Jesuit Fr. Raymond A. Schroth, top left, poses with staff of The Maroon, the student newspaper of Loyola University New Orleans, for a yearbook photo in 1994. (The Wolf yearbook archives)

Jesuit Fr. Raymond Schroth, a journalist, longtime contributor to NCR, and a professor for decades at a number of U.S. Jesuit schools, died July 1 at age 86. NCR reached out to some of his former students for their recollections. Following are their reflections on his teaching, his friendship and the impact he had on the course of their careers in journalism.

Jim Dwyer (Wikimedia Commons)

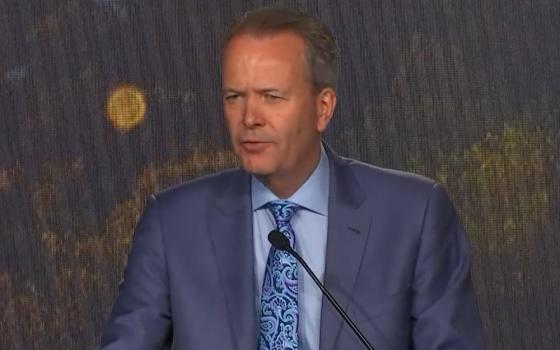

Jim Dwyer

Journalist for The New York Times since May 2001 after stints at the Daily News, New York Newsday and several papers in northern New Jersey. He has written the About New York column since 2007. The winner of the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for commentary and a co-recipient of the 1992 Pulitzer for breaking news. Fordham University graduate.

Ray lived in the dorms, left his door ajar while he was awake, and students were welcome to arrive unannounced, and did. In September 1975, I moved into his dorm at Fordham.

Every wall in his little sitting room was lined with books. Posters from campus demonstrations, pictures of friends and of strangers he admired, were displayed on the wall. For an 18- or 20-year-old college student, his little sitting room was a portal to the wider world, not only of the grand public affairs of the day, but also of adulthood. There, you were taken seriously.

Ray's regular courses were always in high demand, even though he was widely known as one of the most demanding teachers at the university, requiring a book every week, detailed notes and a fresh writing assignment. If you missed a deadline, the paper was graded F.

He also held seminars in his sitting room once a week, eight or 10 students seated on the couches or armchairs, and though these were for students in the dorm, there was no neighborly slack cut. At midnight, he crossed the road to say Mass in the chapel.

One thing was certain: As hard as Ray worked his students, he drove himself even harder. Anyone who pushed open his door would find him in the middle of grading papers or preparing for a class or working on an essay for publication in Commonweal or America or NCR. His to-do list could have been written on a treadmill.

One August, I snuck back to campus a few days ahead of the official opening, and moved into my dorm. As I was carrying in my things, I saw that Ray's light was on.

Tapped on his door, and pushed it open. He hollered a welcome, not knowing who was arriving. I found him seated at a chair with a cardboard box at his feet. On the desk was a stack of handwritten pages. Page by page, he ripped them into pieces and dropped them in the box.

"What are you doing?" I asked.

"Tearing up my old notes for the books I am teaching this fall," he said.

"Why?"

"To make myself read them again," he said.

That was Ray.

Rose French (Provided photo)

Rose French

Digital producer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, where she has worked since 2013. She has nearly 20 years of experience as a journalist, previously working at the Star Tribune in Minneapolis, the Associated Press, The Tennessean, Newsday, The Times-Picayune and the Alexandria Town Talk. She graduated from Loyola University New Orleans with a bachelor's degree in journalism.

I did not have the opportunity to take one of his classes at Loyola University New Orleans (where I attended 1994-98), but I was a staff writer for The Maroon my freshman year (1994-95) while he was the student newspaper's adviser. And he was profoundly influential for me, to say the least. His editing, his critiques, his warmth, his wit and humor, his love and encouragement.

I attended Catholic school kindergarten through 12th grade, but never had I ever met a priest quite like Fr. Schroth. He honestly seemed to care about us young fledgling reporters and editors at The Maroon. He took us seriously as student reporters. He listened to us. He held very high standards he expected us to achieve (or come very close to achieving). You wanted to do your absolute best always — not only for yourself and fellow student reporters and editors but for him, too. He made us all better reporters and editors, critical thinkers.

I am so grateful for Fr. Schroth for many things. Namely, teaching us all how to fight the good fight, to never give up even when the odds are not in your favor. Even when it all feels overwhelming and you want to despair. He and other Jesuits taught me at Loyola about the importance of social justice, that there must be action alongside one's faith, the sitting in the pews. Without action to try and right the wrongs, all the world's injustices, we are lost. He's a big reason why I've continued to do journalism nearly 22 years now. I've carried his lessons throughout my life and hope to pass them on to my two children.

The last significant time I spent with Fr. Schroth was in 2004, when I was in graduate school at New York University, where he was teaching an undergrad journalism class. We met at a Starbucks at Astor Place and talked about the class he was teaching, what articles he was working on. He was always working. Right up until the end. Which was just one of the many things about him that was so incredibly impressive and inspiring. Always writing, seeking, observing, teaching, questioning, probing, empathizing, shining light where it was needed. As a J-school student, you couldn't ask for a better role model and mentor. He was also a good friend, encouraging you, rooting for you, even as he was merciless sometimes with the edits.

Michael Wilson (The New York Times/Earl Wilson)

Michael Wilson

Michael Wilson has been a reporter at The New York Times since 2002, writing stories for the New York, National, International and Arts sections, as well as the Crime Scene column. He studied journalism at Loyola University New Orleans.

I met Ray as a nervous sophomore, asking if I could still join his journalism class after the deadline had passed. The class was full, he said, "but one more won't make a difference." I smile when I think of that day, because it made a lifetime of difference for me.

Ray was incredibly, infuriatingly demanding as a teacher, assigning quantities of homework that assumed his was the only class you were taking. But he was, looking back, so very generous and, if it's the right word, careful. He was careful in conveying the promise he saw without showing you how much garbage that promise was hidden under. He protected you from your own bad writing, from discouraging yourself out of believing you could take a shot at this as a career.

Ray addressed you, a 19-year-old kid, as a peer. He arranged his students around a long table, and took his own seat among them, not behind a desk. It became clear that he was doing the same homework that you were — if he was teaching a book he'd read once or a dozen times, he'd read it again, to stay fresh. We were all in this together. And when he praised your writing, with a scribbled note in the margin of the piece, there was no higher praise.

He taught by example, a working journalist who shared his own writing alongside the masters. Those stories taught us that journalists travel to the most miserable and uncomfortable places to tell what was happening there. That those without power were the first to be quoted, the point of the story.

I can recall no more productive professor, no one busier between his classes and travel and writing. And yet he never turned down an invitation to a party or a round of beers in the campus pub. He loved the gamut of university life, of being a part of student life.

Jesiut Fr. Ray Schroth, right, presides over the nuptial mass for Loretta Tofani and John White at the Annunciation Church in Crestwood, New York, in 1983. (Courtesy of Loretta Tofani)

Loretta Tofani

Loretta Tofani reported for The Washington Post and for The Philadelphia Inquirer, where she served as the paper's Beijing Bureau chief from 1992 through 1996. Now retired, she has received much recognition for her work, including a Pulitzer Prize in 1983 for her investigation of rape and sexual assault in the Prince George's County, Maryland, Detention Center. She received a bachelor's degree from Fordham University.

Ray Schroth was my journalism professor in college and also my friend throughout my life. He said the Mass for my wedding in 1984 and baptized my twin son and daughter in Philadelphia in 1998. Ray was a role model. He taught me that journalism could be a force for change, and that an important role for journalists was to give voice to the underprivileged. He inspired me to use the values I had absorbed as a Catholic throughout my 25 years as a journalist.

As a reporter, I found many opportunities to report and write the types of stories that Ray admired — stories that other journalists did not seem to even see. In 1983, while a reporter for The Washington Post, I wrote a series of articles on men getting gang-raped in a county jail. The men were not convicted of any crime; they were charged with misdemeanors like shoplifting and malicious destruction of property. They were in jail because they did not have any money for bail. It was the type of story that Ray taught me to spot. It won a Pulitzer Prize in 1983. More importantly, the series caused jail officials to change the conditions that had led to the gang rapes.

Years later, in 2008, working as a freelance writer, I reported and wrote a series on Chinese workers getting limb amputations and fatal diseases while making products for America. I traveled to China numerous times to interview the workers and get their medical records. The series was published in The Salt Lake Tribune and won several national awards. It also caused some corporations to be more careful about which factories they used to have products made for America.

As a journalist, I was sensitive to certain types of stories, and I owe that sensitivity to Ray Schroth. I last saw Ray in 2016, when we had lunch at a restaurant in Little Italy. He let me know, gently, that I had disappointed him. I had retired. But he was planning to write another book. I will miss Ray terribly.

Advertisement

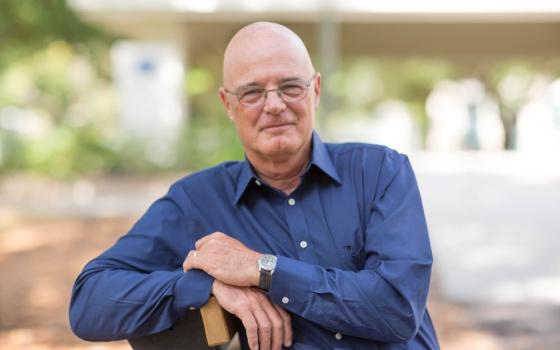

Neal Falgoust

Neal Falgoust was a newspaper journalist for seven years in Buffalo, New York, and in Galveston and Corpus Christi, Texas, covering school districts and local governments. Left the profession in 2006 to attend law school and was licensed as an attorney in Texas in 2009. Graduate of Loyola University New Orleans in 1999 with a bachelor's in communications.

I met Schroth during my freshman orientation. He was my academic advisory (I don't remember if he was assigned to me or if he chose me), and he insisted that I take his "Intro to Mass Communications" class. I did not know at the time that he was regarded as one of the most demanding professors on campus. I had gone to Jesuit High School in New Orleans, so I had some idea of the academic rigor to expect from a Jesuit professor.

He also marched me down to The Maroon offices and told me I had to start writing. He said the only way to get better was to do it again and again.

Going in to my second semester, I was asked to join the editorial board of The Maroon, and I knew I would be taking Schroth's spring "Intro Writing" class. Schroth also talked me into taking an advanced "Travel Writing" class. So, here I was in my second semester as an undergrad, helping lead the student paper and taking two Schroth classes. I didn't know what I was getting into.

About six weeks into the semester I had to drop the Travel Writing class because I could not keep up with the assignments. (For just his Travel Writing class, one week's worth of assignments might consist of reading Walden and writing a three-page essay of a personal journey into wilderness using the same observational techniques as Henry David Thoreau.) I was so afraid that I would be a disappointment to him, but he was understanding and gracious.

At that time, I did not know he would be leaving Loyola at the end of the spring semester to return to Fordham. When he announced his departure, he asked if I would join him on the road trip from New Orleans back to the Bronx, New York. He, of course, insisted we take the scenic route through the Smoky Mountains (with a stop in Gettysburg). We listened to Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald musicals and recordings of Edward R. Murrow's broadcasts from the London rooftops during World War II, and he talked a lot about his biography of Eric Sevareid.

I think he was so beloved by his students because, for many of us, he was the first person to treat us as adults. We showed up in his class at 18 years old out of high school, and here was this 60-something stone-faced Jesuit priest who interrogated us as his equal and demanded excellence from us. He asked us what we were reading, what we were writing, provided us critiques and challenged our views, many of which we had simply adopted from our parents.

When I left Loyola, he gifted me two periodical subscriptions: National Catholic Reporter and Commonweal. My parents were so confused when they started arriving in the mailbox.

As for his legacy, there are two generations of journalists, attorneys and public servants whom he taught and who have not yet completed their careers. I think we will be his legacy, and it is up to us to write it.

My entire career has involved holding those in power (especially in government) accountable and serving marginalized communities. Both of these reflect what I believe to be Schroth's core values: holding power to account, courage and empathy.

Eileen Markey (Jennifer MacKenzie)

Eileen Markey

Eileen Markey is author of A Radical Faith: The Assassination of Sister Maura (Bold Type Books/Hachette) and is an assistant professor of journalism at Lehman College of the City University of New York. A Fordham University graduate.

I was a student at Fordham when I met Ray Schroth. It was his third rotation at the place that more than any other was his home. He'd been at Fordham as an undergraduate in the 1950s, then returned as a young Jesuit in the 1970s. Now in the mid-1990s, I picked up the phone in my dorm room in Martyrs' Court and heard: "This is Raymond Schroth. I read your editorial in The Paper [Fordham's alternative student newspaper, modeled on the Village Voice]. It was very good. I'd like to take you to dinner."

I think it was his first year back at Fordham, this time as an assistant dean, and he was looking for new friends. Relations between faculty and students had grown more formal and distant in the two decades since Ray had lived in A house at Martyrs and celebrated nightly Mass at midnight in his room with students. But he was intent on establishing relationships with students.

Ray took friendship seriously, cultivated and nurtured friendships as part of his vocation. He saw this as an extension of Christ's ministry, as he reminded us in Holy Thursday emails he sent every year. This one from 2017 is typical: "As you know, Holy Thursday is that feast in which I pray in gratitude for the friends God has given me. As I write this, our nation and the world are suffering terribly from inequality, homelessness, bigotry and war. But Jesus lived and died trying to convince us to 'love one another' as he has loved us. I know that you will join me in prayer both for those we love and for those who cry out for both love and justice. Love, Ray."

The year before, he wrote: "Holy Thursday is the day on which Jesus, at the Last Supper, taught us more about the Father's love, expressed his love for all of us and told us to love one another. At Mass tomorrow I will thank the Father above all for the love He has given me through you. Throughout my life it has become more and more clear to me that without your friendship I would be nothing."

Ray was able to draw all these friends to himself because he took students seriously, paying attention to what we thought, cheering our growth and maturation, demanding rigor because he believed we had better work in us. Those high expectations made us reach.

But the almost comical rigidity (exemplified in his ramrod straight posture, even before a back injury meant he literally did have a rod in his back) and formality were leavened by great sweetness. He took such joy in our joys and pride in our accomplishments. He was interested in what we were doing, what we were reading, what we were experiencing in our careers.

He maintained a trail of friendships from each of the many colleges where he was stationed, even as he came into conflict with most of his Jesuit superiors and the deans and presidents he served under. That reputation made us like him. It's not that he wasn't afraid to ruffle feathers. He took pride in it. It was a personality trait, or flaw, that appealed to the many of us friends of Ray who are journalists.

When my husband, fellow Fordhamite and fellow journalist Jarrett Murphy, and I got married, it was obvious that we would ask Ray to witness the sacrament. When our children were born, of course we asked Ray to baptize them, in the University Church. It was difficult to see him grow infirm because it so clearly rankled him, injured his tremendous pride to be confined, tore at him not to be able to dine and drink with his many friends. It is good to think of him now, at a great table. Martini in hand.

Hank Stuever (The Washington Post)

Hank Stuever

Hank Stuever, The Washington Post's TV critic since 2009, joined the paper in 1999 as a reporter for the Style section, where he covered popular (and unpopular) culture across the nation. Stuever previously worked at newspapers in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Austin, Texas. Loyola University New Orleans, bachelor's degree in journalism.

We're all pretty good at remembering Ray's intellectual rigor and how demanding and challenging he was in the classroom — to do well in his class indeed felt like a real accomplishment. It was only years later that I realized the depth of his love for us, his way of treating us as fellow travelers on the same journey of seeking truth and telling stories clearly and courageously.

He was 52 when he came to New Orleans in 1986 to teach at Loyola, and I was an 18-year-old freshman. I now see what sort of generosity it takes to believe that an 18-, 19-, 20-year-old student could become the next Graham Greene or Neil Sheehan or Joan Didion. He had that sort of faith in us, that level of expectation. He loved those who were up for the challenge and he also loved us when we fell short.

One night in my first semester of freshman year, Ray knocked on my dorm room door and asked if I wanted to go see a movie by a new director he'd read about in The New York Times — a young black filmmaker named Spike Lee. I said yes and we walked to the theater.

On the way back, Ray wanted to know what I thought of the movie — and not just whether or not I liked it. Was it as good as the writer from the Times seemed to think it was? What message did it have for us? What's something the audience could get from having seen it? I think he was testing me, a bit. Was I the kind of learner he hoped I was? Did I have a critical eye? Did I have the ability to say what I mean?

There you have the foundations of good cultural criticism — something Ray did for many years at NCR and elsewhere, one part of his extraordinary talent as a reporter, author and thinker. I treasured my time with Ray as a teacher and then as a friend and mentor through three decades of my career. Whenever we would get together, once or twice a year, Ray and I would talk about everything under the sun, but the thing we most loved talking about was the work: What are you working on? What are you reading? What are you writing? What do you think? This was true right up to the last time I saw him, last fall.

There are many of us who cannot imagine what direction our lives and careers might have taken without him. He wasn't all-powerful, he wasn't one of those media figures who can just pick up a phone and open a door to a job opportunity. Better than that, it's his sense of moral courage and discipline that sticks with you. It's very much a voice in my head, still and always, when I write.