A view from the stage for Earth Day April 22, 1970, in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. An estimated 20,000 to 40,000 people attended the event, part of the city's Earth Week. (1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia)

It was a cloudy day. There was a chill in the air that Wednesday in spring on the campus of Sacred Heart University, in Fairfield, Connecticut.

In an open green space, members of the campus ministry team set up a stage for a daylong festival. Students with long hair danced in the field. Others sang and played music on stage. A priest led prayers as part of a liturgy for the natural world. There was food, banners and balloons.

The date was April 22, 1970.

The first Earth Day.

"It was a great day. It was full of vitality and song," said Notre Dame Sr. Kathleen Deignan.

(NCR graphic/Jesse Remedios and Toni-Ann Ortiz)

The thousands of celebrations, demonstrations and teach-ins that took place across the American map that day 50 years ago are largely credited with the birth of the modern environmental movement. Those first seeds of ecological concern were planted in national upheaval as the protests against the Vietnam War reached a fevered pitch, the civil rights movement rolled into a third decade, and the nation worried about the buildup of nuclear arms amid the Cold War. The crew of the ill-fated Apollo 13 space mission had just returned to Earth. Within the Catholic Church, the documents of the Second Vatican Council were beginning to take root.

The idea for the first Earth Day is largely credited to Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, who sought to fuse the energy of the student anti-war movement with heightening concern about polluted water and skies. A major oil spill a year earlier off the coast of Southern California, along with Rachel Carson's seminal text Silent Spring published nearly a decade earlier, remained fresh in the minds of many.

A Girl Scout in a canoe picks trash out of the Potomac River during Earth Week in April 1970. (Library of Congress/Thomas J. O'Halloran)

An estimated 20 million Americans took part in that first Earth Day, representing at the time one-tenth of the U.S. population. Scattered among them were many Catholics and people of faith. The staff coordinating Earth Day encouraged local organizers to reach out to the faith community, well aware of the "huge role" they played in launching the civil rights and anti-war movements, recalled Denis Hayes, who was in 1970 the 25-year-old Harvard graduate student Nelson appointed as national organizer.

"I'm confident lots of priests gave Earth Day talks," he said.

In San Francisco, 25 U.S. bishops gathered for their semiannual assembly, concelebrated a Mass for Earth Day, "petitioning that the earth's resources would be used properly," according to a Catholic News Service report from the time.

Prayer services, teach-ins and demonstrations took place on some of the nation's most well-known Catholic campuses, as well as in school buildings in small towns situated among ranchlands and coasts.

These are some of their stories.

At Sacred Heart, the overcast skies weren't enough to blot out the excitement beaming from Deignan. A student and newly professed sister with the Congregation of Notre Dame, she was among the cohort of peer ministers on the campus ministry team, led by Fr. John Giuliani, that planned the open field prayer service that accompanied teach-ins happening elsewhere on campus.

"We wanted to bless it in our own way, in our liturgical way," said Deignan, now 50 years later, the leader and namesake of the Institute for Earth and Spirit at Iona College in New Rochelle, New York.

The convergence of the energy of Vietnam protests and the spirit of Vatican II made for complex but creative times at the Connecticut school. Students joined the nationwide moratorium demonstrations calling for an end to the war. The campus ministry team was exploring new music and new liturgy.

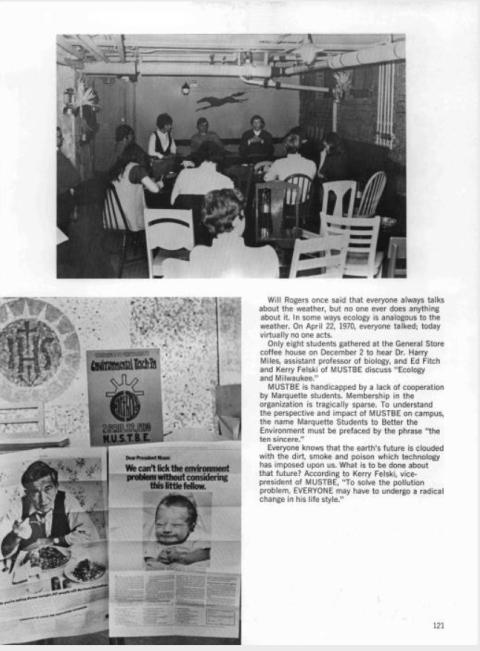

Fr. John Giuliani and Sr. Kathleen Deignan appear on stage during an outdoor liturgical service at Sacred Heart University for the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. (Courtesy of Kathleen Deignan)

"We were kind of riding these winds, these winds from different directions that were blowing throughout the culture and the world," Deignan said, calling it a time "when students were trying to figure out how do we live now."

The Earth Day service was meant to both celebrate creation while also awakening to the crisis facing the environment. With climate change not yet in the vernacular, concerns focused on acid rain, pesticides, polluted water and streams, and the destruction of the atmosphere and ozone layer.

Giuliani, who would later go on to found the Benedictine Grange community, preached from the stage. Drawing on the writings of the late Jesuit Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, whose work was coming into prominence, and Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton, who had died two years earlier, Giuliani delivered an impassioned sermon about the sacredness of the Earth and how all atomic particles in the universe flow from a divine source.

Deignan took to the stage, too. The future composer performed music in a setting just a two-hour drive from the site where Woodstock had played out eight months earlier.

"We looked like hippies, by the way. But that was the way it was in those days. Everybody has long hair and I wore a long skirt," she said, the sister quick to note she did not attend Woodstock.

The news of a nationwide day dedicated to celebrating the Earth left Deignan feeling "really happy, and in a sense, exhilarated."

A self-described urban child of Irish immigrant parents, she said her awakening to the environmental crisis came at St. Jean Baptiste High School in New York City. One day during the lunch period, she was dancing with friends when Mother St. Bertrand called her over and handed her a book, saying "I know this is going to be an important book for you."

"We wanted to bless it in our own way," said Notre Dame Sr. Kathleen Deignan, who helped plan a liturgical service for Earth Day in 1970 at Sacred Heart University. (Sacred Heart University)

It was Silent Spring. The gift from the biology teacher confounded Deignan, who preferred literature and history over science.

"Ever since that day, my life changed," she said. "And the direction of my life changed, and it was clear that this little urbanite was going to ... I mean, we all thought we were going to save the world in the 1960s and '70s, but my part of the world that I would save was the natural world."

As she entered into teaching herself, the Notre Dame sister continued to celebrate Earth Day. One year, she and her class painted a mural. More recently, she has joined her students at Iona in climate marches and protests. Along with founding the Institute for Earth and Spirit, she formed the Thomas Berry Forum for Ecological Dialogue and teaches courses on religion and the natural world.

"That first Earth Day was a seed that I've nourished, for sure."

Just 150 miles to the south, a 17-year-old Teresa Redder was boarding a train with classmates in her hometown of Camden, New Jersey, heading to Philadelphia for the city's Earth Day festivities.

Redder, too, was moved by Silent Spring, part of the assigned reading in her sophomore biology class that oriented her toward environmental awareness. Now a secular Franciscan along with her husband, she recalled sitting on her grandfather's porch and not being able to see the Philadelphia skyline just miles across the Delaware River. The smog and pollution led some residents to refer to the city as "Filthadelphia."

The climate of so many movements captured her attention. Redder sensed the upcoming Earth Day was something major — momentous enough to compel her to skip classes that day at St. Joseph High School and head to Philadelphia, something she still holds some guilt about doing.

Teresa Redder was a junior at St. Joseph High School, in Camden, New Jersey, when she attended Earth Week festivities in Philadelphia. (Courtesy of Teresa Redder)

"It was a really wonderful day," she said.

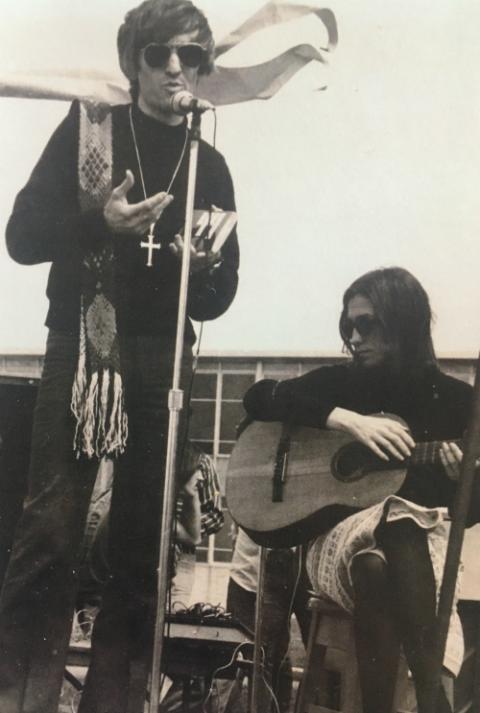

According to estimates, 20,000-40,0000 people descended on Fairmount Park. Songs from the hit Broadway musical "Hair" were sung and others carried themes of pollution, landfills and clean water. Native American themes about caring for the land were prominent. U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie addressed the crowd.

The Earth Day event was the culmination of Earth Week in Philadelphia, one of the largest demonstrations in the country. Student organizers planned the week to pressure city leaders and businesses to combat the air and water pollution from its power plants and chemical plants, oil refineries and incinerators. Demonstrators in gas masks passed out clean water and surgical masks, and displays were built downtown.

A CBS News hourlong report on Earth Day in America, anchored by Walter Cronkite, chronicled the Philadelphia students' efforts to make inroads not only with local businesses and politicians but also to build a diverse coalition. The broadcast noted that the crowd in Fairmount Park was mainly made up of white, middle-class young people.

Efforts to reach out to black community leaders were mostly unsuccessful. Leaders expressed concerns to the students that attention on the environment would take energy away from the anti-war and civil rights pushes. Others didn't see a place for them in a movement to protect streams and wildlife as they continued to deal with voting rights, dilapidated buildings and neglected neighborhoods — some within blocks of the polluting refineries and industrial plants.

"I don't think we are really committed to get involved in Earth Week up to our necks," Herman Wrice, a member of the Young Great Society, told CBS News. "Because, see, we still have hungry children to feed and we still have houses to try to build. ... We really don't have a part in this, because the polluted streams that they're talking about, we've never seen anyway. The trout, I don't know if they're dying, we've never seen that. I know the rats are bigger here. If we mean polluted sewers, I'm ready to play with that."

During a speech in Berkeley, California, Nelson, the senator who initiated Earth Day, said: "Protecting the environment and restoring the quality of American life is going to mean meeting the problems of the ghetto as much as it means clean air and water."

The Rev. Paul Hetrich, then senior pastor at Salem Zion United Church of Christ, remembers the tension among the burgeoning environmental and established civil rights movements at the time. Through the Philadelphia Council of Churches, he worked with other faith leaders, including the Rev. Leon Sullivan of the Zion Baptist Church and Catholic Auxiliary Bishop John Graham, to try to bridge the two sides.

Hetrich, at age 86 now retired and living outside Reading, recalled that he drove most days to the city's hospitals, passing the communities of South Philadelphia living near the refineries along the Delaware River that belched out soot and smoke. The uneven distribution and impact of pollution was part of the dialogues his community at Salem Zion had begun in the years before Earth Day.

The logo for Earth Week 1970 in Philadelphia (1970 Earth Week Committee of Philadelphia)

Those conversations, which at times included Sullivan's Zion Baptist church, focused on pushing back against dominion theology and the distorted view prevalent post-World War II that economic progress and God's blessing were synonymous. In 1967, historian Lynn White had penned his controversial essay "The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis" that argued Christianity and religion, emphasizing dominion over nature, was largely at the root of environmental destruction.

"Theologically we wrestled with that," Hetrich said. "And what do we do about the majority of God's people who don't feel that way and certainly couldn't feel that way with what was happening to them, even in the environment, where they were the ones who are living alongside of the smelters, alongside of the oil companies, the refineries?"

That theme guided the sermon he delivered during Earth Week — what he described, looking back, as "pretty stiff. And in a sense somewhat radical." It was included in the CBS News report:

The church also is involved in Earth Week because some of its poor theology has helped to cause the ecological imbalance that we are facing in nature today. We have always, for the last several hundred years, addressed ourselves to the theme of progress as a theological principle. And we have believed and affirmed that those people who do progress, God certainly is blessing. And because we have progressed and not thought about the ways, the methods that we were using in order to progress, to grow into our technological expertise, we have plundered, we have raped, we have begun to lay the Earth in desolation.

In prayers of contrition, the congregation asked God's forgiveness for fouling the air, polluting streams and cluttering the land with trash, saying, "Now our hearts are heavy with sorrow for what we have done. But not before our sinuses and lungs warned us of great dangers, and our eyes told us that some of the beauty has gone out of your Earth."

Today, the Sankofa Community Farm at Bartram's Garden is situated in the heart of the south Philadelphia neighborhoods adjacent to the refineries. When its farm co-director Christopher Bolden-Newsome speaks with elders in the predominantly black community, no one can recall that first Earth Day, much less that it's preparing to mark a half century.

Christopher Bolden-Newsome leads a group at the Sankofa Community Farm at Bartram's Garden. (Sankofa Community Farm)

Bolden-Newsome said the reason is simple: "It wasn't geared toward us." Born in 1977 a day before that year's Earth Day, he said he felt that black people have long been "afterthoughts" in the environmental movement. Its shortcomings are noticeable, he added, in his neighborhood's health statistics, including higher rates of asthma and lead exposure, more toxic soil and abandoned buildings.

What progress has been made, such as the presence of his farm and others across the city run by people of color that offer their neighborhoods healthy food as well as open and accessible green spaces, isn't because of the mainstream environmental movement. The 50th Earth Day offers a chance for "an honest reckoning," the 43-year-old Catholic said, to address why environmental groups haven't been more successful in engaging people of color.

A second step is recognizing that environmental issues aren't just those threatening some distant nature but "everyday issues" impacting people's daily lives, and, as Pope Francis laid out in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," the connections between environmental destruction and social oppression.

"That you can't separate issues of justice, of human justice from the environment," Bolden-Newsome said.

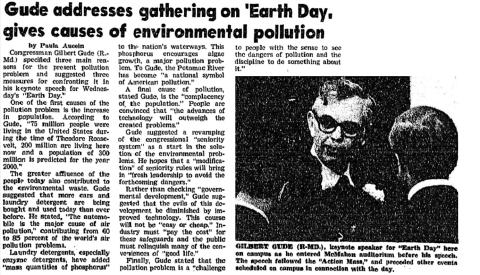

In many parts of the country, the initial Earth Day celebrations centered on college campuses, including numerous Catholic schools. At the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, a series of speakers addressed the campus, including keynote Garrett De Bell, editor of The Environmental Handbook, which was prepared for the national environmental teach-in.

A report in The Tower, the student newspaper at Catholic University of America, recounts the celebration on the campus of the first Earth Day in 1970. (Catholic University of America)

In Washington, D.C., about 400 students attended an outdoor "Action Mass" at Catholic University of America, according to a Catholic News Service report. They filled a coffin in front of the altar with empty soda cans and plastic bleach bottles as young women tossed fresh spring flowers to those gathered. The ensuing teach-in delved into philosophical and moral attitudes on the environment, and explored cleaning up the environment from the perspectives of politics, law, economics and science.

At a rally of 10,000 people near the Washington Monument, a Georgetown University student told CNS that cleaning up the environment would require changes to the economy and the ways that goods are produced, distributed and consumed: "If we are going to breathe clean air and drink clean water, if we are going to survive, we're going to have to make some sacrifices."

At Marquette University in Milwaukee, students planned an all-day teach-in, beginning with a Mass for the Earth. Jesuit Fr. Robert Doran was among the officiants. The Mass was featured the next morning on the front page of the Milwaukee Sentinel.

"It's hard to believe it was 50 years ago," the priest recalled recently.

Jesuit Fr. Quentin Quesnell, center, leads the Mass for the Earth at Marquette University on the first Earth Day. Pictured on the far right is Jesuit Fr. Robert Doran. (Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries)

Doran and the other priests placed plants, soil and a globe on the altar for the Mass. The student yearbook reported that the Mass was moved from a campus chapel to the student union "to accommodate an overflow crowd."

The Earth Day liturgy was planned by the fledgling campus ministry program, which debuted in full that fall with then-31-year-old Doran, ordained just the year before, as director.

Doran told EarthBeat that Catholic theology on creation was still developing at that time. It wouldn't be until the end of the decade that St. Francis of Assisi was named the patron saint of ecology. Seeing students engaged on social issues, he felt it was important that the school also become involved in environmental concerns.

"I knew we had to do something. I knew it was serious and it was also something that I wanted to learn more about," Doran said.

The Earth Day itinerary, planned by the Marquette University Students to Better the Environment (MUSTBE), stretched from 8 a.m. to past 10 that night. Two dozen panels were held, ranging from understanding pollution and the science and theology of ecology, to debates around birth control and abortion. Students planning to attend the Earth Day rally in MacArthur Square were encouraged to use nonpolluting modes of travel.

Diane Phaneuf moves to Marquette University in 1969. (Courtesy of Diane Phaneuf)

The day "felt like a birthday for the Earth," said Diane Phaneuf, a freshman at the time. Growing up on a farm in northwestern Minnesota instilled in her an appreciation for nature, but Earth Day raised environmental issues for her in a new way. The second oldest of nine kids, Phaneuf remembers her jaw dropping during a conversation about population control. The subject was prevalent at other teach-ins across the country, and raised to the level where the U.S. bishops made clear their opposition to population control as a means to reduce pollution.

Phaneuf remembers coming away from the day at Marquette with a feeling "that there's more to life than just living your own life. ... So it was sort of an awakening to human activities' effects which can be detrimental to the health of the Earth."

Like so many other college campuses, Marquette was rocked by anti-war protests. Just 12 days after Earth Day, four students were killed and nine more injured at Kent State University at a protest of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. In solidarity with those killed, students at Marquette held sit-ins and a strike that forced the Jesuit campus to end its semester weeks early.

Descriptions of the first Earth Day in the Marquette yearbook carried a cynical tone. They described MUSTBE as a group of "ten sincere" students who struggled to grab the attention of the campus beyond the teach-in. By the following December, the yearbook staff noted just eight students attended a biology professor's talk on the local ecology.

For Phaneuf, the impact of that first Earth Day still resonates, with messages from Pope Francis only strengthening the call to take better care of creation. "Every time there's an Earth Day, I'd say you know what, I was in on the first one and I heard speakers and I opened my eyes."

After a pause, she added, "I'm going to go plant some seeds right now."

The scene at John A. Coleman Catholic High School, outside Kingston, New York, on that first Earth Day is a memory Sr. Carol Perry will never forget.

The principal knew a committee of students were developing a program, but nothing more than that. As the first school bell was set to ring the morning of April 22, she noticed the building was strangely quiet. She went outside to investigate, finding the parking lot vacant of any school buses or cars or students. That's when she heard "a murmur from afar," and saw in the distance the full 200-student body approaching by foot and bike, by skates and scooters, with one student leading the pack by horse.

"It was unforgettable," said Perry, a member of the Society of the Sisters of St. Ursula of the Blessed Virgin.

Carol Thornton also remembered riding her bike 5 miles that morning with a friend to Our Lady of Victory Academy in Dobbs Ferry, New York. Paul O'Donnell, a first-year teacher at a public school in Providence, Rhode Island, led his sixth-grade class in discussions and art projects focused on the environment as well as clean-up sessions collecting trash around the school and its neighborhood.

Advertisement

For Mary Jo Dawe, news of something called Earth Day led her to immediately begin brainstorming plans for her sixth- and seventh-grade classes at Sacred Heart Elementary School that might make an impact in the tiny, rural Montana town of Glendive. Located in a dry part of ranching country near the North Dakota border, ecology was barely on anyone's radar in the conservative town.

So Dawe, then a Sister of Humility, decided to lead the students on a 15-mile walk outside of town.

"I had learned enough about the Earth movement, so to speak, Earth Day, that made me think that it really made sense," she said. "And that if I could get these students to start questioning and to open their minds to different possibilities, that was an important responsibility I had."

The walk led the students alongside a highway out of town and then wound back into town. While most students finished around noon, the seemingly simple event proved more grueling for Dawe, who struggled but ultimately completed the last several blocks. But the walk accomplished its goal of raising awareness, as the students were featured in the local newspaper.

Back in the classroom, Dawe and other teachers weaved lessons linking Scripture to creation and stewardship throughout the school year.

"I think that first Earth Day was really a spark lighting the awareness of a couple generations," she said.

In Rochester, New York, Sr. Anne Curtis, then a senior at Cardinal Mooney High School, and a half-dozen friends got the OK from their parents to skip school and attend the teach-in at the Rochester Institute of Technology. She doesn't remember much of the day beyond "this overall sense of just being really energized by the experience." Today, she is executive director of the Mercy Ecology, which operates an eco-spirituality center in Vermont.

Oil is seen piled up against a seawall near Santa Barbara Harbor in California following the February 1969 oil spill from a Union Oil drilling platform. At the time, it was the largest oil spill in U.S. history, and helped prompt the first Earth Day a year later. (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Geological Survey)

"It really marked me in a sense of feeling a responsibility for what was happening to the Earth. And beyond my own personal life, that our behavior, our impact was having a negative impact on Earth," she said.

The impact of Earth Day 1970 still reverberates for Diane Bader, too. Her family in Los Altos, California, made an aluminum can crusher and started a composting bin. Her son came home from the school's activities determined to dedicate his life to protecting the Earth. Today, he's the energy manager for a Northern California hospital system that's installing solar panels, while his eldest sister is a park ranger at Yosemite National Park.

Down the coast, the honors society at Mission Catholic High School in San Luis Obispo held a schoolwide assembly with skits, music and a presentation on how environmental concern relates to Scripture. Angela Taylor, their moderator, most remembers the big banners they hung from the auditorium choir loft spelling out "Earth," and each letter depicting a different scene of creation, featuring the sea and mountains and trees and animals.

"The kids liked that idea that it was going to be U.S.-wide and it's exciting to think that you are the first to be doing this," she said.

The students were outdoor-oriented, she said, with a number of them living on ranches and many heading to the beaches on weekends. While the environment in their community was in fairly good condition, the coastal town was just a couple hours north of Santa Barbara, the site of a major oil spill in 1969. The blown Union Oil well dumped more than 4 million gallons of oil into the water, creating an 800-square-mile oil slick and killing thousands of seabirds and sea life. At the time, it was the largest oil spill in U.S. waters and has only been surpassed by the 1989 Exxon Valdez and 2010 Deepwater Horizon spills.

While the oil spill never extended as far north as San Luis Obispo, Taylor remembers the long-lasting impact on the beaches it contaminated. "For years afterwards, you could walk on the beach and get tar on your feet," she said.

The Santa Barbara spill was in the minds of the Mission students as they planned their own Earth Day events. They liked the idea of being a part of a new civic celebration, to be among the first. Their teacher shared their excitement. It's a feeling that has persisted with Taylor for 50 years.

"I'm just happy it's still going. That there still is an Earth Day."

A view of Earth as seen from the Apollo 13 spacecraft during its journey home on April 17, 1970 (Wikimedia Commons/NASA)

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff. His email is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]