A woman collects water for washing as floodwaters begin to recede in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai near Beira, Mozambique, in March. (CNS/Reuters/Mike Hutchings)

The impacts of climate change, both in the United States and across the world, are not affecting all groups equally, said academics and activists at an environmental justice symposium April 3 at the Catholic University of America.

The daylong conference, titled "Social Dimensions of the Climate Crisis," was sponsored by the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies and the National Catholic School of Social Service, both at Catholic University, and the Georgetown University Law Center Campus Ministry.

Speakers at the event emphasized how climate-related environmental disasters disproportionately affect low-income and minority communities around the world — a reality they said will worsen as global temperatures continue to rise in conjunction with increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

"Climate change is going to impact everybody, but folks who are already at risk are going to be differentially impacted," said Sacoby Wilson, a professor of applied environmental health at the University of Maryland.

Each of the presenters spoke for 30 minutes before participating in a question-and-answer portion. All spoke to the realities of climate change, provided data and examples of inequity and discussed viable ways to address the crisis.

Outlining the current crisis

"This is the main message we want to pass along: Climate change is not a distant threat. It is right here and right now, and we have to work right here and right now," said Astrid Caldas, a senior climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, a national nonprofit science advocacy organization.

Caldas outlined the scientific consensus that global temperatures have risen 1 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. That warming has contributed to effects like more powerful hurricanes, rising sea levels, severe forest fires, intense rainfall and a warming Arctic. To localize the impacts for the D.C. region, Wilson pointed to rising sea levels in Maryland and increased heat-related deaths in the nation's capital.

Caldas said that society, depending on its response, still has control over how bad things may get in the second half of the century. If worldwide carbon dioxide emissions decline by 40% to 60% of 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050, she said global temperature warming could be limited to 1.5 C — often considered a safer limit, particularly for low-lying islands and coastal communities — by the end of the century.

Limiting the rise to 1.5 C is important, Caldas said, as every half degree of global temperature rise creates consequences for millions of people around the world.

Contamination without representation

Speakers at the symposium stressed that general conversations about adaptation and preparedness for climate change do not go far enough.

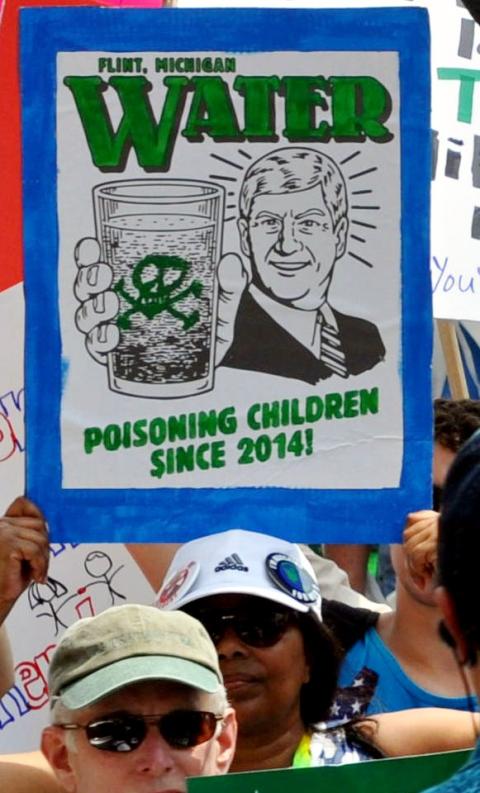

People's Climate March, Washington, D.C., April 29, 2017 (Flickr/Edward Kimmel)

"Climate change does not, in my opinion, cause environmental injustice. It reveals it," Wilson said.

"We must emphasize disproportionate impacts on communities of color and low-income communities," Caldas said. "This disparity of distribution of hazardous facilities and concentration of toxic pollutants near low-income and minority communities are mostly unnoticed by the unaffected population."

Wilson illustrated this disparity in the U.S. by citing multiple examples of environmental racism, or what he calls "environmental slavery" or "oppression":

- After Hurricane Harvey in 2017, toxic spills into poor neighborhoods surrounding the Houston Ship Channel, which serves the largest petrochemical complex in the U.S.;

- Lead exposure of children in Flint, Michigan;

- Power plants currently being built in the unincorporated town of Brandywine, Maryland;

- Poor farmers drinking contaminated water after Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018.

Each of those situations, he said, exemplify how planning and zoning make marginalized communities more vulnerable to environmental disasters.

"How can we protect future generations if we have kids living in toxic environments?" Wilson asked. "What are we doing to address and improve the infrastructure to make these communities more resilient?"

Socioeconomic factors make hazards and disasters worse for poor communities because they often already lack access to resources like health care, healthy foods and public transportation, Caldas said.

Wilson also urged the audience to think globally and be aware of who is impacted by the consumption of fossil fuels. "The global North is disproportionately impacting the global South," he said.

Advertisement

Joan Rosenhauer, executive director of Jesuit Refugee Service/USA, explained how climate change is causing displacement of people at a rate the world has never before experienced. She referred to climate change as a "threat multiplier."

"Climate change is now found to be the key factor accelerating all other drivers of forced displacement," she said.

In the case of the Syrian refugee crisis, she noted how a five-year drought preceded outbreak of war in 2011 in the Middle Eastern nation.

According to Rosenhauer, 41 people are displaced each minute somewhere in the world due to an extreme weather event. She said that the United Nations Refugee Agency estimated that nearly 250 million people worldwide will be displaced by climate change by 2050.

'Moral passion' needed

In his morning presentation, William Dinges, a professor of religion and culture at Catholic University, connected environmental justice to social justice. He said that what is lacking in the current climate movement is "moral passion" and "spiritual moral energy" akin to that of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Caldas added that "advocacy is not a dirty word" and emphasized the importance of discussing science with anyone you can, from family to policymakers.

The climate scientist also advocated that audience members do their share of emissions reduction. Caldas said that a 2012 analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that if every resident of the United States reduced their carbon footprint by 20 percent, it would be the equivalent of taking 200 coal-fired power plants offline and replacing them with clean energy sources.

Wilson cautioned against environmental groups "helicoptering" into poor communities to suggest solutions without first building relationships with those communities. A core principle of environmental justice, he said, is that communities "speak with their own voice," meaning marginalized communities need a spot at the table when discussing solutions to environmental issues and possible paths forward.

"We have to be aware of our carbon footprint," he said, and understand "what that means to our connected humanity."

[Jesse Remedios is an NCR Bertelsen intern. His email address is jremedios@ncronline.org.]

Editor's note: To keep up with Catholic environmental news, sign up here for the weekly Eco Catholic email newsletter.