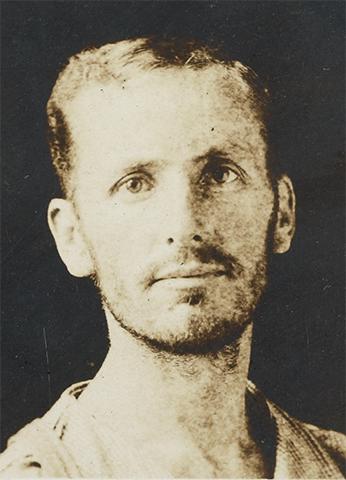

A photo of Ben Salmon from his case file at St. Elizabeths Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., where he was sent by the government during a hunger strike. (National Archives and Records Administration)

An image from 1919 shows various kinds of gas masks used by soldiers in World War I. (Wikimedia Commons)

Clad in oversized goggles, with grotesque face coverings under otherworldly gasmasks, soldiers in the trenches of the First World War seemed fully mechanized, fully dehumanized, in their attempt to survive the world's first employment of chemical warfare on a large scale. The industrial revolution, and the technology that it ushered in, had finally been turned from their original home in industry, to the art of war itself.

You can see the fear-inspiring uniforms the soldiers wore, along with life-size images of men in them, at the National World War I Memorial and Museum, just a few miles from NCR's headquarters in Kansas City. In this year, the centennial anniversary of the war's end, that old technology serves as a ghastly reminder of the ways in which warfare evolved in the 20th century. While World War I changed what war itself could be, it also began a change in how the church, both leadership and laity, thought about war, the United States, and Catholics' role in both.

In Rome, Pope Benedict XV, who reigned from September of 1914 until his death in early 1922, pled the cause of peace, issuing an encyclical decrying war in November and calling for a Christmas truce in December. As the conflict raged on, he continued calling for an end to hostilities and even presented a plan to end the war, although his pronouncements were largely disregarded by the belligerents.

In the U.S., which stayed out of the European conflict until April of 1917, the bishops pledged the support of American Catholics for the war effort as soon as it was underway.

"Moved to the very depths of our hearts by the stirring appeal of the President of the United States, and by the action of our national Congress, we accept whole-heartedly and unreservedly the decree of that legislative authority proclaiming this country to be in a state of war," the bishops wrote to President Woodrow Wilson after the declaration of war.

A photo of Ben Salmon from his case file at St. Elizabeths Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., where he was sent by the government during a hunger strike. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Although the U.S. reaction to the war undermined the papal position at the time, it was hardly unique. "French Catholics saw the war as a chance to unite France; German Catholics (persecuted by the state in the 19th century) participated wholeheartedly," historian and former dean of the University of Notre Dame College of Arts and Letters John T. McGreevy told NCR. "And the same was true for Italian, Belgian Catholics etc. This all made it challenging for the Vatican to manage tensions, especially when Benedict XV offered his own peace plan, and was then challenged by the peace plan offered by Woodrow Wilson."

While many American Catholics shared their bishops' sentiments and served in the war wholeheartedly, some did not. One example was Denver resident Ben Salmon, who refused to go to Europe after being drafted in 1917. Despite the pronouncements of the leadership of his church, Salmon cited his religious convictions in a letter to the president, stating, "The commandment 'Thou shalt not kill' is unconditional and inexorable … When human law conflicts with Divine law, my duty is clear. Conscience, my infallible guide, impels me to tell you that prison, death, or both, are infinitely preferable to joining any branch of the Army."

At the time, it seemed that there may be "no space for someone like Ben Salmon in the Catholic Church," Marie Dennis, co-president of Pax Christi International told NCR. "While in other traditions … there was an agreed upon root for a conscientious objector. That simply didn't exist in the Catholic Church."

Marie Dennis, then-co-president of Pax Christi International, speaks at an event at the United Nations in 2017 (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

The church had long relied on the Just War Theory to determine the morality of participation in such conflict, "which had been useful but didn't stretch the thinking very much beyond that, which was very notable in the United States," Dennis added.

Salmon was sentenced to death for his refusal to participate in the war, but found support for his position among some parts of the church, including Msgr. John Ryan, a moral theologian at the Catholic University of America, who rallied to his defense. Salmon's sentence was ultimately commuted, and he was released in 1920.

While the bishops' letter seems to depart from the condemnation of war that might be more common among Christians today, it is worth noting that, at the time, many Catholics living the country were immigrants, and sometimes suspected of harboring their true loyalty to the pope, and not their country.

"The U.S. church was not considered part of the U.S. political mainstream," Dennis said, and the bishops may have viewed their letter as "an opportunity to raise the status of Catholics in the United States." In this sense, the war was a new beginning for Catholics in the U.S.

The bishops' tone in approaching war would show clear signs of evolution in subsequent decades. In 1983, the bishops conference released a pastoral titled "The Challenge of Peace," in which they acknowledged the long tradition of pacifism in Christianity, saying that "The vision of Christian non-violence is not passive about injustice and the defense of the rights of others; it rather affirms and exemplifies what it means to resist injustice through non-violent methods."

Advertisement

The bishops also noted that, "In the centuries between the fourth century and our own day, the theme of Christian non-violence and Christian pacifism has echoed and re-echoed, sometimes more strongly, sometimes more faintly," and that many great Christian figures took non-violent stands. They point out that St. Francis of Assisi forbid members of his lay orders from taking up arms, and declared their support for conscientious objection to participation in war.

People like Ben Salmon and Francis of Assisi represent the change laity can bring, especially when rooted in the Christian tradition that both lay and ordained in the church are charged with safeguarding. Among Catholics during the war, their attitudes of "nationalism and patriotism [were] a contrast from the 19th century, when the Vatican, especially, issued cautions about glorifying the nation at the expense of families and local communities," McGreevy said.

While both the country and the church have rethought their positions on his decision, a movement is currently underway to gain Salmon the same recognition as Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian conscientious objector who was put to death by the Nazis in 1943 for his stance, and is now just one step away from sainthood.

The Friends of Franz and Ben, an advocacy group seeking recognition for the two men, says on their website that they "are grateful that the Catholic Church recognized the faith, courage and morality of Franz Jägerstätter by bestowing the sacred rite of Beatification on Franz in 2007. Now, it's time to do the same for the American 'unsung hero of the Great War,' Ben Salmon of Denver, Colorado."

The group has been seeking the opening of Salmon's sainthood cause since a meeting with a representative of the Denver Diocese in 2013.

The American church has implicitly acknowledged the admissibility of Salmon's conscientious decision; by opening his sainthood cause it could return the gift he gave the church over 100 years ago: an example of a person willing to engage his national identity with his religious identity, and ultimately arrive at the only conclusion his conscience would accept.

[James Dearie is an NCR Bertelsen intern.]