A woman outside the Glynn County Courthouse in Brunswick, Georgia, raises her fist Nov. 24, after the jury reached a guilty verdict in the trial of William "Roddie" Bryan, Travis McMichael and Gregory McMichael, convicted of the February 2020 murder of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery. (CNS/Reuters/Marco Bello)

If ever there were a time in American history in which a beatitude calling us to "hunger and thirst for righteousness" would seem unduly important, this must certainly be it.

Not because the country is in any kind of unusual or intense military conflict. Not because climate change is threatening our immediate survival as a nation. Not because global economic collapse is upon us. Not because we're facing a new surge of COVID-19 and a new international variant, omicron, in the unmasked faces of a looming winter. Not even because our voting rights are now endangered or the results of our last presidential election have been admitted to be true, publicly or not. (After all, we all know the truth of it — Republicans and Democrats alike.)

All of those things are real, of course.

But worse than the impending doom that comes with the regular cycles of stress and strain with which countries must deal, lie three other problems that Jesus, looking out over the tiny little Jewish stretch of the Roman Empire, couldn't help responding to.

First, the area was caught in the grips of a rogue government. Rome, the empire, was living off the booty of small countries too weak to resist them.

Second, the local poor and outcasts were being ignored.

And third, these satellite peoples faced a future that was being throttled. All the wealth of the area that should have been supporting the locals was going to Rome in the form of taxes.

Yet, in the midst of it, Jesus promises, "Happy are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied."

It was not good time for the area. There were rumblings underneath it all, of course. There were a few protests. But, in toto, it looked like no one really recognized the problems or were able — or willing — to do a thing about it: not the high priests, not the poor themselves, not the local politicians who were on the take from Rome and, thus, disinterested in their own constituents.

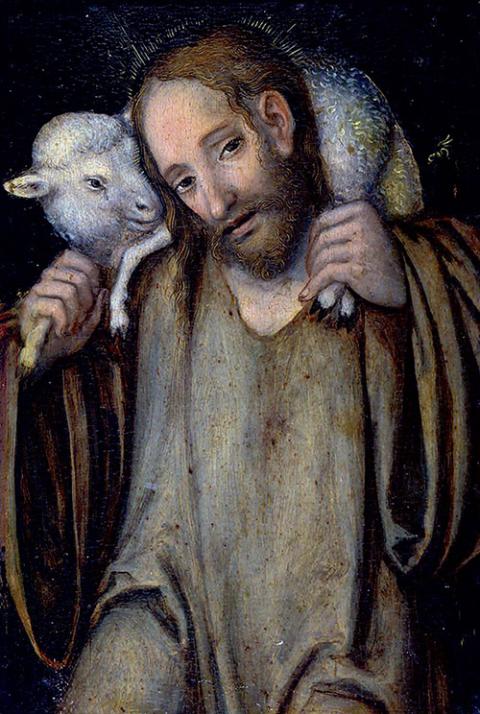

Pope Francis distributed a card with this image of "The Good Shepherd," a painting by the German Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach der Ältere, to Italian bishops during their extraordinary general assembly on "the synodal journey of the church in Italy," Nov. 22 in Rome. On the reverse of the card are "The Beatitudes of the Bishop." (CNS photo/Courtesy of Holy See Press Office)

But all is not lost. Think a bit. Jesus, in the Beatitudes, tells them what to do about it all. "Hunger and thirst for righteousness," he says.

Our question? How?

Did you ever stand near a hot stove and watch water boil? You should; it's an interesting social process. At first sight, it seems as if the water in the pan is so cold it will never heat up. Then, suddenly, there is a bubble or two on the bottom of the pan, closest to the heat. And, suddenly, all at once, where there had been seen to be only disinterest, the steam begins to rise from nowhere and the waters begin to roar and roll.

That, I think, may be happening now, too. I saw two hints as I write this that the country — after years of protests about police brutality, women's equal rights, justice for all — may be beginning to boil over.

In the first instance, a German nun by the name of Sr. Philippa Rath, from a Benedictine monastery in Rüdesheim, Germany, calls for the church, the Vatican, and the pope to begin to recognize the equality of women as well as end the violence against women everywhere. And what's more, she did it on a live podcast. Meaning, she cast her seeds to the wind so they could take root everywhere, (No small public statement by a nun from a monastery founded by St. Hildegard of Bingen in 1165 and restored in 1904.)

Secondly, a Catholic family in Baltimore protested when their teenage daughter was made by the local priest to change her LGBT pride shirt — in public — at the Catholic school she attends. The cause? A spokesman for the archdiocese said, "The attire contained imagery and language with a message that could be determined to oppose teachings of the Catholic Church." The family is now waiting for a public move toward diversity at the church and, the mother says, "an apology would be nice."

What's more, the girls' teenage friends and large numbers of other parishioners rose up to defend her, as well. Small, isolated bubbles, perhaps, but bubbles, nevertheless.

If wearing an emblem that speaks to the humanity, the naturalness, the equality of LGBT people "opposes Catholic teaching," what shall we do about clerical sexual abusers, wife beaters, rapists, tax dodgers, and unvaccinated resisters to bring order to society and real morality to religion?

If we can't wear articles of clothes celebrating the multiple demonstrations of sexual orientation, are we saying that those who — presumably by the action of God's creation — have been born gay do themselves also oppose Catholic teaching? Just by being born? And that says "what" about the Catholic theology of God? Think!

To recoil from that kind of skewed morality is what you call to "hunger and thirst for righteousness." That's when enough is enough. That's when a white jury notes resoundingly that killing a Black man for taking his daily run through a white residential area is in fact murder and a crime.

Advertisement

No doubt about it, we're in a very difficult moral moment in one of the most "morally" defined but confusing governing philosophies in history. Things are happening now that just 10 years ago would have been unheard of, absolutely unacceptable until scientists have to begin to wonder how much pressure the center can stand before it rends itself in two.

Indeed, the fault lines are straining: We elect politicians now with not so much as a nod to moral character before election or after it. We send people to Congress to "cancel" the other party's president, not to pass legislation together that will develop every segment of the country. We talk about equality but wait in vain for the Supreme Court to uphold it.

We promise basic "freedom and justice" for all and maintain that the Bill of Rights belongs to all dimensions of society — except for the ones who don't qualify for it, of course. Like Brown people, Black people, Muslim people, Latino people, female people and those who want gun control in the United States, among others.

Most concerning of all, the very parties and political bodies meant to maintain the moral and civil standards hold themselves and their colleagues to no standards at all. In fact, they themselves are far too frequently the most reprobate, least civil, most cowardly, brazenly silent, and least moral of them all.

A bubbling pot of water is just like that. It takes a long time to boil, but little by little, the isolated bubbles begin to heat, to rise, to roll over the edges of a society playing with notions of insurrection, political dictatorship, public indecency, and organized division.

When will any of them begin to "hunger and thirst for righteousness" again amongst themselves? Not simply the bold and blustering ones but the ones who are so dangerously silent that the rest of the country looks for help and finds nothing and no one who will carry the American flag back to the flagpoles of yesterday. Nothing and no one.

Nothing and no one. Now there is the real problem.

And yet, it is not the impossible for which we seek. On the contrary: World War II wasn't impossible, as unprepared as we were for it. The Civil Rights Act was not impossible, as dead set against it were most of the country at the time. A Catholic president in a Protestant country was not impossible, as dangerous as the idea seemed. A Black president in a white culture was not impossible in a country where Blacks were only about 10% of the entire population at the time.

No, when you and I decide we've had enough of a country, and God forbid, whatever churches, too, that tolerate hate and call it holiness, just as we once accepted the Irish, the Polish, the Japanese — all the "others" that were once among us — we will win again. In our "hunger and thirst for righteousness" we will bubble up, one at a time, boil over together. And then, as Jesus promises us in the Beatitudes, we will all be happy again.