At yesterday’s conference on tuition tax credits, John Carr, who leads the Justice, Peace and Human Development office at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops said he felt a bit like an “outsider.” Marie Powell, who heads the USCCB’s Education Office recalled going to a social justice gathering and having a similar feeling. In part, no doubt, this “outsider” sensation comes simply from the division of labor at the USCCB: Different parts of the organization handle different issues. People like to bemoan bureaucracy, but in a complex society, there is no alternative. Expertise matters and no one can be expected to be an expert in everything.

But, there is a deeper reason for the divide and it surfaced in some of the question-and-answer sessions after the panels. For many years, those who support finding ways to provide tuition tax credits, or vouchers, or some other means to lighten the financial burden on parents who send their children to Catholic schools, joined forces with more libertarian organizations that also supported school choice. One of the arguments, often heard in discussions of vouchers or tuition tax credits, is that only a healthy competition between public and private schools will produce the kind of market forces that will improve both private and public schools. Indeed, some in the room yesterday rehearsed that argument and said it was essential to employ if there was any hope of enlisting middle class support for tuition tax credits.

This argument is wrong at several levels. First, while the market is undoubtedly the best means yet devised for distributing goods and services as well as creating wealth, children are not goods (nor services). And, obviously, children were not created by the market but by God. The market can do many things well but it cannot do all things. Second, trying to apply market considerations to schools misunderstands the nature of our obligation to children. Markets produce winners and losers, but no devotion to market principles justifies permitting some children to “lose” in order to make an ideological point. Third, while our friends at the CATO Institute may not have noticed, the increasingly unregulated market of the past thirty years has not been very kind to the middle class. I doubt that using a “market-based” argument will appeal much to those whose wages have been stagnant or falling while the market has heaped billions of dollars on financial managers who have never produced anything of value nor invented anything that improves the human condition but got rich by showing up when money changes hands and taking a cut.

Carr, and others, made a different argument for tuition tax credits, an argument which, unsurprisingly, was more coherent with Catholic ethics. There is a social justice component to the tuition tax credit debate. Some of our schools are failing. Why not rescue as many as we can from failing schools while we all try to figure out how to improve those schools? Indeed, in an America where social mobility is declining, where if you are born poor you are increasingly likely to die poor, our Catholic schools open a door to a better future, especially for inner city poor children and for immigrants. The special role of Catholic schools in helping immigrants is part of our history as well as our present and future.

One of the questioners, I believe it was a gentleman from CATO, actually said that it would be better not to invoke such social justice language. He said it turned off middle class voters. It may or may not turn off middle class voters, but we don’t take polls in the Catholic Church to decide what we must and must not believe. Our responsiveness to the moral demand for justice is intrinsic, rooted in our beliefs about who Jesus is and what He commanded us to do. Whether it is a good talking point or not, we cannot stop talking about social justice without sacrificing our Catholic identity.

Our political landscape is a confused one. One of the panelists talked about recent successes the tuition tax credit movement has had in certain states. He noted that the movement is supported by Gov. Scott Walker in Wisconsin and Gov. John Kasich in Ohio. I confess, this makes me nervous. It is not just that these men are polarizing figures and hitching the cause of Catholic schools to their wagons is dangerous. It is that these men have been the most prominent politicians in the country in the GOP’s assault on unions. I understand that the teachers’ unions are one of the primary obstacles to getting better funding for our Catholic schools, and shame on them. But, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with men who are attacking the Church’s social justice teachings on unions because they support the Church’s social justice teachings on the rights of parents to educate their children has more than a whiff of cafeteria Catholicism. It should make us very uncomfortable. In politics, we should feel uncomfortable. I feel that way all the time when I am with someone who champions the cause of immigrants but is deaf to any concern for the unborn. But, let’s be honest about it: There is a cafeteria Catholicism on the right as well as the left.

The discussion reflected a deep divide within conservative political circles, and one that goes way back in time. In the September, 1981 issue of the journal Reason, Professor Murray Rothbard, a libertarian champion, praised the Rev. Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority for launching an “uprising” against the public schools. Rothbard denounced the “secular humanist values” taught in the public schools but he also denounced any attempt to return to the pre-Dewey days for which Falwell seemed to yearn: “One is trying to force a majority to accept hedonism and secular humanism; the other is trying to compel a majority to swallow the Protestant ethic.” Rothbard announced he favored the complete privatization of education because only then “will we be free of any group of tyrants who might wish to force their values, whatever they may be, down the throats of the rest of us.” That language about “forcing their values” is how libertarians speak. It is not how Christians speak.

Last month, in the print edition of NCR, I published a profile of Ovide LaMontagne, a leading Catholic conservative in New Hampshire. He, also, liked to talk about the importance of choice when it came to private schools and private markets, but not so much when it came to private parts. Conversely, I could not be more tired of liberals who champion choice when it involves human sexuality but seem completely unalert to the value of choices when it comes to, say, conscience protections from government mandates. The Church of course is never and can never be in favor of “choice” per se. We honor human freedom and free will – indeed, listen in to some NPR shows with scientists and you will encounter those who believe free will is a sham, that we humans are nothing more than a congeries of biological impulses in the brain, and I will predict that sooner rather than later the Church will be the principal defender of free will in our culture. But, we Catholics are for good choices, not bad ones, and we recognize that you can’t divorce the freedom we enjoy from the moral dictates that permit that freedom to be directed towards the truth. We may make common cause on this issue or that with our libertarian friends, but they do not share our worldview. On the left, the divergence arises in terms of life issues and gay marriage. On the right, the divergence arises in terms of market idolatry and hostility to organized labor. I have never been in favor of the idea of a “Catholic Party” but I am foursquare in favor of the need for the Church to stand against the libertarian tendencies that afflict both the left and the right of American politics.

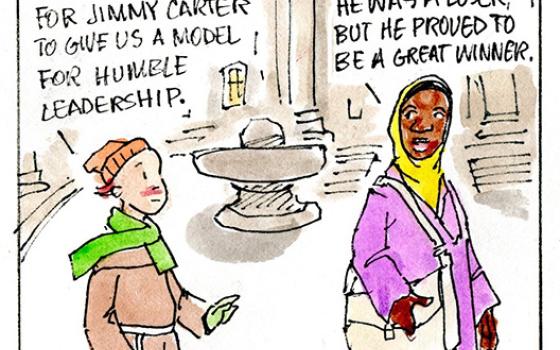

What was clear from Carr’s and Powell’s presentations yesterday is that, whatever the political landscape, the staff at the USCCB is fully on board what is clearly one of the central themes of Pope Benedict’s pontificate, the need to root all of our various political, economic and social attitudes in our core, common doctrinal beliefs. We Catholics must understand that life and human dignity issues are also social justice issues, and that social justice issues are, in turn, also life and dignity issues, and that our concern for our Catholic schools is related both to our belief about the primacy of the family in society and our concern for justice for the poor and underprivileged. It all hangs together because it is all rooted in a theological anthropology, a belief in the human person as a child of God first and foremost, and that theological anthropology is, in turn, rooted in the self-revelation of Jesus Christ. The Church must be engaged in the political world, and sometimes we will be linked with people who do not share our views on all issues, to be sure. But, what we can never stop doing is proclaiming what we believe about the human person and about Jesus Christ. As the fathers at Vatican II wrote in the much-cited 22nd paragraph of Gaudium et Spes, “The truth is that only in the mystery of the incarnate Word does the mystery of man take on light. For Adam, the first man, was a figure of Him Who was to come, namely Christ the Lord. Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and His love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear.”