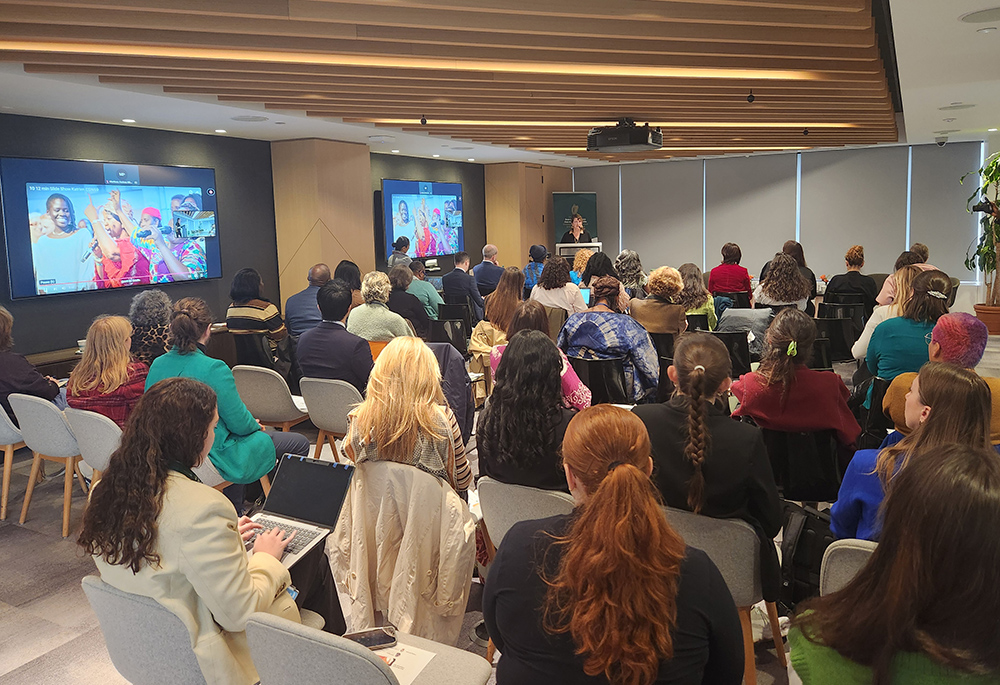

Dozens spoke about gender-based violence during the 69th session of the United Nations' Commission on the Status of Women, held March 10-21 in New York. (GSR graphic/Olivia Bardo)

Editor's note: Today Global Sisters Report launches "Out of the Shadows: Confronting Violence Against Women," a yearlong series on the ways Catholic sisters are responding to this global phenomenon. The series begins with an examination of how the issue has been addressed during the 69th session of the United Nations' Commission on the Status of Women, March 10-21.

(GSR logo/Olivia Bardo)

On Feb. 28, Shiny Kuriakose, a 43-year-old mother, and her two daughters, ages 10 and 11, died by suicide, jumping in front of a moving train near the municipality of Ettumanoor in the southeastern Indian state of Kerala.

The woman had long been the victim of physical and verbal abuse by her husband, her father told Indian media outlet Onmanorama, and her physical injuries even landed her in the hospital.

The outlet said that the mother may have decided to commit suicide after a phone conversation with her husband during which he verbally abused her and said he would not agree to a divorce. The husband, Noby Lukose, was subsequently charged with abetment of suicide.

The tragedy has riveted India. But while the outcome — three deaths — is sadly extreme, what led to it is all too common in India and elsewhere in the world.

"These are the things that happen when so much of patriarchy remains," said Sr. Regy Augustine, a Medical Mission sister whose ministry in Kerala centers on helping women facing challenges from gender-based violence, much of it happening at home.

Indian Medical Mission Srs. Regy Augustine, left, and Babita Kumari, are pictured in front of a Catholic school in Queens, New York City, near where the sisters are staying in a convent while attending the United Nations' 69th session of the Commission on the Status of Women. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Augustine is a private attorney representing women in abuse cases and she also works with four nongovernmental organizations advocating for women experiencing abuse.

"Patriarchal norms and attitudes continue to perpetuate gender inequality and normalize violence against women," she said, adding that "domestic violence is a significant social problem in India, with devastating physical and mental health effects on women, contributing negatively to national and social health."

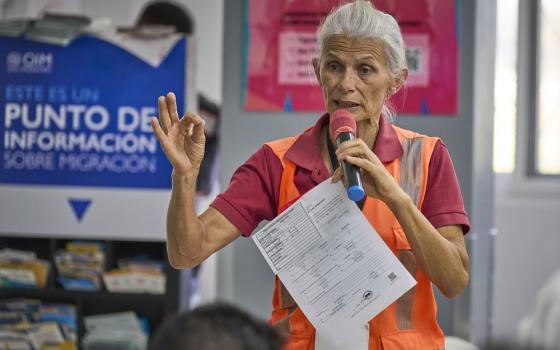

Augustine spoke during the 69th session of the United Nations' Commission on the Status of Women, which focused this year on the 30th anniversary of the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which was adopted by 189 countries and remains a milestone in the quest for gender equality.

Augustine, who spoke during a March 10 event at the Church Center for the United Nations (co-sponsored by four women's congregations), was one of dozens speaking on the issue of gender-based violence during the commission.

The fact that so many sessions during this year's Commission on the Status of Women focused on the issue — with the topic repeatedly coming up even in sessions not focused on that theme specifically — showed the extent to which the problem remains persistent, serious and endemic.

There are, of course, differing types of violence — domestic violence, violence during conflict and war, and online violence targeting women. All were discussed during the commission, but in raising the overall challenge posed by violence against women, speakers noted hopefully that good comes when societies promote gender equality, and that can be a way of reducing gender-based violence.

"We know that societies benefit with gender parity and empowered women," said Adrian Dominican Sr. Patricia McDonald during a March 11 event focused on the importance of women's empowerment. When that happens, McDonald said, societies "tend to have less gender-based violence, including sexual harassment and domestic violence."

There are many layers to unpack, Augustine said at the March 10 event, using India as an example. First is that Indian women are still often seen as inferior to men and "are expected to be subservient to their husbands and other male family members." As society encourages husbands to exercise their rights to control wives, she said, "this mentality leads to a sense of entitlement and control over women."

This dynamic ultimately becomes a "triple burden," she said, because "women who experience domestic violence are often blamed for their own abuse and are told to tolerate it for the sake of their families or marriages."

'Women don't complain; they suffer'

In a subsequent interview with Global Sisters Report, Augustine said that in India, "the institution of family is very precious." That results in comfort, love and security when the family functions well. But when violence becomes a dynamic, harm to women ensues, often masked by silence.

Too often, "women don't complain; they suffer," Augustine said, with some extreme cases ending in suicide, like that of Shiny Kuriakose.

Fellow Medical Mission Sr. Babita Kumari, whose ministry is in Pune, Maharashtra state, India, described gender-based violence as a "crisis," particularly in rural areas where female submission is more culturally accepted and where economic dependence on husbands and male members of families is more prevalent.

A March 20 Commission on the Status of Women event at the Irish Mission to the United Nations focused on gender-based violence and the ways survivors should lead the way to change. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Cultural norms are also more acute — when so much is framed as sacrificing for the sake of family and for children in particular, she said. "The great sacrifice is for the children," Kumari told Global Sisters Report. "Women will say, 'I have a child. Where can I go?' "

Another problem in rural areas: less reporting of violence and abuse to police who, in turn, are far less likely to investigate cases of domestic abuse than authorities in urban areas, Kumari said.

Just prior to the Commission on the Status of Women, UN Women issued a report that took stock of the 30 years since the Beijing Declaration took a larger view. The report noted that 30 years ago, "violence against women was far from mainstream policy agendas," but that the Beijing Platform for Action "recognized the continuum of violence, abuse and harm, which takes multiple forms from rigid gender stereotyping, child marriage and sexual harassment to intimate partner violence and femicide."

A view of the third plenary meeting of the United Nations' 69th session of the Commission on the Status of Women (UN photo/Manuel Elías)

These forms of violence "all have a common root cause: deeply entrenched gender inequality and discriminatory norms," according to the report, echoing what Augustine, Kumari and numerous speakers said at the commission. "The response to violence against women and girls has yet to meet the scale of the problem," particularly in an era described as one of "misogynistic backlash."

There are, of course, new challenges that were unthinkable 20 years ago, the report noted. Digital media have fanned new forms violence, "with bots multiplying the speed and scale of online violence." In addition, generative artificial intelligence “has opened additional spaces to popularize discriminatory stereotypes."

Those new challenges add a new gloss to established patterns — and the patterns, according to UN Women, are sobering, with almost one in three women globally having been victims of some kind of violence. Meanwhile, it is estimated that a woman is killed every 10 minutes, with nearly two-thirds killed by intimate partners or family members, the UN said.

In Haiti, one case of femicide

There is a name for such crimes — femicide — and that, too, became a topic of discussion during the Commission on the Status of Women. One of those addressing that challenge was Catheline Théodora Désiré, a feminist activist and Haitian doctoral student at the University of Miami.

Désiré spoke during a March 13 commission event held at New York University that looked at femicide in the countries of Haiti, Democratic Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast.

Catheline Théodora Désiré (Courtesy photo)

There, she shared the case of Marlene Colin, a nurse who was stabbed 17 times in front of her daughter by her male partner in May of 2018 in Labidou, Haiti, a suburb of the coastal city of Jacmel. Colin was Désiré's cousin but was like an "adoptive mother," Désiré told Global Sisters Report. "She basically raised me and babysat me when I was little."

Fifteen months after the crime, Colin's murderer was eventually convicted and sentenced for the crime — though the sentence was only for 10 years.

Désiré said the murder was traumatizing for her and for Colin's other friends and family. "It's not something I would wish on anyone," she said of the trauma.

But equally traumatizing was coming to realize how desensitized Haitian society was about the case and femicide in general. So much of what was publicly said about the case, including on social media, focused on "what [Colin] 'did to deserve it' and not on the act itself."

What became clear as the case and its reaction unfolded, Désiré said, was the need for a more expansive view: of how greater society, including religious institutions, harm women with the message that it is better to stay in toxic relationships than to risk becoming, for example, a single mother.

"Family councils, religions, authorities, are nonchalant when it comes to violence in couples," Désiré told Global Sisters Report. "They reinforce patriarchy by asking the victim to shrink themselves and stay in the toxic relationship for the children."

Tied up in all of this, Désiré said, are the dynamics of economic dependence.

Even if victims want to leave a relationship, Désiré said, "they second-guess themselves and stay because of the economic shelter that a man provides."

Though speaking of what she experienced in Haiti, Désiré said it is clear that this is a global challenge that needs to become a global cause, both by women but also by male allies and supporters.

"This is not a 'Haitian problem,' " she said. "We are all in danger. This is a global problem."

A woman holds a sign as demonstrators gather Sept. 4, 2019, at the World Economic Forum on Africa in Cape Town during a protest against gender-based violence. (CNS/Reuters/Sumaya Hisham)

Local solutions for a global problem

It is a global problem that must be addressed at the highest levels — like at the United Nations — but also locally, as is being done by a number of sister congregations, including the Medical Mission Sisters.

In the March 11 presentation on gender equality, Kumari took a global view of the sisters' work, noting that integrating gender-based violence awareness and training to health care for poor and marginalized communities has become the norm in a Medical Mission primary health care program in Rubanda, southwestern Uganda.

Notable in that work, she said, is that equal numbers of women and men from 23 villages have participated in trainings to end gender-based violence in local communities.

Such programs can complement progress at national and regional levels. Since the Beijing Declaration, numerous countries have made strides in enacting laws to help boost gender equality.

Advertisement

For example, India has given equal status to women under its constitution, Augustine said, and it has taken some steps to address domestic violence, including passing legislation in 2005 specifically targeting domestic violence.

"But implementation has been inconsistent," she said, quoting an Indian Journal of Medical Research article that points to National Crime Records Bureau statistics that "show that a crime was recorded against women every three minutes. Every hour, at least two women are sexually assaulted and every six hours, a young married woman is beaten to death, burnt or driven to suicide."

While India has made remarkable progress in social development indicators in recent decades, Augustine said, "domestic violence remains a significant impediment to achieving true gender equality, which results in gender-based violence."

Given the seriousness of the problem it is important that institutions — such as government, non-government and religious — redouble efforts to address the problem, including, as Augustine does, working together with such groups.

Both small and large steps help in what Augustine calls "the journey of liberation" for women and the quest for a world in which misogynist violence is reduced and eventually ends.

"Empowering women and stopping violence against them can help the society grow and develop at a faster pace," Augustine said. "A gender equal world is within our reach if we choose it."