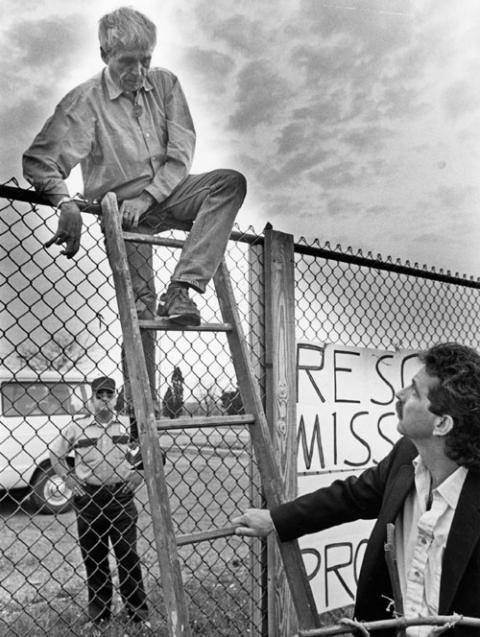

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, in April 1978 (NCR/Leslie Jean-Bart)

The biblical Daniel was not the only Daniel to have spent time in a lions' den and survived to tell the tale. There was also my friend Daniel Berrigan, the troublesome Jesuit priest and poet who spent two years in federal prison for making it more difficult for the American government to send young men to fight in Vietnam, an unjust war if ever there was one.

In pursuit of more lions' dens to visit, Dan had numerous briefer stays in jail in the decades that followed. He was a priest unable to make his peace with war or, indeed, for any sort of intentional killing of human beings, from the child in the womb to those who might be seen as ideal candidates for euthanasia.

Thanks to Catholic Worker co-founder Dorothy Day, we first met in 1961. She brought me with her to a small gathering in Harlem at which Dan read a paper on new winds that were blowing in the Catholic Church, thanks to windows being opened by Pope John XXIII. At the time Dan was a lean, wiry man with closely cropped black hair, dressed in tailored black clericals and a Roman collar, very much the upcoming Jesuit academic.

He was introduced to us as a poet who had won the Lamont Poetry Prize and was currently teaching theology at Le Moyne College, a Jesuit school, where he also had founded an international house at which students were living in community in preparation for mission and justice-oriented work in Latin America.

It wasn't until 1964 that we met again. Dan was on sabbatical and I was one of several Catholic participants in a traveling European seminar headed, via Paris and Rome, to Prague. He was already in Paris when we arrived, living with a group of students at the parish of St. Severin on the Left Bank.

At first sight I didn't recognize him. The tailored clericals and Roman collar had been replaced with a black cotton turtleneck, black chino slacks, a faded green windbreaker jacket, and a suede leather tote bag slung over his shoulder that served as mobile library and wine cellar. The transformation of clothing was less striking than his face. Three years of breakthroughs and setbacks had marked him. In 1961 he had struck me as a well-turned-out cleric taking root in academia like so many up-and-coming Jesuits. Now his once pink face seemed blizzard-worn.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan was arrested in November 1991 for entering Seneca Army Depot in an anti-war protest. (CNS/Courier-Journal/Linda Dow Hayes)

What had brought him, I asked, from Syracuse to Paris? It was due, he said, to his liturgical innovations — saying the Mass in English well before such usage was officially authorized — plus his engagement in the local civil rights movement, irritating donors to the university. These impolitic activities had caused tension between him and the college administration. After six years teaching theology at Le Moyne, Dan had been given a yearlong sabbatical in France. "Was this meant as a sugar-coated exile?" I asked. "Very likely," Dan responded, "but what a place to be!"

Our three-day Parisian stay included street searching, river walking, bread buying and wine sipping plus meetings with several remarkable people, including two "worker priests," plain-clothed men whose mission was among anti-clerical workers in factories rather than pious Catholics rooted in parishes. We also spent several hours with Jean Daniélou, fellow Jesuit and eminent scholar of the early church.

For the French, Vietnam was not far away. The Indochina War had ended with the Battle of Dien Bien Phu only a decade earlier, in May 1954. Paris was crowded with Vietnamese refugees and restaurants. With this David-vs.-Goliath defeat of France, "The end of the Indochinese colonial adventure was at hand," Dan commented. "The republic was stricken at the heart, to a degree it had not known since the German occupation. It was a period of national humiliation and turmoil." During his sabbatical, Dan became one of the relatively few Americans for whom "Vietnam" was a familiar word years before it was of consequence to most Americans.

In a cellar café in Prague 10 days later, the several Catholic participants in the seminar resolved to found, on our return to the U.S., a group we christened the Catholic Peace Fellowship. Our main goal, we decided, would be to organize Catholic opposition to the Vietnam War, then in its early stages as far as America was concerned, and extend a helping hand to Catholic conscientious objectors.

Back in New York, I returned to my newspaper job while Dan was assigned to be one of the editors of Jesuit Missions. "I returned to the United States," Dan later recalled, "convinced of one simple thing — the war in Vietnam could only grow worse. We Americans were about to repeat the already bankrupt experience of the French. I was afflicted with a sense that my life was being truly launched upon mortal and moral events that might indeed overwhelm me, as the tidal violence of world events churned them into an even greater fury. I had a sense that this war would be the making or breaking of my brother Phil and me." At the time Phil was a priest in the Society of St. Joseph.

Six months later — January 1965 — I was working full-time for the Catholic Peace Fellowship. Tom Cornell, another former editor of The Catholic Worker, soon joined me. The three of us normally met once a week in Dan's one-room apartment for Mass, to read letters Catholic Peace Fellowship had received, and to decide on other aspects of our work.

How to respond to the worsening conflict in Vietnam was a factor in every meeting. Catholic Peace Fellowship's work prospered. Before the decadelong war ended in 1975, more than 300,000 copies of a Catholic Peace Fellowship booklet I had written — Catholics and Conscientious Objection — had been sold or given away. We had chapters spread across the country. Increasingly Catholics were judging the war as unjust and immoral.

Dan was of course pleased that our work was having a significant impact in building Catholic opposition to the war, but — with the war getting steadily worse despite widespread protest — by 1968 he and Phil decided it was time not only for opposition but resistance. On May 17, half-a-century ago, the two brothers and seven others burned 378 draft records in a parking lot adjacent to a draft center in a Baltimore suburb. The event was first-page headline news. The Catonsville Nine, as they were known, are still being talked about.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, left, and his brother Philip, lead a peace conference in 1985 at Kirkridge Retreat Center in Stroudberg, Pennsylvania. (NCR/Walter Walden)

Dan was nothing if not a writer. One needs at least a shelf or two for his 60 books of prose and poetry. But the text he is best known for was quite short — a two-page declaration in which he explained what led him to Catonsville. Here are some extracts:

"Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise. For we are sick at heart. Our hearts give us no rest for thinking of the Land of Burning Children. …

"All of us who act against the law turn to the poor of the world, to the Vietnamese, to the victims, to the soldiers who kill and die for the wrong reasons, or for no reason at all, because they were so ordered by the authorities of that public order which is in effect a massive institutionalized disorder. We say: Killing is disorder. Life and gentleness and community and unselfishness are the only order we recognize.

"For the sake of that order we risk our liberty, our good name. … How many … must die before our voices are heard? How many must be tortured, dislocated, starved, maddened? How long must the world's resources be raped in the service of legalized murder? When, at what point, will you say no to this war? We have chosen to say, with the gift of our liberty, if necessary our lives: the violence stops here, the death stops here, the suppression of the truth stops here, this war stops here.

"Redeem the times! The times are inexpressibly evil. Christians pay conscious, indeed religious tribute, to Caesar and Mars, by the approval of overkill tactics, by brinkmanship, by nuclear liturgies, by racism, by support of genocide. They embrace their society with all their heart and abandon the cross. They pay lip service to Christ and military service to the powers of death."

The nine defendants argued in court that attempts to impede an immoral and illegal war — to prevent the commission of war crimes — should be seen as justified, like running a red light to get a gravely injured child to the hospital. Not surprisingly, the court was not open to such arguments. The nine were sentenced to three years confinement but left free for several months while their conviction was being appealed.

During that period of court-authorized freedom, Dan wrote a play based on the trial of the nine. It's something of a modern Greek drama in the tradition of "Antigone." The script has become assigned reading in many classrooms. The play continues to be performed all over the world. It was also made into a film produced by Gregory Peck.

Declining to exit the public square in order to begin serving his sentence as scheduled, Dan went underground. Sheltering in a Sherwood Forest of friends and friends of friends, Dan led the FBI on a Robin Hood-like chase that lasted four months.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, pictured in a 2002 photo in New York (CNS/Bob Roller)

Daniel Berrigan, Jesuit priest, poet and theologian, was placed on the FBI's "Ten Most Wanted" list. In the annals of crime in America, he remains the only person ever promoted to that august rank who never possessed a deadly weapon and posed a threat to no one's life. They should have added a sentence: "This man is disarmed and dangerous."

While in hiding Dan did television and newspaper interviews and even preached in church one Sunday morning. I had a meeting with him one evening in an apartment a short walk from the FBI's Manhattan headquarters. Dan seemed to be available to anyone and everyone except FBI agents. Finally he was found and handcuffed while staying in a hermitage provided by friends on Block Island. Not long afterward he and Phil were on the cover of Time magazine.

Dan, who once described his entire life as an act of protest, was the target of sharp criticism until the day he died, April 30, 2016, age 94, but lived long enough to witness some remarkable validations. Not least he saw a fellow Jesuit with a similar conscience elected pope and take the name Francis, thus linking his pontificate to the poor man of Assisi who became a missionary of mercy and an enemy of war. He lived to hear the same pope stand before both Houses of Congress and single out for praise two of Dan's principal mentors, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

Just months before Dan's heart stopped beating, the Vatican hosted a global meeting of peacemakers who proposed that it was time to bury the "just war" doctrine and focus instead on nonviolent methods of conflict resolution and what makes for a just peace. In all the 16 centuries of the just war theory, it was pointed out at the conference, no national hierarchy had ever condemned as unjust any war its nation's military was engaged in. Dan was one of those who has helped speed the day when Christians, whether Catholic or otherwise, could no longer attach the adjectives "just" or "holy" to the word "war."

Playing in one lions' den after another, throughout his life Dan was a performer and artist but his art was rarely art for art's sake. His was a life of lived-out translations of such biblical commandments as "thou shalt not kill" and "love one another." How sadly rare it is to find a person — Dan was one of the exceptions — who regards such a straightforward mandate as obliging us to protect life rather than destroy it, even if that requires saying a costly "no."

Advertisement

Perhaps his most notable quality was his immense compassion, which guided him one way or another on a daily basis, even late in life when it was a challenge just getting out of bed in the Jesuit infirmary at Fordham University that had become his last home.

I recall Dan using the phrase "outraged love." Many people are driven by rage, which rarely does them or anyone much good and often makes things worse. But outraged love is mainly about love. Dan loved his imperfect church, his not always agreeable Jesuit community. He even loved America. But there is much in all three zones that is outrageous, and Dan was never able to be silent or passive about our betrayals. This could have made him a ranter but the artist side of Dan always found ways to channel his outrage into one or another form of creativity, via poetry or a wide variety of acts of witness. He became one of the most consistent voices of his generation for nonviolent approaches to change and conflict resolution — in that dimension of his life a spiritual child of Day. His commitment to life excluded no one.

Dan remarked of Day, "She lived as if the Gospel were true." The same could be said of Dan. He once said, "If you want to follow Jesus, you had better look good on wood." He didn't mean a Christian had to be a martyr, in the sense of dying for one's faith, but a martyr in the literal meaning of the Greek word µάρτυρ: a witness. Part of that witness, Dan insisted, is refusing to use death as a means of improving the world, still less creating the Kingdom of God.

[Jim Forest's latest book is At Play in the Lions' Den: a biography and memoir of Daniel Berrigan (Orbis). Among his earlier books are biographies of Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. His web site: www.jimandnancyforest.com.]