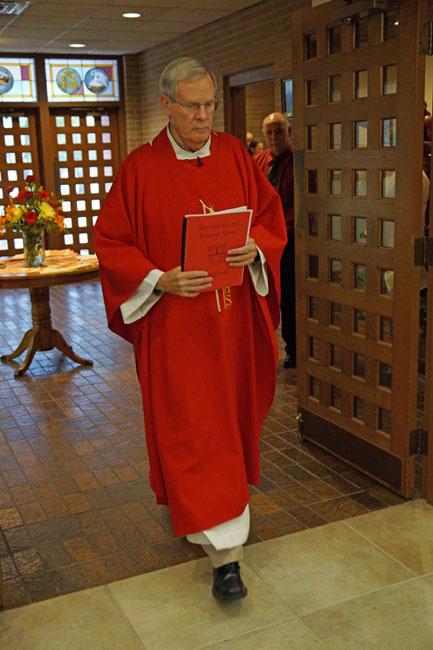

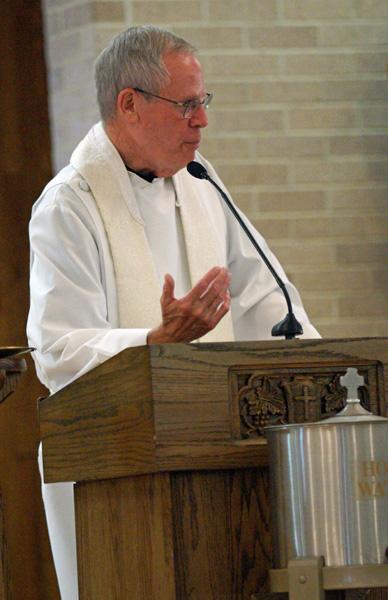

Msgr. Jack Harris at Sacred Heart Church in Morrilton, Arkansas (Courtesy of Sacred Heart Catholic School)

For most people, Arkansas' unprecedented attempt to execute eight men in 11 days in April was a blur of names and stories representative of a larger national debate. For Msgr. Jack Harris, behind each headline was the name and story of a man he has gotten to know.

Few outsiders know Arkansas' death row and its prisoners better than Harris. He has spent the last 14 years quietly ministering to the death row prisoners that occupy the 468 cells in the supermax unit within Varner state prison — a unit Harris describes as a "type of prison they build for those who, well, just have a hard time making it inside the prison system." The isolated unit frequently sees convicted sex offenders, inmates prone to fighting, and all those sentenced to death row.

Harris' dedication to the unit is evident. Twice a week, he drives 122 miles — each way — to Varner, located near Grady, Arkansas, racking up nearly 500 miles a week to visit some of the state's most notorious inmates.

Although Harris — who is pastor of Sacred Heart Church in Morrilton, Arkansas, and St. Joseph Church in Center Ridge, Arkansas — calls corrections ministry "the calling underneath it all," his prison ministry only scratches the surface of his 43 years as a priest. He has served both victims and perpetrators; youth and parishes; and ministered during crises and the mundane.

Prison ministry

"Somewhere I learned the skill, and I guess it's what it is, when you look at a man in prison ... you have to be able to see him and see past what he did. Otherwise you can't do anything with them or for them," Harris told NCR.

This skill, which Harris said he learned early on, is what allows him to look beyond the death of his father.

"There is no such thing as closure. … Nothing brings 'closure.' They love that word, people do. But it's a disappointment, it isn't really there."

— Msgr. Jack Harris

Prior to Harris' birth, his father — a police officer in Little Rock — was murdered in the line of duty. The perpetrator killed himself, leaving the family with no trial or recourse.

"I appreciate having lived on the victim's side of it and watched my family struggle with that," he said. "There is no such thing as closure. … Nothing brings 'closure.' They love that word, people do. But it's a disappointment, it isn't really there."

"Call it the grace of the spirit or whatever," but he has always felt a calling to work with those caught in the correctional system.

"[Correctional ministry] always interested me, for whatever reason, and I can't explain it. It was always there so I'm not surprised that I gravitated toward that after I was ordained," he said.

At the age of 26, Harris was ordained a priest with the Diocese of Little Rock after attending St. Meinrad Seminary in Indiana. One of his first assignments was to teach and work at juvenile detention centers in Little Rock and Pine Bluff, Arkansas. He continued that for the next 22 years.

"I enjoyed teaching and working on the juvenile level. I'd still be doing it if we hadn't run out of pastors," Harris said.

While assigned to the Fort Smith area, he started and built up many programs for youth both outside of and those affected by the prison walls. In 1986, along with the support of three local Catholic parishes, he started Trinity Catholic Junior High in Fort Smith.

Msgr. Jack Harris at Sacred Heart Church in Morrilton, Arkansas (Courtesy of Sacred Heart Catholic School)

One program began by Harris focused on youth involved with the juvenile probation office in Fort Smith. It helped youth pay off fines by performing different jobs, according to Millard Gothard, of Fort Smith, who recalls working with Harris on Saturday mornings "digging up rocks to clear out land for a farm or just clean the grounds at St. Scholastica [Monastery]."

For Gothard, Harris' impact went beyond his assistance with the court system.

Harris would give people business cards with a dime taped to the back to use with a pay phone in case "you need him for any reason or just needed to talk to someone you could call," which Gothard said he used more than once.

Describing his home life, Gothard said he and his siblings pretty much raised themselves from the time he was 5, including finding food or living with no utilities at home. By the time he was 13, he had already had run-ins with the court system.

Harris routinely checked in on Gothard and his family — including visiting him when he ended up in jail.

"For someone like Fr. Harris to show concern where he didn't have to meant a lot at the time … just having someone to talk to that didn't judge my life," Gothard said.

"I just don't think he realizes all the things he's done for me as a young man — from visiting me in jail or just being there when I needed someone. I do believe that God put him into my life to mold me into the man I am today," he wrote in a Facebook post on a fan page started for Harris by former students.

Gothard said he still looks up to Harris as his "role model."

Advertisement

Serving through crisis intervention

By the 1990s, Harris had received his first assignment as a pastor in Jonesboro, Arkansas.

"It used to be that that town would bring instant recognition to people," Harris said.

That recognition stemmed from the March 24, 1998, school shooting at Westside Middle School. Two students shot and killed four students and one teacher. A clinical psychologist at Arkansas State University Jonesboro contacted Harris in the immediate aftermath of the shooting. Aware of Harris' years of working in the juvenile court system, the psychologist suggested he go to a meeting for the school.

"I got pulled into that immediately because of my background with kids and got sent there to the school that afternoon and essentially never left there," he said. "The next five years I was there, I stayed very involved with the school, with that community."

"Just letting them know you really believe in them and are supporting them. That's the key right there."

—Msgr. Jack Harris

Harris' involvement in the community was solidified after he acted as chaplain at a summer camp for students affected by the shooting. In those five years, he worked with over 100 middle schoolers, despite only two being Catholic.

"I started doing for them what I still do for these kids around here [at his current parishes] — they didn't have a ballgame I didn't go to or a band concert or whatever it is they were doing, I would make sure I was there," Harris said.

"Just letting them know you really believe in them and are supporting them. That's the key right there," he said. "That will lead to other things when they need your help specifically, then they may feel like they can approach you. But that relationship is something that has to be earned over a great period of time."

Although Harris has both physically and emotionally moved on from Jonesboro, the school shooting led him to another ministry. In 1998, he received training from the National Organization for Victim Assistance for their Crisis Response Teams.

The training involved five "long" days according to Harris, who said it focused on the "deep study of trauma and what happens to people." As many of the individuals aren't trauma counselors, it was made clear their role was not to diagnose but "to understand the dynamic that you walk into the middle of in a huge crisis."

Msgr. Jack Harris at Sacred Heart Church in Morrilton, Arkansas (Courtesy of Sacred Heart Catholic School)

"We're not mental health professionals, we help them recognize where the help is and hopefully it can encourage them in that direction," he said. "But mostly just give them an opportunity to talk about what happened in a controlled, safe environment."

Harris has been called for group crisis intervention during significant flooding, murders and large storms. He is also involved in training regional teams — so far providing training in 11 different states and in Canada.

"At one point, when I first got involved with this in 1998, there was really only the national team that responded through Washington to individual communities that had these crises happen," Harris said.

"We spent a lot of time training in regions across the country, teams that can handle somewhat locally or regionally these problems, so we don't travel like we did. In a sense, we've worked our way out of a job — wonderful, wonderful."

Death row ministry

Before April, in Harris' 14 years of ministry on death row, only one execution has occurred. During his early years on the unit, he ministered to Eric Nance until his execution on Nov. 28, 2005. That was the last execution to occur in Arkansas — until April 2017.

Though the state set out to execute eight men, it ultimately executed four. Harris was set to accompany four men to their executions, though only witnessed one due to last-minute stays from the courts.

"When we went through 12 years without an execution, maybe all of us began to feel like maybe we can get away from this and stop it," he said. "But once [the state] came back with such harshness that told us all — get ready, get serious, because one day it will, they'll come for you."

NCR first interviewed Harris two weeks after the final execution. He and the inmates were just beginning to acknowledge the loss of what Harris calls "a very significant presence on the row."

"I did not have any idea what it would really be like to go through that two-week process with the buildup and the follow-up of just being down there," he said. "Walking onto the 'row,' the cell block where death row is, knowing there are four men I know very well [who] are no longer there. You're changed by all of that."

The death chamber table is seen in 2010 at the state penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas. (CNS/Courtesy of Jenevieve Robbins, Texas Department of Criminal Justice handout via Reuters)

Harris watched Marcel Williams be executed April 24. "He was one of my men, if you'll pardon the possessive language there," he said. "His absence is very noted." Harris described Williams as "a very strong presence at Mass" who always volunteered for the readings and routinely participated in discussions.

"We're just kind of looking at one another, realizing there was a very significant presence on the row that was no longer there," he said. "We'll settle down but it won't be in exactly the same spot. And I'll just have to see where after such a big movement by the state, just exactly what that will do to us."

While executions typically garner the most news, they play a relatively small role in Harris' prison ministry.

"The actual executions, although they are powerful and they are what get all of the attention, it's a very small part of what you do on the row," he said.

Each Tuesday, Harris walks through the six supermax cell blocks and passes by all 468 cells. His responsibilities vary, sometimes talking to an inmate about sports, other times providing a Bible or sitting and praying with the person.

"They're just happy that someone comes back there and acknowledges that they exist because they are isolated," Harris said.

On Thursdays, he spends his time ministering to the now 29 men on the "row." While there he offers Mass for the Catholic inmates and then goes cell by cell to talk to each of the men (there are currently no women on Arkansas' death row).

"You spend a lot of time with these men when there's no date even in sight. Now it's always on the horizon — we're on death row. … But it isn't what we talk about all the time," he said.

"So it's a lot of time, just a whole lot of time being there, on the row with them.

That's what the ministry is like."

—Msgr. Jack Harris

Conversations often turn to the mundane following church call.

"We'll talk about sports, we'll talk about the food and how horrible it is, visits they've had, we'll just visit," he said. "And many times, the date itself never even comes up."

But that doesn't mean they're not working towards the heavy conversations like how to apologize, how often one must do that and ultimately, salvation.

"What I'm doing is working with these men to assure their salvation," he said. "My belief is that, gosh, if a man is in, whatever way he understands it, confessed his offense to the Lord and asked forgiveness — he's been forgiven. On the other side of that execution chamber are the loving arms of the Lord in heaven."

Part of assuring their salvation includes preparing the men for sacraments. On the row, Harris has performed one baptism (most are already baptized before arriving on death row), three marriages and is currently preparing a couple of men for confirmation.

"All those hours and days, months and years, they all go toward building up to that moment like we unfortunately watched over the past couple weeks," he said after the April executions. "So it's a lot of time, just a whole lot of time being there, on the row with them. That's what the ministry is like. It's just time, lots of it."

Not stopping anytime soon

At 70 years old, Harris continues to maintain all these ministries while presiding as the pastor for two parishes nearly a half-hour from one another.

"It can be a little bit confusing at times trying to balance all of it," he said.

When Harris gets a chance to unwind, he chooses to spend it with the parents and students at his parishes' pre-K through 12th grade school.

"That's what I do when I get out of prison, that's where I head, find a ballgame somewhere, sit in the bleachers, visit with parents, watch kids play, is the most relaxing thing in the world," he said.

"I deeply enjoy being with the students, that's the, I'd say the crown of it all. I really love that," he added.

Unfortunately, Harris' reprieve between executions may soon be ending. On Aug. 25, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced that the state plans to execute Jack Greene Nov. 9 with injection drugs obtained from an unknown source and paid in cash. On Oct. 5, Greene's clemency request — based on the defense's report that doctors had diagnosed him with a psychotic disorder — was denied by the Arkansas Parole Board.

Although Harris and the inmates continue to pick up the pieces, Harris has no intention of stopping or slowing down anytime soon.

"As long as I can walk those cell blocks and climb up those steel stairs and still be able to walk at the end of the day, I'll still be doing it," he said.

[Kristen Whitney Daniels is a freelance writer and former NCR Bertelsen intern.]