Trappist monks and a guest are pictured at the Monastery of Notre Dame de l'Atlas near Medea, Algeria, in this undated photo. Seven Trappist monks of the monastery were kidnapped in 1996 by the members of the Armed Islamic Group and killed. (CNS/Courtesy of the Vatican Dicastery for Communication)

There are no ghosts at the Notre Dame de L'Atlas Monastery in Midelt, Morocco, but there are memories. It is in this city in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains where the two Trappist monks who survived the massacre of their community in Tibhirine, Algeria, re-established their community.

Reminders of the past are close at hand. A painting in the abbey chapel depicts the slain monks from Tibhirine in prayer; the guest rooms at the abbey bear their names; a memorial to them shows their portraits. Brothers who gave their lives for peace and friendship are gone but not forgotten here.

Along with 12 other Christians killed during the Algerian civil war in the 1990s, the seven monks from Tibhirine was beatified in December of 2018. They are considered martyrs, their deaths part of the toll exacted during a war marked by the brutal massacres of civilians.

Detail of a painting hanging in the monastery chapel in Midelt, Morocco, showing the seven slain monks of Tibhirine at prayer. (W. M. Hughes)

Early in the morning of March 27, 1996, members of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA, for Groupe Islamique Armé) arrived at the abbey in Tibhirine and kidnapped the seven monks they found there. Missives between the GIA and the Algerian and French governments were exchanged as the GIA sought to trade the monks for a GIA leader arrested three years earlier. The monks were held for two months. Their decapitated heads were found at the end of May in 1996, and buried in the cemetery at Tibhirine on June 4. The events leading up to the abduction of the monks at the Notre Dame de L'Atlas monastery in Tibhirine are the subject of the 2010 award-winning movie, "Of Gods and Men."

Fr. Jean-Pierre Schumacher and Fr. Amédée Noto owe their lives to being in a different part of the monastery when the guerrillas arrived. "There was no noise. There was nothing remarkable," Schumacher said of that night which was to mark his and the other monks' lives forever.

With the death of Father Amédée in 2008, Father Jean-Pierre is the only surviving member of the monastery at Tibhirine. Pope Francis paid tribute to him during his visit to Morocco at the end of March, kissing his hand in a gesture of respect and reverence.

Pope Francis kisses the hand of Trappist Father Jean-Pierre Schumacher, 95, the last survivor of the 1996 massacre in Tibhirine, Algeria, during a meeting with Catholic priests and religious and leaders of other Christian churches at St. Peter's Cathedral in Rabat, Morocco, March 31. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Now 95, Schumacher remains a witness to events that are even today still shrouded in mystery. The deaths of the monks were blamed on Islamic jihadists, but suspicions linger that the Algerian government and possibly the French government too may have been involved. A Time magazine story in 2009 reported that testimony of a retired French general indicates the deaths may have been the result of an Algerian military operation gone awry. The bodies of the monks were never found.

"One doesn't know," said Schumacher. "It's a mystery that has not been cleared up."

Small and frail, the monk speaks in a clear voice about the dark days of the Algerian civil war.

"One lived in a climate of total insecurity from day to day," he recalled. The monks at Tibhirine had been warned to leave Algeria. They held serious discussions about going but decided to remain despite the danger they felt closing in on them. They had come to Algeria not to convert Muslims but to live in friendship with them. Since 1938, when the monastery was founded, they and their Muslim neighbors had lived in harmony. The monks called the Algerian army "our brothers of the plain" and the rebels "our brothers of the mountains" in hopes that one day the two would become truly brothers. Pressed to take sides between the Islamist guerrillas and the Algerian government, they refused.

Advertisement

Schumacher was the night porter at the abbey. As such, everyone expected he would be the first to be affected by the danger to the community. But the guerrillas who arrived after midnight entered not by the main door but the basement. Schumacher never heard a thing. It was not until hours later that he and Noto discovered what had happened.

While the filmmakers visited Notre Dame de L'Atlas in Midelt, "Of Gods and Men" was filmed at an abandoned Benedictine monastery about 25 kilometers away.

Partly because of the popularity of the film, the monks' courage and fidelity to their calling have become well-known. But the monks at Tibhirine were not unique in that, said Schumacher.

"All the Christian communities opted to stay in Algeria with the suffering people to help them," he said. "The entire church had this attitude."

And it was not only Christians who resisted the tide of violence washing over Algeria in the wake of the government losing an election in 1991 and then refusing to cede power. Schumacher noted that 114 imams lost their lives because they opposed the violence sweeping the country.

After the deaths of the monks in his community, Schumacher was haunted by the question of why he had not been taken too.

"Was my heart not ready?" he asked himself. "Was the lamp not lit?"

A letter from an abbess of a Cistercian monastery in Switzerland provided consolation. She asked about his interior life and told him not to be troubled by anxiety or apprehensions — that God had taken seven men to witness to him by their deaths and left others to witness by their lives.

Schumacher has no doubt of that.

Father Benoît (W. M. Hughes)

"It's God who drove that history," he said of the events of 1996. "What happened to that monastery became an image for the entire world. An image of reconciliation. It's a call to all today."

The community at Midelt is small, only a half-dozen monks drawn from different countries. Still, it is an active place. Father Benoît, the monk who greeted me at the entrance of the monastery, said people from outside Morocco frequently travel to the monastery to visit Fr. Jean-Pierre Schumacher. A group of French students doing an internship in Morocco were staying at the monastery when I visited. A meeting of the Little Sisters of Jesus was taking place, the score of religious women gathered there drawn from a half a dozen places in Algeria and Morocco. The sisters, like the monks, are inspired by the example of Charles de Foucauld, a French cavalry officer, explorer and geographer turned priest who lived in the Sahara among the Tuareg people of Algeria before his death in 1916.

A small chapel at the monastery is dedicated to him. Next to it, another is devoted to Fr. Albert Peyriguère, a Frenchman so moved by the example of his countryman that he set out to emulate him in Morocco, settling down in the small town of El Kbab and providing medical aid, food and clothing to the indigenous Berber population around him. Like Charles de Foucauld, he collected stories, songs and poems of the local people, becoming an ethnologist and Berber specialist.

"He became more Berber than the Berbers," said Father Benoît, who described Peyriguère, whose tomb lies in the chapel, as an extraordinary individual, a spiritual father to the monks and a man much loved by the local people whom he helped. Born in 1883, he died in 1959.

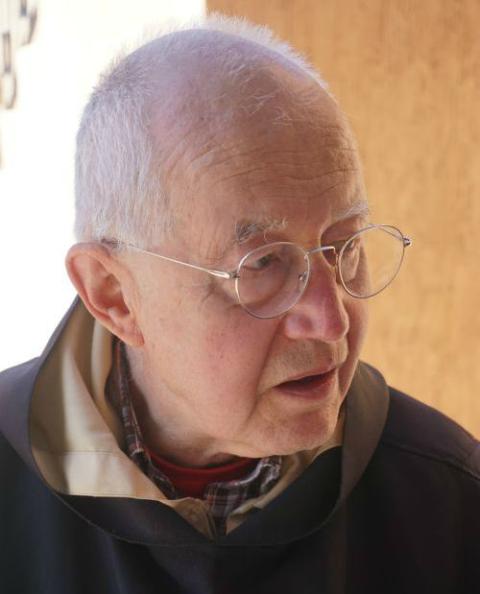

Fr. Jean-Pierre Schumacher (W. M. Hughes)

Talk turned to politics, to the massive peaceful demonstrations in Algeria against the government and to the Trump administration.

"The Shiites are the Muslims closest to us as Christians," Father Benoît said. "Why does Trump pursue this policy with Iran?"

When almost 20 years ago Notre Dame de L'Atlas relocated to Midelt from near Medea, Algeria, the monks took over quarters formerly occupied by religious women belonging to the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary. "They were very loved," Father Benoît said. A policeman posted at the entrance to the monastery left me wondering if the monks felt threatened, but the priest said relations between the monastery and the community are excellent. He thought police had been posted at the gate after terrorist attacks in France.

"The people are happy that we're here to show that Christians and Muslims can live together," he said.

He introduced me to a sister walking across the courtyard of the monastery, a member of the Little Sisters of Jesus, a religious order founded in Algeria in 1939. Following in the path of Fr. Charles de Foucauld, the Little Sisters of Jesus are contemplatives sharing everyday life with workers, minorities and other people who are materially poor or are ignored, disregarded.

Originally, the Little Sisters of Jesus lived among Muslims, its foundress settling among nomads in the Sahara desert. Since its establishment, the order has grown. Members of the Little Sisters of Jesus are now present in 63 countries where they try to be a bridge between all races, classes and religions. Sr. Anne Yvette said she and the other sisters seek "a life of friendship and prayer and presence, a witness to a larger fraternity."

Today, more than ever, fraternity seems elusive in the world, but the mission of the monks in Midelt seems no less critical because of that. In our conversation, Fr. Jean-Pierre Schumacher spoke of the need for dialogue, the need for a new equilibrium in the world. It's his hope that the deaths 23 years ago of his brother monks in Tibhirine seed a new spirit of reconciliation.

In a polarized world, mention of "dialogue" can seem almost quaint, but it's not lost any of its purchase for a man who survived a civil war and the assassinations of his brothers. As I left him, he asked if the publication I write for is one that engenders dialogue.

[Margot Patterson is a writer and editor based in Kansas City, Missouri.]