

And as the country's Bukele draws closer to Trump, the threat of mass incarcerations of those deported seems more of a reality, SHARE said.

This week Secretary of State Marco Rubio is set to make a stop in El Salvador during his first diplomatic overseas trip, which is expected to focus on curbing immigration and on economic issues.