Pilgrims of Catholic environmental movements are seen Oct. 4, 2018, at the start of the climate walk in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican. (CNS/Reuters/Tony Gentile)

The world today is filled with the reality and repercussions of a changing climate.

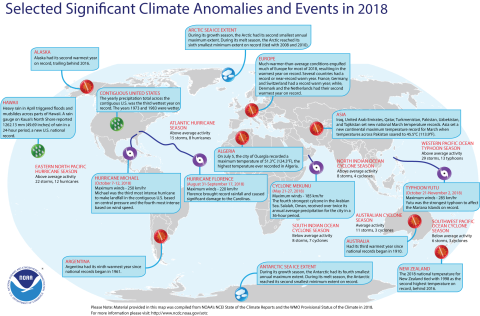

Glaciers are melting. Intense storms are strengthening. Seas are rising. Floods are spreading. Heat waves and droughts are prolonging. And the destruction and disruption all those events bring to people in all parts of the globe are increasing.

For decades, science has signaled this was the world to come as humans pump more and more heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, a consequential byproduct of industrializing nations on the back of fossil fuels. Yet despite the increasingly dire forecasts of even greater devastation ahead if current warming rates continue, scientists emphasize that time, albeit limited, remains to curtail such a future. But to do so would take a historic display of rapid action, economic transformation and international cooperation.

So far, science alone has not been able to provide the spark to overcome political inertia that has resisted such massive change. More and more, a prevailing belief is that a moral force is needed.

Into that space, Pope Francis introduced nearly four years ago his landmark encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," a compendium of Catholic teaching and thought on creation and humanity's role within it. With it, he outlined in unequivocal terms the essential duty to care for nature at the core of what it means to be Christian, and positioned the global Catholic Church as a prominent voice on climate change and environmental degradation that face populations across the planet.

In the time since, the world has continued to warm at a historic and dangerous pace.

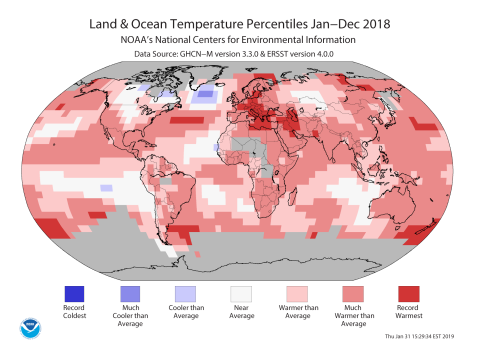

Each of the last four years together stand as the four hottest years on record. Pull back farther, the world's 20 warmest years recorded have all occurred in the past 22 years. In October, the United Nations climate science body issued a report that the planet, already 1 degrees Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) hotter than pre-industrial times, is on track to reach 1.5 C of warming by 2040, and as soon as a decade earlier. The rate of warming seen since the middle of the 20th century far eclipses what the planet has experienced in ages, or as NASA states, "unprecedented over decades to millennia."

Months after Laudato Si' was issued, world leaders adopted the Paris Agreement as the first global pact obligating all nations to work to stem warming below the 1.5 threshold. And while every country has now joined that climate accord — with the United States alone in expressing plans to exit — emissions rose in each of the last two years, and national climate plans only stand to limit the planet to 3 C warming by the end of the century.

Francis addressed his encyclical as an appeal to "the whole human family," requesting "a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet." He called not only for conversation but ultimately conversion and action to better care for a common earthly home that "is falling into serious disrepair." And in the case of climate change, address "an urgent need to develop policies so that, in the next few years, the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases can be drastically reduced."

The impact of the encyclical can be seen throughout the church. It has served for many as an awakening to Catholic teaching on creation care, and why the church cares about what gases enter the atmosphere. For others, it fortified and recharged ministries begun decades ago to address environmental degradation and serve those people most impacted.

Despite all that energy, there's still a feeling, with scientific forecasts firmly in mind, that the church has the potential to do more in how the world responds to climate change.

Perhaps a lot more.

"There's a lot of education that needs to happen still," said Dan Misleh, executive director of Catholic Climate Covenant, which has driven much of the encyclical's implementation in the United States. "Laudato Si' has been out there for going on four years, but there's still not enough Catholics or Catholic leaders who are paying attention to this."

Francis himself offered somewhat of a stock take in remarks at an early March interreligious Vatican conference in support of the United Nations' sustainable development goals, adopted three months after his encyclical's release.

"After three and a half years since the adoption of the sustainable development goals, we must be even more acutely aware of the importance of accelerating and adapting our actions in responding adequately to both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor — they are connected," he said.

An Indian farmer sits on a dry field in May 2018 outside Chhatarpur. The Catholic agency Caritas has launched a project that aims to end hunger across South Asia by 2030. Caritas India introduced the program in collaboration with its international partners to help farmers adapt methods to cope with erratic climate conditions. (CNS/EPA/Harish Tyagi)

Making creation care essential

Nine days after the encyclical reaches the four-year mark, Catholic Climate Covenant will gather approximately 250 leaders from various ministries to Middle America — Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska — with the goal "to try to jump-start" a deeper integration of creation care into what it means to be Catholic, Misleh told NCR. Or put another way: "Weaving a green thread through the tapestry of the Catholic Church."

"We're trying to help people in liturgy, education, facilities management, advocacy ... think through how they talk about environmental questions, and how we can share Catholic teaching on the environment more broadly through these ministries," the Catholic Climate Covenant director said.

The conference, June 27-29, will be the first of three such gatherings, with follow-ups in 2021 and 2023. San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy will deliver the opening keynote address, and Adrian Dominican Sr. Patricia Siemen is set to close the event.

In between speeches, ministry-specific breakout sessions will look at the challenges facing them and aim to develop resources and initiatives that can be taken home to then implement toward making creation care more essential to the Catholic faith.

That's not to say the encyclical hasn't planted any seeds.

The pope himself declared Sept. 1 a World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation, and invited Catholics to recognize the Season of Creation throughout that month. He proposed "care for our common home" as an addition to the traditional corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

More than 650 Catholic organizations worldwide have joined the Global Catholic Climate Movement, itself formed in anticipation of the encyclical.

The church in the Philippines has emerged a leader on environmental issues, motivated in no small part by devastatingly stronger storms fueled by higher, warmer seas. The Jesuit order made "caring for our common home" one of their four priorities for the next decade. An Indian archbishop urged Catholics to ditch plastic bags. A Laudato Si' Observatory was established in Costa Rica.

The bishops of coal-rich Poland issued a pastoral letter on the dangers of air pollution. U.N. diplomats and other policymakers continue to cite the encyclical. More than 120 Catholic organizations worldwide have publicly committed to divesting their finances from fossil fuels, including Caritas Internationalis and the bishops of Austria, Belgium and Ireland.

In the U.S., nearly 800 Catholic institutions — a mix of dioceses, religious orders, colleges, hospitals, parishes and nonprofits — have signed onto the Catholic Climate Declaration, pledging to pursue the Paris Agreement goals absent presidential leadership. The Catholic Climate Movement and U.S. bishops' domestic justice committee, among others, have lobbied for climate and environmental health policies.

Dioceses and parishes have installed solar panels and examined energy usage. The church in Vermont held a Year of Creation. Hundreds of parish creation care teams have formed, some existing long before the encyclical. Religious sisters and Catholic Workers have worked to block oil and gas pipelines.

Catholic academics created a free online textbook integrating environmental science, ethics and theology, and universities have held countless conferences. Catholics are getting offline and outdoors in Wisconsin.

Even as the U.S. church has made strides, the sense is that Catholic engagement on climate change, and environmental issues more broadly, has been more piecemeal than prevalent. That despite seeds planted, it has yet to take root and rise to the level of prominence that Francis saw his encyclical achieving, to "help us to acknowledge the appeal, immensity and urgency of the challenge we face."

"We are theologically still very narrow when it comes to reconceiving the human person within the wider realm of creation," said Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio, a theologian at Villanova University who has studied extensively the integration of religion and science.

While there have been many good books, papers and academic panels, she said she sees little theological change stemming from Laudato Si'', or other church documents on the environment, so far.

"I see no real movement. I see a lot of good people and there's a lot of goodwill, but we are heading towards a very, very different world, a world that will bear the consequences of global warming," she told NCR. "And that's just our current reality."

Part of the issue Delio sees is that the church has yet to fully embrace evolution theologically and, with it, how the human person is seen and understood in a world of dynamic change and complexity.

Addressing moral theologians at the Vatican in February, Francis encouraged them to delve deeper into environmental responsibility. Noting that he has rarely heard confessions about polluting or harming the Earth, he added: "We still aren't conscious of this sin."

Catholic Climate Covenant has worked to educate and familiarize priests with church teachings on creation — from 13th-century Sts. Francis of Assisi and Bonaventure to more recently in the papacies of John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis — so that they feel more comfortable and competent in preaching on the topic. The organization has also created homily helps to identify ecological themes throughout the liturgical year.

But Delio said the reliance on theological classics like Augustine and Aquinas has, in a way, marginalized more modern thinkers, like Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Passionist Fr. Thomas Berry. To Delio, that has prevented the church from theologically taking on evolution and understanding nature from the dynamics of changing complexity she says is necessary to arrive at the worldview Francis holds up in the encyclical.

"We can't keep relying on medieval philosophies and theologies to do theology in the 21st century," she said. "We need to really do what science does, and that is shift paradigms. And we haven't done that."

'A lack of urgency and a lack of prioritization'

Two studies this year seek a better sense of the U.S. church's embrace, or lack thereof, of Laudato Si'. One survey has begun asking parishes nationwide how they have responded to the encyclical. Later this summer, a second study will examine how bishops have talked about the encyclical or climate change.

"People are obviously working with the encyclical and they're trying to incorporate it into parish life. So that's good," said Dan DiLeo, a consultant to Catholic Climate Covenant and director of Creighton's Justice and Peace Studies Program, who is leading the studies. "What has come through again and again [in the early parish survey results] is a lack of urgency and a lack of prioritization."

"It's kind of ancillary, and optional at best," he added.

In its initial 24 hours, the parish survey received roughly 800 responses. Of those reporting little environmental activity at their parish, parishioners said their priest doesn't prioritize the issue. Priests, in turn, said their bishops didn't emphasize ecological concern or, to bring things full circle, that their parishioners hadn't registered creation care as important to them.

An early takeaway from the initial round of data, DiLeo said, is "that it emphasizes the need for the entire church to be prophetic on the issue. That it's all the above — it's priests, it's bishops, it's laity."

A boy holds up artwork of the sun as children perform at the start of an international conference marking the third anniversary of Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" at the Vatican July 5, 2018. (CNS/Paul Haring)

At their November 2018 meeting, the U.S. bishops were expected to discuss, and perhaps vote on, joining the Catholic Climate Declaration.

But neither happened.

The re-emergence of the church's sexual abuse scandal upended most of the agenda. Still, had the bishops voted to sign their names, which was not a certainty, it would have come five months after the majority of Catholic institutions had signed on, and two months after those signatures were officially joined to a wider We Are Still In coalition pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions no matter the effort coming from the White House.

The situation served as an illustration that, more often, it has been the church outside the hierarchy — women religious, schools and development agencies, among others — leading the way on issues concerning the environment.

"Women religious have been out front on this for decades," DiLeo said.

Of the Catholic groups that have divested from fossil fuels, almost one-fifth have been congregations or orders of women religious. More than 150 of the signers to the Catholic Climate Declaration were communities of Catholic sisters.

Last June, the International Union of Superiors General launched an initiative aimed specifically at putting Laudato Si' into practice even further. Titled "Sowing Hope for the Planet," the two-year campaign "offers a practical and spiritual platform for solutions that are so desperately needed right now," said Sr. Sheila Kinsey, executive co-secretary of the organization's Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation Commission.

"Through this campaign we have the opportunity to organize the voice of the Sisters in the effort on many levels of structures in order to enhance and recognize our contribution to the care of our Common Home," she told NCR in an email.

In March, another survey began tracking how many congregations participated in the initiative and how they did so. Results will be shared at the International Union of Superiors General plenary in Rome in May. Early responses found sisters developing resources for parents, teachers and catechists; incorporating the encyclical into liturgies; offsetting carbon footprints by supporting development projects in Africa; and undertaking a variety of planting projects to promote biodiversity and reduce emissions.

Kinsey said the May plenary is expected to also produce a statement to determine the campaign's future direction.

Along with Catholic sisters, the church's development organizations have been working with communities across the globe in dealing with and adapting to the present-day effects of climate change.

In the Philippines, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean, that has typically meant responding to the aftermath of devastating storms. In Central America and Africa, often they have addressed the impacts of deforestation and drought, combating the former to better withstand the latter through restoring the soil and watersheds.

"We're really feeling it on the frontlines with those communities who are facing the disasters," said Lori Pearson, senior policy adviser on food security, agriculture and climate change for Catholic Relief Services, the U.S. bishops' international development agency.

She told NCR that Laudato Si' has been particularly inspirational to CRS and other development organizations within Caritas Internationalis. "It's such an articulation of what we are seeing on the ground, and then [Francis] brought it to this higher level and it's becoming a call to the church."

In October, the Catholic Church will give perhaps the greatest attention to environmental concern since Laudato Si' with the special synod on the Amazon — a critical ecosystem for the planet where issues of land use, indigenous rights, water access and sustainability all intertwine.

The Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network, or REPAM, has led much of the pre-synod preparations, while groups like Global Catholic Climate Movement have ramped up their focus on the South American rainforest. Pearson said that a Laudato Si' working group within Caritas has also increased its attention on the Amazon ahead of the synod.

"I think this will be very significant," she said.

The political barrier

Any conversation about the Catholic Church and the environment is bound to turn to the massive potential the church has to be a major force for good on the issue. They cite the size of the church and its global reach, the thousands of buildings and properties it owns (more than 70,000 in the U.S. alone) and the influence is possesses, even amid present scandals.

So, how to turn that potential into higher levels of action?

"That's the million-dollar question," said DiLeo, the Creighton theologian.

Appreciating the gravity of what the science is saying is a first step, he said. A second is greater recognition and understanding of the idea of integral ecology — an entire chapter in Laudato Si' — that climate change and ecological issues touch on every sector of public life and every ethical issue concerning the church.

Delio, the Villanova theologian, said that while the encyclical has raised the bar of consciousness on creation theology, what's needed is a coherent theology "that can filter out of the academy into the pew" that can process the big ideas Laudato Si' raises into what it means in people's daily lives.

"If we want a real change, a green Earth, we need to get practical. We need practical theology. Theology that translates into people's lives, and we need principles and language to help do that," she said.

Delio suggested the Gospels as a starting point, taking values expressed there — community, attentiveness, compassion and that God's love extends to all creation — and then examining them through the lens of evolution.

"The type of change that's needed cannot be cosmetic. It's not an intellectual change. It's not a cosmetic change. It's a deep ontological change in the sense, in the way we understand what we are as human persons, what we are within this wider realm of creation and how God may be acting in this dynamic flow of created life," Delio said.

The parish surveys DiLeo has reviewed so far confirm a readily apparent barrier to the church in America raising the moral and ethical rationale for addressing a warming planet:

Politics.

That reality raises the question, DiLeo said, "about whether church leaders are willing to be prophetic in the face of what you might call anticipated resistance."

Francis regularly acknowledged his intention for the encyclical to influence negotiations at the United Nations climate summit in Paris that year. Since then, the political scene has changed dramatically.

President Donald Trump has stated he will withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement at the earliest date — Nov. 4, 2020, a day after the next presidential election — which would place the greatest contributor to historical carbon emissions out of step with the rest of the world. The rise in nationalist sentiments has led other countries, like Brazil, to question their commitments to reducing emissions while doubling down on drilling, mining and logging.

Students hold signs in New York City March 15 to demand action on climate change. Students from around the world participated in the "strike." (CNS/Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

The Vatican delegation at COP24, the 2018 U.N. climate summit, concluded the global leaders there "struggled to find the will to set aside their short-term economic and political interests and work for the common good."

While commending the completion of a rulebook to implement the Paris Agreement, the Vatican said it "does not adequately reflect the urgency necessary to tackle climate change, which 'represents one of the principal challenges facing humanity in our day' " — quoting Laudato Si'.

At the same time, the climate issue has amplified in America in 2019, in no small part to the ongoing debate around the Green New Deal. The nonbinding congressional resolution stakes out ambitious goals to make the United States carbon-neutral by 2030 and transform its energy grid away from fossil fuels, while also addressing "systemic injustices" in labor, wages, race, housing and health.

While conservatives and even some Democrats have dismissed the Green New Deal as unrealistic or too radical, it nonetheless represents the most substantial conversation on climate change in Congress since the failed cap-and-trade bill nine years ago.

House Democrats have held more than a dozen hearings on climate change so far. And early indications are that climate change could be a prominent issue in the Democratic presidential primaries. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and other Catholic groups lent support to a climate-fee-and-dividend bill in the House, though they have refrained from any public position on the Green New Deal.

Advertisement

Among the Green New Deal's proposals is a call for "a just transition for all communities and workers" as the country moves toward net-zero emissions. Since 2010, more than half of the 530 U.S. coal-fired power plants — and 95 within the last four years — have announced plans to close. While representing progress of a world less reliant on fossil fuels, it raises uncertainty for the communities and workers whose lives, finances and culture developed around extractive industries.

The topic of a just transition initiated last summer the beginning of a series of meetings between Franciscan Action Network, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, Creation Justice Ministries, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and the Edison Electric Institute, an association representing many of the nation's power companies.

"We actually talked about Laudato Si' in one of our meetings," said Patrick Carolan, Franciscan Action Network executive director, who also passed out copies of the encyclical.

To him, the meetings reflect the dialogue Francis requested through the papal document.

"We have to build these relationships. These are people who provide the electricity; we have to be in the room having discussions with them, to try to help shape policy with them. ... If we don't start doing all of that, then we're going to keep spinning our wheels," he said.

In the encyclical, the pope asked the people of the planet to not just consider questions of what type of world they want children to grow up in, what they want to leave behind for future generations, but to "struggle with these deeper issues" and others about what is the purpose of our life in this world.

At stake in those deliberations, Francis wrote in Laudato Si' Paragraph 160, "is our own dignity."

"Leaving an inhabitable planet to future generations is, first and foremost, up to us. The issue is one which dramatically affects us, for it has to do with the ultimate meaning of our earthly sojourn.

"Doomsday predictions can no longer be met with irony or disdain. We may well be leaving to coming generations debris, desolation and filth."

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]

Editor's note: To keep up with Catholic environmental news, sign up here for the weekly Eco Catholic email newsletter.