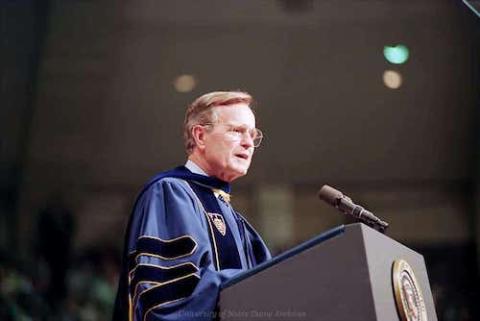

Joe Biden as U.S. vice president delivers an address after receiving the Laetare Medal during the University of Notre Dame's commencement ceremony May 15, 2016, at Notre Dame Stadium in Indiana. (CNS/University of Notre Dame/Barbara Johnston)

Inside the Joyce Center, the band played "Hail to the Chief." Outside, protesters said, "Hell, no!"

Such was the scene the last time a sitting U.S. president came to the University of Notre Dame, America's flagship Catholic university, which enjoys the distinction of hosting more presidential visits for commencement than any institution of higher learning other than the military academies.

Six U.S. presidents have spoken at Notre Dame's commencement exercises, and a total of nine presidents have received honorary degrees. Yet the decision to invite President Barack Obama to deliver a 2009 commencement address and receive an honorary degree proved to be a flashpoint, both for campus politics and the American Catholic Church.

Now, less than three months away from the 2021 commencement, a group aimed to "protect" the university's Catholic identity has launched a "Don't Invite Biden" campaign, while others are making their case that inviting the nation's second Catholic president is essential to the university's mission, setting up another likely showdown.

For now, the university remains tight lipped.

"Notre Dame doesn't discuss prospective commencement speakers until an invitation is proffered and accepted," Paul Browne, vice president of public affairs and communications, told NCR via email.

Yet in a January interview, Notre Dame's president, Holy Cross Fr. John Jenkins, acknowledged the possibility.

"I believe that we can and should welcome elected leaders to our campus, respect what is honorable in their lives and work, while we acknowledge where we disagree. Such an approach, I believe, is entirely consonant with the character of a Catholic university," he told the Catholic news site Crux.

"Whether Biden is invited or not, some will disagree and criticize our decisions, as they are entitled to do," Jenkins said. "My wish is only that we can avoid the vituperative character of such debates."

Advertisement

Obama at Notre Dame

Twelve years after Obama's appearance on campus, the spectre of the 2009 debate looms large.

Following the invitation of Obama, then-Bishop John D'Arcy of Fort Wayne–South Bend announced he would boycott commencement, saying the university had chosen "prestige over truth." D'Arcy was joined by more than 70 other bishops from around the country expressing their disapproval. Soon thereafter, Harvard law professor and former U.S. ambassador to the Vatican, Mary Ann Glendon, announced she would not accept the university's prestigious Laetare Medal, which would have been presented at commencement.

While ink was spilt over the controversy in the pages of national newspapers, on campus, student pro-life organizations opposed the invitation, and counter-protests were staged by more than 20 student groups that welcomed the decision. Those debates were offered a megaphone by national interest groups who joined the fray.

In the days leading up to the commencement, above the university's famed Golden Dome, a plane circled trailing banners with photos of aborted fetuses. Around campus and the town of South Bend, trucks displayed similar images, offering a literal symbol of the issue at the heart of the divide: abortion.

For bishops and others opposing the invitation, they argued that Obama receiving an honorary doctorate violated the U.S. bishops' 2004 document on "Catholics in Political Life," which suggests withholding honors from politicians whose views conflict with church teaching. For those in support, they made the case that a document on Catholics in political life did not apply to Obama, as he is not Catholic. Further, many viewed the occasion of awarding the nation's first Black president as coming full circle with the pioneering civil rights work of longtime Notre Dame president, Holy Cross Fr. Theodore Hesburgh.

Kathleen Sprows Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, who was teaching a class at that time on "Catholics in America," told NCR the campus debates were professionally and pedagogically very rewarding, as they led to lively conversation with her students. Yet personally, she said they were "very painful" and that the campus environment was a "zoo" during the weeks leading up to commencement.

While she said it has become billed as a tradition that the university invites presidents during their first year in office, she says that characterization is a bit "overstated," noting that while the number of presidents speaking on campus is impressive, the timing and occasions of those invites have varied.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, left, receives an honorary degree from University of Notre Dame President Holy Cross Fr. John F. O'Hara at a special convocation in December 1935. Roosevelt was the first U.S. president to receive an honorary degree from the university. (Courtesy of University of Notre Dame Archives)

A 'national university' invites the nation's president

Long before there was a nationally prominent football team, Notre Dame had a mission to be a national Catholic university where "what happens at Notre Dame matters," said Sprows Cummings, who is currently teaching a course on Notre Dame and America.

"Whereas other universities grew up regionally, Notre Dame was national from the very beginning," she said. "In the 1930s, there was a conscious effort for the university to make a name for itself on the national stage."

President Franklin Roosevelt became the first sitting president to visit Notre Dame, where Holy Cross Fr. John O'Hara, the university's president, conferred him with an honorary degree at a special convocation in December 1935. The occasion was a ceremony marking legislation that would lead to the independence of the Catholic majority nation, the Philippines.

A year later, in 1936, O'Hara hosted Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli who was then the Vatican's Secretary of State and three years later would be elected Pope Pius XII, making O'Hara the first university president to confer honorary degrees on a pope and a president.

Roosevelt was followed by Dwight Eisenhower, who in 1960 became the first sitting president to receive an honorary degree and deliver the commencement address. In 1950, John F. Kennedy served as a commencement speaker, but he did so as a member of Congress prior to his election as president.

President Gerald Ford received an honorary degree while speaking at a St. Patrick's Day convocation in 1975, followed by commencement addresses and honorary degrees awarded to President Jimmy Carter in 1977 and Ronald Reagan in 1981. President George H.W. Bush delivered remarks and received his honorary degree at the university's sesquicentennial year exercises in 1992, and President George W. Bush spoke at commencement and received an honorary degree in 2001, followed by Obama in 2009.

In 2017, Vice President Mike Pence, a past governor of the state, spoke at commencement and received an honorary degree, widely viewed as a way to sideline anticipated protests surrounding a potential invite of President Donald Trump. Even so, when Pence began to speak, an estimated 100 students quietly walked out in protest.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, center, rides with Cardinal Giovanni Montini, right, a fellow honoree during the University of Notre Dame's 1960 commencement. Montini became Pope Paul VI in 1963. (Courtesy of University of Notre Dame Archives)

Biden at Notre Dame: 2009 redux?

Writing in Notre Dame's The Observer newspaper last month, senior Vince Mallett argued that the university should invite every sitting president as a matter of policy.

"This is not because the University should be politically neutral," he wrote, "but precisely because the University has an obligation to be political, and that obligation demands that we do not cut ourselves off from the world simply because of its sin."

Yet although he wants Jenkins to extend the invite to Biden and for the president to accept, he acknowledged that such an invite to Biden this spring will result in "countless protests, counter-protests and speeches, annoying media coverage, disappointed alumni and vitriolic comments."

By contrast, Sycamore Trust's open letter to Jenkins, which views a Biden invite as an assault on the university's Catholic identity, has gained over 2,500 signatures. The letter argues that "the case against honoring him is immeasurably stronger than it was against honoring President Obama," and that "Biden's actions already taken and those promised will result in the killing of countless innocent unborn both here and abroad through federal funding of abortions and abortion organizations."

Sycamore Trust is an independent organization formed in 2006 by alumni who, according to its website, were concerned about the "weakening of the Catholic identity" at the school.

George H.W. Bush speaks at the University of Notre Dame commencement May 17, 1992. (Courtesy of University of Notre Dame)

Set against the backdrop of some bishops arguing that Biden should be denied Communion, while Pope Francis and the Vatican signal their desire for a positive working relationship with the new administration, the historic nature of a sitting Catholic president headlining the commencement ceremony of the nation's premier Catholic university will inevitably be a combustible mix.

Along with the speaker announcements, other details surrounding this year's commencement remain murky due to the global pandemic, which could be one reason the university could opt to forgo a presidential invite, be it for practical or political reasons.

Last May, Jenkins took to the pages of The New York Times to argue that campus would reopen in fall 2020 despite complications related to the pandemic, becoming one of the first major universities to make such a call, and Notre Dame has remained in the national spotlight over the last year.

In October, Judge Amy Coney Barrett, a Notre Dame alumna and faculty member, was confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Nearly 20 Notre Dame faculty members attended a White House ceremony Sept. 26 announcing her nomination, which was criticized as a COVID-19 "superspreader" event. Jenkins was spotted there not wearing a mask, a decision he later apologized for after contracting COVID-19 himself. At the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, among the Trump flags and "Stop the Steal" banners, a "God, Country, Notre Dame" flag could also be seen on display.

Given the recent spate of unwelcome scrutiny, Notre Dame may decide to punt on or postpone another national controversy. Yet should Biden receive and accept an invite to campus, whenever that may be, it's likely that some of the very individuals and groups present in the White House Rose Garden last fall will be the very ones protesting his arrival, reflecting both a divided church and campus.