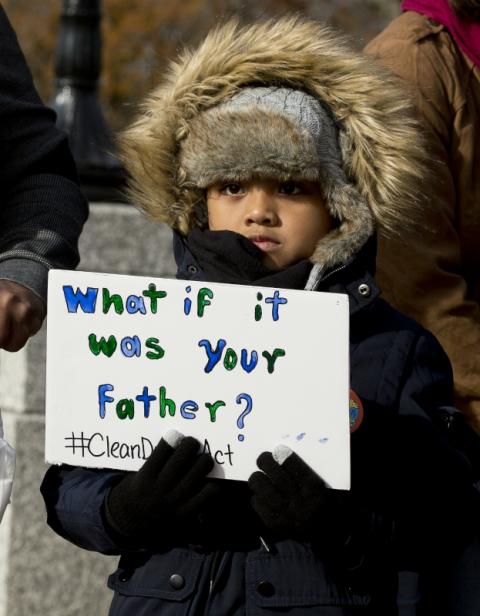

A participant at an immigration rally is seen near the U.S. Capitol in Washington Sept. 26, 2017. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Calls to end "chain migration" often describe endlessly snowballing immigrant populations, caused by laws that allow citizens and lawful permanent residents to bring relatives into the country.

But what some call "chain migration" is also known as family-based immigration, or family reunification. It has been a central component of the U.S. immigration system for more than 50 years, and is a restricted and usually slow-moving process that the U.S. bishops and other Catholic groups have consistently supported.

"The term [chain migration] just misrepresents the reality," said Kevin Appleby, senior director of international migration policy for the Center for Migration Studies. "It's a term that overstates the migration flow coming in, and it also has an undercurrent of discriminating against those of color and people from countries that the president has referred to in derogatory terms."

Family-based petitions are responsible for the majority of immigration to the U.S., around two-thirds of total new green-card holders, but President Donald Trump has called for a shift to a more merit-based immigration system. He even made such change a condition in negotiations to pass a bill protecting undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children, known as Dreamers.

Trump has supported legislation such as the RAISE Act, which would cut total legal immigration; eliminate some family-based categories; and award more visas based on a point system that prioritizes immigrants with advanced degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields, with high-paying job offers, or with millions to invest in the U.S.

"[The Catholic] understanding of migration is rooted in need, not merit," said Julie Hanlon Rubio, professor of Christian ethics at St. Louis University. "In that sense, our obligation of hospitality is an answer to the needs of other people that can't be met in their home countries."

Prioritizing people based on skills they offer the economy would be "a hard sell in Catholic teaching," she said.

In the current system, U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents may file petitions for certain relatives to immigrate as lawful permanent residents; the term "chain migration" refers to the fact that those relatives could in turn petition for their relatives.

However, this "chain" does not form in a rapid or unregulated way. While there are no limits for the admission of U.S. citizens' immediate relatives, defined as spouses, unmarried minor children, and parents of adult citizens, only about 480,000 visas are available for the other relatives that citizens and permanent residents can sponsor.

These categories, which are so backlogged that current wait times for visas range from 2 to 24 years, include siblings and adult children of U.S. citizens and the spouses and unmarried children of permanent residents.

There is no avenue for citizens to sponsor more distant relatives, such as uncles, aunts, cousins and grandparents, or for permanent residents to sponsor siblings or married children.

"Strangers No Longer," a pastoral letter from the U.S. and Mexican bishops in 2003, and a U.S. bishops' summary of the church's position on immigration in 2013 both criticized the long wait times for family-based immigration and listed family-based immigration reform as a major priority.

Advertisement

"The system as it's implemented today is broken because it takes so long to get a family member in," Appleby said. "So when opponents talk about chain migration, they don't mention that it can take a couple of generations to actually get an extended family in."

Prospective family-based immigrants also have to meet certain requirements to be eligible for a visa. They can be barred for past immigration violations, criminal records, certain health issues, or likelihood of becoming a "public charge."

Citizens or permanent residents who file petitions for relatives must prove their ability to support that relative, along with other dependents they may already have in the U.S., at 125 percent of the poverty line.

"It's not really financially ... feasible for most families to be able to bring their entire family to the U.S.," said Jill Marie Bussey, advocacy director for Catholic Legal Immigration Network Inc. "They will live here for years and save up all of their money and then they might be able to bring their spouse and a child."

Many of the immigrants who benefit from family sponsorship come from Asia and Latin America, said Appleby. Opposition to family-based immigration is "really a veiled disguise to limit the diversity of the people coming in. ... The populations that would be hurt are actually large Catholic populations from maybe poorer countries," he said.

Attacks on family immigration are opposed to Catholic teaching that recognizes family as "the core of society," and ignore the social and economic benefits of family-based immigration, Appleby added.

Families "help protect their members, they integrate their members and they start businesses," he said. "Immigrant families aren't static. ... They contribute to the economy and they help create social cohesion in local communities."

Kristin Heyer, a theology professor at Boston College who authored Kinship Across Borders: A Christian Ethic of Immigration, said that in the Catholic tradition, "family relationships are sacred, and in-tact families are vitally important to communities as basic cells of civil society, and 'schools of deeper humanity.' "

Supporters of comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for Dreamers, gather near the U.S. Capitol in Washington Dec. 6, 2017. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

"The separation of immigrant families not only traumatizes members themselves, it also threatens the common good," Heyer wrote in an email to NCR.

While Catholic social teaching does not hold family unity as the "highest value," said Rubio, it does say that heads of households have a right and duty to migrate to support their families and it seems natural not to want to break up families when that happens.

Rubio also said that stories of separated immigrant families show they are "human beings with actual family ties and people who love them." Such stories can be a "way of underlining the more basic idea of why we care about immigrants," she said.

Any policy that separates minor children from their parents would be of special concern from a Catholic perspective, she added.

It is unclear how cuts to family immigration might affect nuclear families, because proposals vary. According to Bussey, suggestions include specifying that Dreamers cannot sponsor their parents; making some reductions as part of comprehensive immigration reform; and eliminating family-based immigration entirely.

"We have to look at what the impact would be on our society for any of these initiatives or proposals," Bussey said, adding that she supports passing a "clean" Dream Act that is not tied to any of these measures.

Appleby, while calling increased funding for border security a reasonable trade-off for the Dream Act, opposed making changes to family-based immigration in order to protect Dreamers.

"Fundamentally altering our legal immigration system, which has been in place for over 50 years, is not a proportional trade for protection for Dreamers," he said. "No matter how deserving the Dreamers are, that would be overpaying the ransom for them."

Appleby added that making some changes to family immigration might be appropriate in the context of comprehensive immigration reform that included a path to legal status for the approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants currently in the country.

"A society is built on the strength of its families, so to abandon that system would really weaken our nation overall," said Appleby. While the details are up for debate, "the basic principle of family unity should be maintained in our immigration system."

"We really believe that we should honor families and they have the right to migrate to support their families," Bussey agreed. "Individuals and families have a right to be together and we're better as a society when families are enabled to care for each other."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]