March for Life participants demonstrate near Union Station in Washington, D.C., Jan. 29, 2021. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

For almost a half century, the hundreds of thousands of anti-abortion activists who gather every year for the March for Life in Washington, D.C., have dreamed of a post-Roe America.

On Jan. 21, the 49th annual March for Life will kick off as the U.S. Supreme Court appears poised to carry out that longstanding goal of overturning Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion across the country. At the precipice of a long-awaited milestone, the March for Life has reached a crossroads. It may not be the same moving forward.

"We've always been looking to have Roe overturned, and this year we're actually looking at that being a real immediate possibility. So that definitely takes the symbolism of the march to another level," said Terrisa Bukovinac, the founder and executive director at Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising, a Washington-based nonprofit.

Like hundreds of thousands of other people, Bukovinac will be marching in the nation's capital on Jan. 21, a day before the anniversary of the court's landmark 1973 ruling in Roe.

"Roe in many ways gave birth to the March for Life, and the pro-life movement is birthed from the March for Life," Bukovinac told NCR.

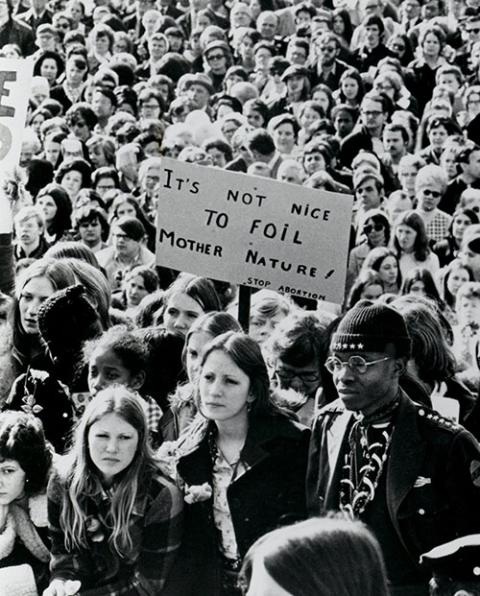

Young people take part in the first March for Life in 1974 in Washington. (CNS)

Since 1974, when the first March for Life was held to mark Roe's one-year anniversary, the controversial ruling has been an organizing principle and animating force for the march. Over the years, it has attracted politicians, mostly Republicans, to address the throngs of anti-abortion activists who rally at the National Mall before marching from the Washington Monument down Constitution Avenue to the Supreme Court.

"This is what the pro-life movement has rallied around for nearly 50 years," Bukovinac said.

Nearly a half-century later, Roe's days appear numbered. Many legal experts expect that the high court later this year, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health, will uphold a Mississippi law that bans most abortions after 15 weeks. Such a ruling would essentially set aside the court's abortion precedents in Roe and in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which widely affirmed Roe in 1992.

"There is an outside possibility that in June when the law comes down, the justices could fashion a compromise. But for a number of reasons, it's likely that Roe and Casey will be overturned in June," Erika Bachiochi of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a conservative think tank, told a virtual Georgetown University panel on Jan. 19.

Jennifer Holland, a University of Oklahoma professor who has written about the history of the anti-abortion movement, told NCR that the movement is on "the cusp of an immense success."

"Even before this, I would consider the movement to be incredibly successful, just by their ability to curtail abortion access, especially on the state level, and with the political power that they've been able to cultivate over time," Holland said.

A significantly weakened or overturned Roe would fulfill the longed hoped-for dreams of March for Life participants, though it could also bring some changes for the annual event and its two affiliated nonprofits, the March for Life Education and Defense Fund and March for Life Action.

"What will happen, I suspect, should Dobbs restore the right of a state to outlaw abortion, is that you'll see state-level marches for life grow with great enthusiasm because the battle will happen principally at state capitals," said Victoria Cobb, president of the Family Foundation of Virginia, a socially conservative nonprofit.

Advertisement

Cobb, who helps to organize the Virginia March for Life, told NCR that she hopes to attend the national March for Life in Washington D.C., which she expects will have a heightened sense of "urgency and excitement" this year.

"Pro-lifers know what's at stake in that [Dobbs] decision, and therefore the energy required nationwide to protect human life," Cobb said. "There's great optimism that the decision will restore abortion public policy issue to the states."

A spokeswoman told NCR that Jeanne Mancini, president of March for Life, was not available for an interview. But pro-life activists who have participated in the march and its affiliated discussion panels, theme launches and rallies shared their thoughts for how a post-Roe landscape might shape the march in the years ahead.

"They're going to have to change their focus, in the sense that it'll have to be more local," said Gloria Purvis, an American Media podcast host who has long been involved in Catholic pro-life circles, including as a member of the Maryland Catholic Conference's Respect for Life Advisory Board.

"It could be that the march would still happen nationally if Roe were overturned, in the sense that it would be a place for Americans to march and remember, maybe like a memorial march for the lives lost, a 'never forget' type of thing," Purvis told NCR.

Gloria Purvis participates in a virtual dialogue Jan. 18 on the "Pro-life Movement at a Crossroads: Dobbs and a Divided Society." (CNS screencap/YouTube/Georgetown University)

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa, president and founder of New Wave Feminists, a Texas-based secular "whole-life" nonprofit, told NCR that her "biggest fear" is that a post-Roe complacency will set in among anti-abortion activists.

"It's really important that people realize if Roe is overturned, that is when our work begins, not when it ends," she said.

Cobb, who will be participating in a "post-Roe" discussion panel the day before the March for Life, told NCR that the annual event — which attracts participants from across the country — has been a "momentum generator" and unifier for the anti-abortion movement.

"It creates and builds towards moving the public opinion on abortion," she said. "It puts pressure on our congressmen and women to speak on the issue of life, to make an impact where they sit."

The March for Life's political impact is undeniable. In the last two decades — in which the once all-volunteer organization grew to a professional operation with $1.8 million in contributions in 2019 — the March for Life has mobilized hundreds of thousands of people to petition federal lawmakers to strip Title X funding from Planned Parenthood and to advance various anti-abortion bills.

The March for Life has taken credit for activating followers to pressure Republican politicians to appoint conservative justices to the Supreme Court, beginning with Samuel Alito in 2006 and more recently with former President Donald Trump's appointments to the high court: Neil Gorsuch in 2017, Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 and Amy Coney Barrett in 2020.

In 2017, Vice President Mike Pence addressed the March for Life, as did Trump in 2020, the first sitting president to do so.

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa joins in a virtual dialogue Jan. 18 on the "Pro-life Movement at a Crossroads: Dobbs and a Divided Society." (CNS screencap/YouTube/Georgetown University)

"Having the president of the United States [address the March for Life] signifies that this issue has reached the topmost hallowed hallways of America and is now being addressed," Cobb said.

But the march's cozy ties with conservative politics, Trump especially, come at a cost. Herndon-De La Rosa described the March for Life in recent years as having the feel of a "MAGA rally," a reference to Trump's "Make America Great Again" campaign slogan.

"I would say that gave the movement a black eye. It was bad optics-wise in a lot of ways," said Herndon-De La Rosa, who added that "half of the signs" she saw at the pre-march rally in recent years declared Trump "the most pro-life president ever."

"In my mind, that has no place in a March for Life because it is very divisive and exclusionary to people who don't believe that way but who still support the rights of the unborn child," Herndon-De La Rosa said.

Even before the Trump era, the close connections to right wing politics made the pro-life movement "a tough sell" to many, especially in the Black community, Purvis said.

"The movement had already been widely perceived as something for Republican white men, and that called for anti-woman, anti-Black, anti-poor" attitudes," Purvis said. "When it's perceived as all that, it's a turnoff."

Terrisa Bukovinac addresses the national conference of the Democrats for Life of America in East Lansing, Michigan, in 2019. (Don Clemmer)

At the Jan. 19 virtual panel, hosted by Georgetown University's Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, University of West Georgia history professor Daniel Williams spoke of a need to "depoliticize" the pro-life issue.

"The pro-life movement is identified with a Republican Party that a number of people who are not part of it, who are skeptical of Trump, view as dangerous to American democracy," said Williams, author of Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-life Movement before Roe v. Wade.

Cobb, of the Family Foundation of Virginia, said March for Life organizers are not so much to blame for the politically conservative "feel" of the event, as there are relatively fewer pro-life Democrats in public life willing to speak out on the issue.

"If you are a Democrat and you stand for life, you will have groups like Planned Parenthood come after you in the nomination contests," she said.

Bukovinac — who is also the vice president of Secular Pro-Life and describes herself as atheist, leftist and vegan — said it can be "extremely difficult" for someone with her political views to work in a movement seen by many as monolithically Christian and Republican.

"But it's so critical," she said. "Every social justice movement has to deal with these kinds of things. There is no victory without unity. The cause of protecting the unborn is just so paramount in my worldview. If I'm not willing to work through the difficulties of working with people who are so different from me, then we're not going to see a victory. And that victory is absolutely critical, so I just do it."

The March for Life, Bukovinac added, has reached a "milestone" in 2022, but she doubts there will be significant changes looking ahead.

"There are always going to be people who will gather around this issue for as long as abortion is legal in America," she said.