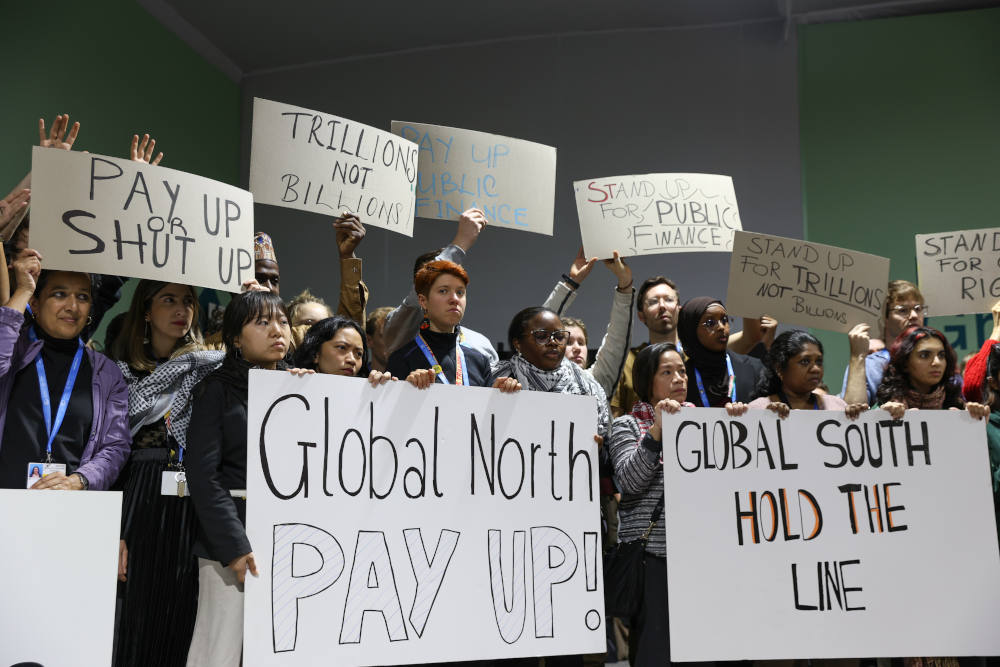

Climate activists hold a demonstration in response to a target for financing climate change responses under negotiation at the United Nations climate change conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan. The summit, called COP29, ultimately struck a deal for $300 billion by 2035 for developing countries. (UN Climate Change/Kiara Worth)

Editor's Note: This story was updated at noon, U.S. central time, with additional reactions.

Catholic organizations at the United Nations climate change summit lambasted a new $300 billion funding target that nations reached over the weekend as too little and lacking guarantees it won't push developing countries further into debt.

Nearly 200 countries at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, agreed in the early hours of Nov. 24 to the new goal for funding to assist developing countries decarbonize their economies and adapt to and recover from climate impacts like worsening storms and droughts. But developing countries, alongside environmental groups and faith leaders, say the $300 billion is far short of the trillions that are needed.

"COP29 has failed to honor its commitments to climate finance, leaving the most vulnerable nations to bear the brunt of a crisis they did not create," Bishop Gerardo Alminaza, vice chairperson of Caritas Philippines, told EarthBeat. "This neglect is not merely a policy oversight but a profound moral failing."

"What we saw at COP29 are baby steps when we need adult strides," said Gina Castillo, climate policy and research adviser with Catholic Relief Services, the overseas development agency of the U.S. Catholic bishops.

The U.N. climate conference in Baku ended more than 30 hours after its scheduled conclusion. The main dispute at the so-called "finance COP" was about money.

Negotiations extended for more than 30 hours beyond the scheduled conclusion of the United Nations climate change conference, known as COP29, in Baku, Azerbaijan. In the end, countries adopted a new target for climate finance of mobilizing $300 billion by 2035 to developing countries. (UN Climate Change/Kiara Worth)

The Paris Agreement required countries this year to replace the prior funding target set in 2009 that sought to secure $100 billion in funding from industrialized countries annually by 2020 for developing countries. That goal was reportedly reached in 2022, though some environmental organizations have questioned how the financing was tallied.

Pope Francis has frequently stated that developed countries, responsible for the vast majority of heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions, have a responsibility to repay the "ecological debt" to other nations, mainly in the Global South, that have contributed the least to climate change but bear some of the worst impacts.

Developing nations at COP29 rallied around an economists' analysis that placed the financing floor at $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 from developed countries if the world is to meet the higher Paris accord goal of limiting average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). Exceeding that limit, scientists say, will result in climate impacts like droughts, extreme storms and heat waves becoming far more severe.

To keep the 1.5 C goal within reach, countries have to slash emissions nearly in half by 2030. Under current climate plans, emissions are set to decline approximately 2.6% by that time.

COP29's final finance text — referred to as the new, collective quantified goal — landed at $300 billion annually by 2035 from developed countries as well as banks and the private sector. The text includes the $1.3 trillion figure, but only recommends financing scales up to that level from public and private sources. It also directs the creation of a road map for raising the additional $1 trillion by next year's climate summit in Brazil.

It is unclear how the $300 billion will be delivered, whether as grants or loans, the latter making up the bulk of climate finance to date. It also does not set specific funding targets for adaptation measures or loss and damage.

"Climate finance is not charity — it is justice and a legal responsibility by the Global North to repay the Global South through public finance mechanisms," said Daughter of Wisdon Sr. Jean Quinn, executive director of UNANIMA International that represents 23 women religious congregations at the U.N. She called the new finance target "a step backward."

CIDSE, the international Catholic development network, said in a statement that without adequate funding it becomes impossible for developing nations to implement vital actions to address climate change, which in turn exacerbate both human and economic costs.

"This COP was marked by developed countries negotiating for their own interests, and not our common good, with vulnerable countries drawn into a bargain they have no choice but to accept," said Lydia Machaka, CIDSE energy and extractivism policy officer.

David Munene, a co-facilitator of the newly formed Network of Catholic Climate and Environment Actors and programs manager at the Catholic Youth Network on Environmental Sustainability in Africa, said COP29 failed to meet his low expectations for new financing.

"A bad deal would have been in the tune of $800 billion. This is a horrible deal," Munene said of the $300 billion target.

"It's like throwing peanuts at a very hungry person in the hope that they will chew on them and regain their strength, which will not happen," he told EarthBeat.

The U.S., European Union and other developed countries pressed for China, Saudi Arabia and other large economies classified as developing nations under the U.N. to be required to contribute to the new target. In the end, the finance text only "encourages" them to do so on a voluntary basis.

Advertisement

Negotiations at COP29 were tense, and described by Catholic officials at different points as slow-paced and chaotic. Delegates for small-island states and least-developed countries temporarily walked out Nov. 23 in protest of the finance talks. Food eventually ran out at the venue site, Baku Stadium.

Azerbaijan ecology minister and COP29 president Mukhtar Babayev gaveled the finance target into adoption before opposition could be raised. India immediately raised objections. Delegates from Bolivia and Nigeria joined in protesting.

Alminaza said that each year vulnerable communities in his home country and across the world "lose their lives and loved ones from intensifying impacts of the climate crisis, not counting the immense biodiversity loss."

"The final text is cruel, placing a price tag of 'at least' $300 billion annually on this suffering," he said in a text message.

Catholic officials also criticized the finance target for not specifying funding for adaptation and the Loss and Damage Fund, the latter which currently relies on voluntary contributions, and for not ensuring new financing comes as grants and not loans.

"This will lead to vulnerable countries going into greater debt to properly prepare themselves, or fail to adapt and face the consequences," said Damian Spruce, advocacy associate director with Caritas Australia.

During COP29, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Vatican secretary of state, delivered a message from the pope urging wealthy nations to forgive debts of other countries for the upcoming 2025 jubilee year.

The U.N. summit did not address a transition away from fossil fuels — the primary source of global warming — that countries acknowledged for the first time in U.N. talks last year at COP28 in Dubai. News reports indicated Saudi Arabian delegates worked to block any references in the COP29 texts.

Countries are expected to align their new national climate plans, due in February, with the COP28 commitment to move away from fossil fuels.

Since the late 1800s, the planet has heated 1.1 to 1.2 C and is on pace to surpass 1.5 C sometime in the 2030s. The latest U.N emissions gap report estimated temperatures will rise between 2.6 C and 3.1 C by the end of the century, but that could be lowered to 1.9 C if all countries' current climate plans and pledges were fully implemented.

Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, waves a copy of the Paris Agreement as he addresses the closing plenary of COP29 on Nov. 24 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (UN Climate Change/Lucia Vasquez-Tumi)

Nations in Baku did finalize a carbon market under the U.N. where countries can trade carbon emissions credits. The decision includes methods for authorizing and tracking credits, as well as mandatory checks on projects to protect environmental and human rights.

Iyo said the inclusion of Indigenous peoples and local communities in decision-making on carbon markets was a step in the right direction. But the potential for "greenwashing" will demand careful scrutiny.

"It remains to be seen whether the carbon markets will deliver on their promises without exploitation or mismanagement," he said.

Countries also agreed to transparency tools around national climate actions, extended a program around climate and gender, and provided additional guidance on climate resilience and adaptation.

Quinn said while slow progress is being made in actualizing the Paris Agreement, she echoed the pope in Laudate Deum in viewing the COP process as "in serious need of reform and transformation," including a greater space in decision-making for women, who are disproportionately impacted and displaced by climate-related disasters.

COP29 was the second to host a faith pavilion, where a Global Alliance for Women Religious Leaders was launched to mobilize and elevate the influence of female faith leaders on climate issues.

Throughout COP29, a pall hung over the proceedings from the U.S. election of Donald Trump, who has stated he will again withdraw the United States — the world's largest economy and largest historical emitter — from the Paris Agreement.

In comments at the closing plenary, Wopke Hoekstra, the EU climate action commissioner, stated, "We are living in a time of truly challenging geopolitics," and referred to the finance goal as realistic and achievable.

Ben Wilson, public engagement director of the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, said countries cannot use Trump's pending return to the White House as an excuse for not meeting the $1.3 trillion funding figure, as they have known for years a new goal would be set in 2024. He added that countries have shown the ability to quickly mobilize financing to bail out banks, respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and wage wars.

"It is a political choice not to invest in climate action in the same way, and I'm afraid our leaders are making the wrong choice," he said.

COP30, the next United Nations climate conference, is scheduled for Belém, Brazil, in November 2025. (UN Climate Change/Kamran Guliyev)

COP30 will be held in the city of Belém in the Brazilian Amazon amid the 10-year anniversary of Francis' landmark encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home."

Catholic officials hope the alignment of the Laudato Si' anniversary and the Amazon setting will lead to more substantial commitments around slashing emissions and boosting financing, especially from wealthy countries in the Global North. Rodne Galicha, executive director of Living Laudato Si' Philippines, said that setbacks at COP29 call on Catholics to commit all the more to work on behalf of the most vulnerable, and for all people of faith "to be the conscience of this complex process."

Added Alminaza, the bishop of San Carlos, Philippines, "It is high time that we make money work not for the destruction of our common home, but for its protection and the dignity of human life."