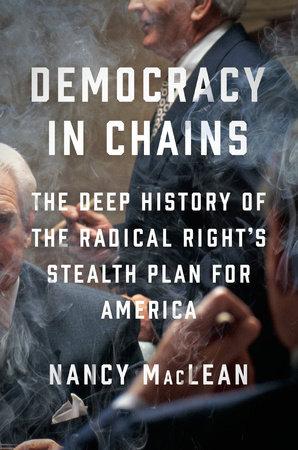

James McGill Buchanan's career as the intellectual godfather of libertarianism starts at the University of Virginia in the mid-1950s. (Dreamstime/Prazis)

When a review copy of Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America arrived, the title put me off. I am not much of a fan of conspiracy theories. But, then I noticed that the author, Nancy MacLean, is a historian at Duke University, not a tabloid writer. And, as she explained in the introduction, she had the kind of experience every historian dreams about: discovering materials of enormous significance that no one had bothered to archive.

MacLean's find concerned the papers of James Buchanan, which remained in his old office at George Mason University, the school where Buchanan closed out his career. Despite winning a Nobel Prize for his work on public choice theory, the economist is not a household name. But, as MacLean demonstrates, he provided the intellectual framework that the growing libertarian movement, and especially its leader Charles Koch, needed to pursue their goal of radically changing the political economy of the United States.

Buchanan's career as the intellectual godfather of libertarianism starts at the University of Virginia in the mid-1950s, where he had been hired to lead the school's economics department. The university's president, Colgate Darden, was paralyzed by both the prospect of implementing Brown v. Board of Education and the prospect of "massive resistance" some in the state were calling for. Like most Virginians of influence — and Darden had served as governor of the Commonwealth — he was affiliated with the political regime of Sen. Harry Byrd, a convinced segregationist, and both the senator and the university president wanted to preserve the gentlemanly image Virginia had forged for itself.

Buchanan proposed starting a center for the study of political economy and social philosophy at the University of Virginia that would pursue, in an appropriately academic way, a means "to defeat the 'perverted form' of liberalism that sought to destroy their way of life, 'a social order' as he described it, 'built on individual liberty,' a term with its own coded meaning but one that Darden would surely understand." The center would train a new generation of thinkers to see what Buchanan saw in Brown v. Board: not a step towards fulfilling the nation's founding ideals, not the rectifying of a glaring social injustice, but mere government coercion.

It is obvious that Buchanan and his colleagues at the newly formed Thomas Jefferson Center failed to stem the tide of desegregation. But he did succeed in setting forth a vision of a society in which property rights were paramount, and "individual liberty" was locked in a zero-sum struggle with government power at all times. "To Buchanan," MacLean writes, "what others described as taxation to advance social justice or the common good was nothing more than a modern version of mob attempts to take by force what the takers had no moral right to: the fruits of another person's efforts. In his mind, to protect wealth was to protect the individual against a form of legally sanctioned gangsterism." It goes without saying that this is not the Catholic view of government. Just this past Sunday, Pope Francis spoke about the common good as the proper end of governance.

DEMOCRACY IN CHAINS by Nancy MacLean, published by Viking, 368 pages, $28

Buchanan, like Byrd, took much of his inspiration from John Calhoun, the fiery antebellum senator who had championed states' rights. He was not alone: Another seminal libertarian thinker, Murray Rothbard, was also explicit about his debt to Calhoun. What mattered was not the racial injustice black people suffered, but the attack on property rights, first against the slaveholders and now against the wealthy, forced to pay taxes for programs from which they did not benefit. In this worldview, racist consequences are perfectly acceptable so long as property is not unduly burdened. You would think it was the slaveholder who was at the receiving end of the lash and that the oppression black Americans suffered under Jim Crow was as nothing compared to the suffering, so-called, of those whose economic freedom was constricted by desegregation. Perhaps most frighteningly, Buchanan (and Rothbard) did not betray any overt racism: Their ideology simply trumped normal human decency, making them incapable of moral evaluation.

Another key inspiration for Buchanan performed a similar distorting role in shaping his ideology: his membership in the Mont Pelerin Society, a group that was devoted to the Austrian school of economics and named for the town in Switzerland where they met. Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek were the two most prominent minds among the Austrians. "F.A. Hayek had been worrying since the early 1930s about the growing appeal of social democracy in particular," MacLean writes. "He was concerned about the model of government that so many organized citizens of Europe and the United States were seeking, based on labor unionism, a welfare state, and government intervention for economic security." I say "distorting" because of all the things to be worried about in the early 1930s, surely the rise of social democracy was not the most troubling thing in the political landscape. Hayek's Road to Serfdom, published in 1944, became a hit in the U.S. after Reader's Digest ran excerpts, which is strange: Whatever path America was on then, still less today, it was not, and is not, a road to serfdom.

Buchanan's academic rise happened at a time when many economists were focused on market failure: The legacy of the Great Depression remained vivid in people's memory. Buchanan, like all notable entrepreneurs, looked in the other direction, at failures of government. "Where his interest and genius lay — even if you call it an evil genius — was in his intuitive grasp of the importance of trust in political life," MacLean writes. "If only one could break down the trust that now existed between governed and governing, even those who supported liberal objectives would lose confidence in government solutions." This was the late '40s. It would be hard to discern a more dominant theme of American political life in the last decades of the century than the loss of confidence in government. This did not just happen; it was helped along by Buchanan and his ilk.

Advertisement

Academics do not normally exercise a profound influence in a society as historically anti-intellectual as that of the United States. But Buchanan was no mere academic, and his cause attracted the kind of assistance that would extend his reach far beyond the walls of his academic center in Charlottesville. The William Volker Fund was a source of money for the free marketeers at Buchanan's center and, later, conservative foundations like the Scaife Family Charitable Trusts would support the efforts to reshape democracy.

Working with his colleague Gordon Tullock, Buchanan produced the book The Calculus of Consent and it argued that "allocating resources by majority decision-making invited voters to group together as 'special interests' — or 'pressure groups' — in collective pursuit of 'profits' (later called 'rent-seeking') from government programs. In turn, candidates for office felt obligated to appeal to these special interests to achieve their own goal of winning elections, so they promised gains to multiple constituencies." Buchanan and Tullock did not admit the possibility that politicians — or voters — might pursue a certain set of policies because they thought they were the right thing to do. All was craven self-interest. The funders guaranteed a wide circulation for the book that described the theory for which Buchanan would be most known — public choice theory. The fact that these economists did not focus on the typical concerns of economists, but instead on nonmarket decision-making, helped them stand out from the crowd. Backed by virtually endless funds, their critiques had the makings of a campaign and, in 1964, Barry Goldwater brought their ideas into the heart of the Republican Party.

Goldwater's defeat did not cause Buchanan or his confreres to lose hope. Revolutions take time. They also take determination, and soon Buchanan was to meet a man who had plenty of determination, as well as the deepest pockets available: Charles Koch. And the alliance the two forged would create the "stealth plan" MacLean highlights.

I shall conclude this review on Friday. (See: 'Democracy in Chains' book review, part two.)

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest! Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we will notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.