Cardinal George Pell answers a journalist's question during an interview with The Associated Press inside his residence near the Vatican in Rome, Nov. 30, 2020. Pell, who was the most senior Catholic cleric to be convicted of child sex abuse before his convictions were later overturned, has died Tuesday, Jan. 10, 2023, in Rome at age 81. (AP/Gregorio Borgia, File)

The sudden death two years ago of Cardinal George Pell, the Australian prelate Pope Francis had enlisted to clean up the Vatican's finances, left the Catholic conservative cohort in Rome without an identifiable leader. A new biography takes a look at his legacy and how he came to win the pope's trust while speaking for those at odds with a papacy often more concerned with inclusivity than tradition.

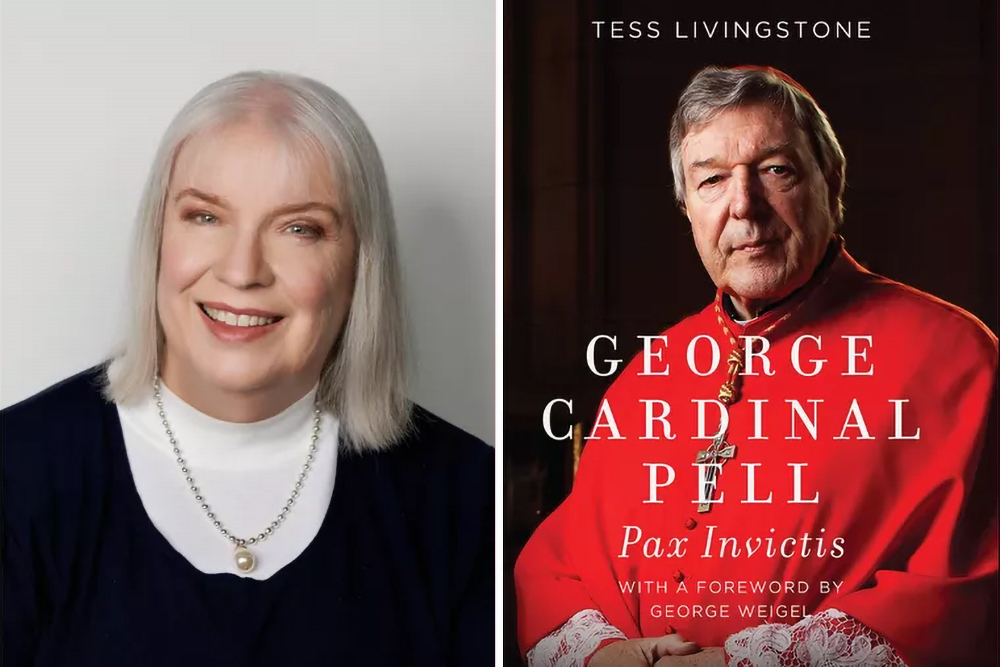

George Cardinal Pell: Pax Invictis, by journalist Tess Livingstone, delves into the remarkable highs and harrowing lows of Pell's life, from his upbringing outside of Melbourne to his growing faith and intellectual curiosity that would earn him the role of archbishop of Melbourne.

It also describes, with a wealth of sources and unreported details, the struggles Pell faced as the Vatican's finance czar, followed by 404 days in an Australian prison after being accused of abuse of minors. Convicted after two trials in 2018, Pell was set free by the Australian Supreme Court after the allegations were proved false.

Advertisement

Pell distinguished himself early on by being an articulate defender of the Catholic faith. "He was not one to mince words," said Livingstone, in an interview with Religion News Service, adding that Pell was often not politically correct when he addressed LGBTQ issues, sexuality and bioethics. He also overhauled Catholic education in Australia and initiated a reform of seminaries, which led to a growth in vocations.

His erudition, coupled with his towering physique, caught the attention of the Vatican, and he was tapped to advise the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith alongside Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI.

In 2003, Pell was made a cardinal by Pope John Paul II and, in his first foray into the complex dynamics and politics of conclaves, supported Benedict's election as pontiff in 2005. Pell emerged as a kingmaker with the influence to point to the future leaders of the Catholic Church and its 1.3 billion followers.

Though Pell supported the Italian Cardinal Angelo Scola in the 2013 papal conclave, he eventually joined forces with other Anglophone prelates who believed that the Argentine Jesuit Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio would be the right man to overcome a storm of sexual and financial scandals.

On his election, Francis named Pell the first Vatican secretary for the economy, charging him with reforming the institution's notoriously corrupt finances "from the ground up," Livingstone said, adding that "this brought a lot of opposition."

Tess Livingstone, author of "George Cardinal Pell: Pax Invictis." (Courtesy of Carmel Communications and Ignatius Press)

There was also no shortage of intrigue and scandal. The Vatican financial auditor, with whom Pell worked closely, Libero Milone, was unceremoniously ousted in 2017 on charges of espionage, which were never proved and were eventually dropped. Pell's efforts to bring in a close adviser and friend, Danny Casey, were met with opposition within the church. Livingstone reports how members of the "old guard" in the Curia viewed Pell as a temporary nuisance to be waited out.

"They don't like Anglo's here," Livingstone said of the primarily Italian- and European-dominated Curia.

Pell was among the first to identify dubious investments by the Vatican's Secretariat of State, under the leadership of Cardinal Angelo Becciu at the time. Becciu would later be accused of money laundering and collaborating in defrauding the Vatican of roughly $375 million. Pell also shed light on the improper use of funds donated for the pope's charitable works, known as Peter's Pence, and of the Vatican's pension fund, which the pope admitted still faces "serious imbalance" in a November 2024 letter to cardinals.

Between sparring with the Curia and uncovering scandals, Pell found himself at odds with Francis, who would sometimes put the brakes on the financial reform and with whom the cardinal did not always see eye-to-eye on doctrinal issues, particularly priestly celibacy and sexuality.

"George Pell, never a fool or a naif, understood that he was walking into a minefield," wrote the conservative Catholic commentator George Weigel, a close friend of Pell's. "He could go slowly and try to get 'buy-in' from the curial recalcitrants, largely Italian. Or he could put the pedal to the floorboard, on the theory that Francis' would be a short pontificate and that the window of opportunity for deep reform could close precipitously," Weigel wrote.

Pell chose the second strategy but was stopped short by the charges and his initial conviction. Held in solitary confinement, he was prevented from saying Mass for more than a year. While imprisoned, he wrote three volumes about his spiritual reflections, called Prison Journal.

The exterior of Domus Australia, a hotel created by Cardinal George Pell to host Australian pilgrims in Rome. (RNS/Claire Giangravé)

After being cleared in 2019, he didn't resume his official duties, but his Vatican apartment, Weigel wrote, was a refuge for those who objected to the direction Francis was taking the church.

Pell died at 81 on Jan. 10, 2023, after hip surgery at the Roman hospital Salvator Mundi. Only a few days earlier, he had attended the funeral of another champion of the conservative Catholic cause, Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI. It was later revealed that Pell had circulated letters he'd written under the pen name Demos, criticizing Francis' leadership and suggesting who should be elected to succeed him.

"Ironically, when he was a young man, his uncle used to write to the local paper under the pen name Demos," Livingstone said. "I believe there are others who contributed to the memo. I think a lot of people felt that way, and they had strong concerns, and they expressed them."

After Pell's death, Francis seemed emboldened to move against other conservatives. Cardinal Raymond Burke, considered a de facto leader of conservative Catholics in the United States, was evicted from his Vatican apartments and his salary was terminated in November 2023.

At the Domus Australia, a hotel created by Pell to host Australian pilgrims in Rome, the loss of the giant Australian prelate is still felt. On Australia Day (Jan. 26), clergy and faithful gathered for a solemn Mass at a church next door, where Cardinal Gerhard Mueller, a German prelate who has also been critical of Francis' papacy, presided.