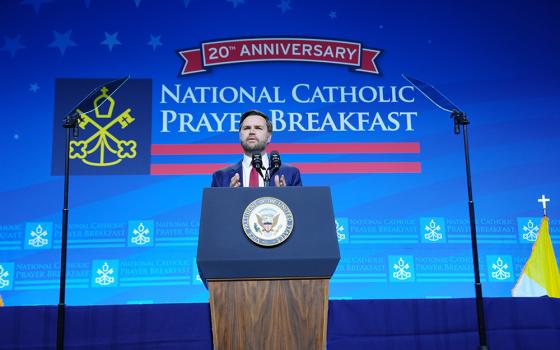

Holy Cross Fr. Stephen Newton, who serves as executive director of the Association of U.S. Catholic Priests, speaks at the podium during the AUSCP's 2022 annual assembly. (Courtesy of AUSCP)

A new initiative by a group representing U.S. Catholic priests to inform clerics of their canonical rights when they are accused of misconduct, including sexual abuse, is attracting criticism from survivor advocates, who say it could help cast accused priests in an overly sympathetic light.

But the clergy behind the effort by the Association of U.S. Catholic Priests, or AUSCP, argue it is necessary. Over the last 20 years, they say, diocesan leaders have failed to respect priests' rights under canon law — in some cases allowing accused clerics to languish in administrative "limbo" for several years while civil and church authorities investigate allegations made against them.

"And in so many cases it's virtually impossible to prove their innocence, because it's pretty hard to prove a negative," Fr. Mike Sullivan, a parish priest in Minnesota who is a canon lawyer and a member of the association's Mutual Support Working Group, told NCR.

That working group, after nearly two years of consulting with bishops, canonists and priests, has crafted a document that delineates clergy members' rights under the Code of Canon Law when accused of wrongdoing, including sexual abuse.

The association is mailing that document, and an accompanying wallet-sized card, to the more than 30,000 diocesan and religious priests in the country who are listed in the Official Catholic Directory.

"We're not taking a position on whether someone is guilty or not guilty. We're saying there's due process, here's what it is, and we will help you access it if you don't get that help from your diocese," said Fr. Stephen Newton, a Holy Cross priest who serves as executive director of the association.

But while they agree that due process is important, clergy sexual abuse survivors and their advocates voice concerns that placing too much emphasis on the plight of accused priests risks a return to the days when the church regularly dismissed victims and protected the priests who abused them.

'No bishop wants to keep in place someone who does turn out to be an abuser of children. The problem is that not every charge is true.'

—Nicholas Cafardi

"I understand the anguish of priests who are wrongly accused and yanked out of a parish without any explanation. But for all of that anguish that they experience, it is minor compared with the pain, the loss and the betrayal experienced by survivors, their families and their parish communities," said Donna Doucette, executive director of the reform group Voice of the Faithful, which was founded in Boston after the 2002 reporting on abuse and cover-up in that archdiocese.

Michael McDonnell, a spokesman for the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, cited research that he said underscores the reality that the ranks of clergy sex abuse survivors outnumber those of falsely-accused priests "by an order of magnitude."

"We recognize that anyone accused of a crime in America has a right to due process," McDonnell told NCR. "We also reaffirm that we believe survivors, and will support those who come forward with allegations of abuse as, far more likely than not, their stories are true."

Priests affiliated with the AUSCP told NCR that they are not looking to deflect attention from survivors or obstruct investigations of clergy sex abuse. They said priests who are convicted of abusing children and vulnerable adults should be held accountable for their crimes.

"I don't try to get guilty priests [acquitted], that's not my job," said Sullivan, one of the founders of Justice for Priests and Deacons, a Las Vegas-based organization that advises clergy members of their canonical rights.

'This will be seen by survivors as special pleading for the people who are in many cases actually the perpetrators.'

—Terence McKiernan

Sullivan and other association leaders said that accused clergy still have rights under canon law, and they suggested that church leaders have often disregarded those rights, especially over the 20 years since the U.S. bishops adopted the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People in June 2002.

"Perhaps the pendulum has gone too far the other way," said Fr. Ed Palumbos, a priest of the Diocese of Rochester, New York, who serves as chairman of the association's Mutual Support Working Group. Palumbos said he believes the Catholic Church in the United States is in the midst of a "course correction" in how it adjudicates clergy sex abuse cases.

"What we find is when guys are accused, falsely or otherwise, they immediately get called into the chancery office, and it's almost a situation where you're guilty until proven innocent, which is the exact opposite of what's fair and just," Palumbos told NCR.

Nicholas Cafardi, a civil and canon lawyer not affiliated with the AUSCP, told NCR that he sees the initiative as "an attempt to bring the pendulum back a little bit more towards the middle, where it should be."

"The problem is priests are being called into the chancery as soon as [an allegation] comes in and before there's been any kind of preliminary investigation. Technically, that's not supposed to happen. The investigation should be made before you take action against the priest," said Cafardi, who suggested that the U.S. Catholic bishops today "are running extremely scared."

"No bishop wants to keep in place someone who does turn out to be an abuser of children," he said. "The problem is that not every charge is true."

That the group is speaking out for the canonical rights of clergy who are accused of sexual abuse presents some unique points of tension for a Catholic organization that is relatively progressive and has collaborated with clergy survivors' groups to advocate for accountability in the church.

"A lot of [association members] are members of our organization. We have a very good relationship," said Doucette, who noted that Voice of the Faithful and the association jointly published a 2019 white paper on clericalism. She told NCR that they groups worked together to gather input during the Synod of Bishops on the Family in 2014 and that they have collaborated on initiatives pertaining to the role of women in the Catholic Church.

Doucette said Voice of the Faithful is not involved with the AUSCP's Rights of Priests project. Doucette added that, as she has in the past, she attended the AUSCP's annual assembly this year. It was held June 20-23 in Linthicum, Maryland, and featured keynote addresses from two bishops: Lexington, Kentucky Bishop John Stowe and Cardinal Peter Turkson, chancellor of the Vatican's Pontifical Academies for Sciences and for Social Sciences.

"I think the fear among the clergy is that the hierarchy doesn't care about whether they did it or not," Doucette said. "[The bishops] just want to make it go away, and the priest will get trampled in the process. It's a problem, and I think you have to look at each instance. There is no easy answer to this."

Newton, the association's executive director, told NCR that the group's initiative is intended to inform priests of their canonical rights. He said the association will support clergy members who feel disoriented and isolated when accused of wrongdoing.

"We can refer [accused priests] to canon lawyers. We can also refer them to civil lawyers if that's appropriate," Newton said. "We don't involve ourselves as an association in the priest's case at all, one way or the other. But we want the person to know what they can do and what works and what doesn't work."

The association's wallet-sized card instructs priests, if they receive an unexpected call from their chancery, to ask for the reason they are asked to report to diocesan headquarters. The card says to "ALWAYS" bring along a "trusted priest friend."

Citing canon law, the card advises priests not to sign anything at the chancery or resign their position, and to have their friend take notes. The accused priest has the right to request that the diocese pay for their canon and civil lawyers, it says. The card also notes that priests have the right to remain silent, and says their friend should ask and answer the questions.

"I mean, I don't want to make it difficult for bishops and dioceses, but if I wanted to remain a priest, it doesn't benefit me to spill my guts," said Sullivan, the canon lawyer who told NCR that diocesan officials often tell accused priests that it will be better for them to be forthcoming.

"So most priests tend to think it's kind of like confession," Sullivan said. "But it's not kept secret, and I'm not sure how [talking] benefits you. The priests don't have to cooperate; that's why they should bring someone along to speak for them."

Advertisement

That may be sound advice from a legal perspective, but from a survivor's point of view, it sounds like a clergy member being given "a license to stonewall," said Terence McKiernan, co-founder and president of BishopAccountability.org.

"This will be seen by survivors as special pleading for the people who are in many cases actually the perpetrators," said McKiernan, who told NCR that the association's initiative risks shielding priests from accountability, regardless of the evidence against them.

"I can understand why quite a few priests — on the left, right and center — feel like they've been thrown out with the bathwater. It's a very challenging environment for them," McKiernan said. "But if you want to fix that environment, do you really want to make it harder to make the church a truly safe place?"

Cafardi said the Code of Canon Law, as written, "is very fair" and allows a diocese to investigate allegations while respecting a priest's rights. The problem, he said, is that the code "is not always followed" and results in situations where priests are effectively in "limbo" while their cases languish for years.

"It's more or less a diocesan prison," said Cafardi, who said he thought an initiative like the AUSCP's should have been done years ago.

"It's only fair that a priest's canonical rights are protected," he said, "just as it's only fair that we listen to victims to determine if their stories are true."