Pope Benedict XVI is midway through his trip to the United Kingdom, and so far reaction has been all over the map, from wild enthusiasm among devotees, to overt hostility among determined protestors, to benign indifference in a broad swath of secular society. Of course, the pope always evokes a range of opinions, but they’re rarely on full public view as they are here.

Predictions of disaster in the run-up to the trip have largely failed to materialize, in part because Benedict XVI is simply a more gracious and kindly figure than his stern public image suggests, in part because Benedict has once again dialed up his “Affirmative Orthodoxy,” striking a deliberately positive tone. Within minutes of his arrival, he had told Queen Elizabeth II that Britain should be proud of its Christian and humanitarian traditions and praised the Northern Ireland peace agreement, and this German pope even thanked the British for standing up to the Nazis.

Yet dissent still dogs the visit, which was clear this evening outside Westminster Abbey. A large throng of pilgrims lustily sang hymns in an attempt to drown out an assortment of protestors, including advocates for victims of priestly sexual abuse, radical Evangelicals who regard the pope as the anti-Christ, and secularists who have a truckload of objections to the pope’s position on issues such as abortion and gay marriage. Tomorrow, a major anti-papal march is scheduled in downtown London.

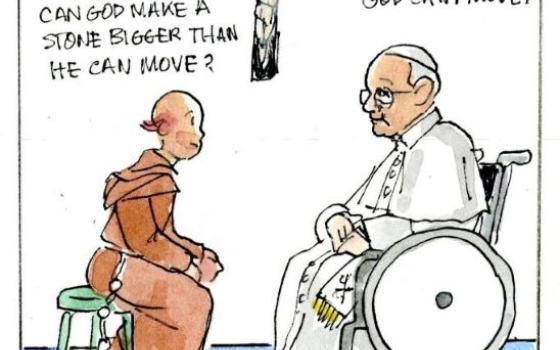

(For the record, some protestors along the way have shown a lively sense of humor. My personal favorite was the guy in Scotland holding a sign that read, “Down with this sort of thing!” Second place goes to the three members of a gay rights group that stood outside a papal meeting with Catholic schools this morning, clad only in tight shorts and golden wings.)

If Benedict doesn’t seem to be winning over his most determined critics, there is some evidence that the PR tide may be turning in his favor. Today, Labor MP Kate Hoey, a liberal who disagrees with the Catholic church on a wide variety of issues, announced that she was fed up with “carping about the trip from atheists with an axe to grind and a book to plug,” and would therefore join a welcoming party for the pope when he visits a center run by the Little Sisters of the Poor in her south London district.

Beyond giving a shot in the arm to the Catholic minority in the U.K., Benedict is trying to reach out this week to three constituencies: all those inside and outside the church scandalized by the sexual abuse crisis; secular society, whose attitudes towards religion range from benign indifference to outright hostility; and the Anglican Communion, whose members often look upon popes generally, and this pope in particular, with deep skepticism.

In a sound-bite, Benedict’s message to each group could be summed up as follows: We get it; we’ve got it; let’s share it.

We Get It

Though the Catholic church in the U.K. has been largely spared the massive sex abuse scandals that have rocked the United States, Ireland, Germany, now Belgium, and other nations, the British press has been relentless in covering the story, and public attitudes show it. A poll commissioned by CNN on the eve of Benedict's trip show that 77 percent of British adults, and 56 percent of British Catholics, believe the pope has not done enough to punish priests guilty of sexual abuse. Only 4 percent of the general British public said he has done enough; the rest said they didn't know.

One expression of that climate of opinion came from a Welshman named Bryan Junor, who came down to London today to hold a banner reading "Abstinence makes the church grow fondlers."

As he has during several past papal trips, Benedict didn't wait to touch down in the U.K. to tackle the sexual abuse crisis. Instead, he chose to take a question on the subject during a brief session with reporters aboard the papal plane.

The pope confessed to "sadness that the authorities of the Church were not sufficiently vigilant and not sufficiently quick and decisive in taking the necessary measures" to combat the crisis. He called the church's commitment to victims its "first priority," promising "material, psychological and spiritual help." He also said that priests who have abused must never again be allowed access to young people, because they suffer from an ilness that cannot be cured with "willpower."

Benedict also expressed personal incomprehension that a priest, who has promised to devote "his entire existence so that the Good Shepherd who loves, helps and guides us to the truth will be present in the world," could then fall into what the pope described as "this perversion of the priestly ministry."

In a more spiritual key, the pope described the sexual abuse crisis as an invitation "to experience precisely a time of penance, a time of humility, and to renew, to learn again, absolute sincerity."

The pope obviously wanted to say all that at the outset, because the Vatican collects questions from reporters in advance and thus allows Benedict a chance to craft his replies.

In a speech to Catholic educators today, Benedict also made a more oblique reference to the crisis, talking about the importance of creating "a safe environment for children and young people."

"Our responsibility toward those entrusted to us for their Christian formation demands nothing less," the pope said.

In terms of persuading the pope's critics, it's not clear his comments will cut much ice. When Benedict came to the United States in April 2008, he hadn't really yet engaged the crisis in a public way, so his candor on that occasion – speaking about it on five occasions, and meeting with victims for the first time – won wide praise, and was largely responsible for making the trip a public relations triumph. A Gallup poll afterwards showed that Benedict got a ten-point bump in his favorability ratings in America, and 60 percent of Americans said the trip had given them a more positive impression of the church.

Now, however, papal expressions of contrition and determination have become more routine, so they don't have the same impact. Critics say we've heard it all before, and what we want is action: for example, accountability for bishops who have mismanaged the crisis, transparent cooperation with police and civil authorities, and a uniform global "zero tolerance" policy.

The Survivor's Network of Those Abused by Priests, the main victims' advocacy group in the States, issued a statement calling Benedict's words "disingenuous." The problem wasn't that the church failed to be fast, SNAP asserted; it moved very fast, they charged, in the wrong direction, covering up the problem rather than facing it.

Yet Benedict's comments at least provided a reasonably positive news day for the pope vis-à-vis the crisis – especially compared to the alternative, which was saying nothing and creating impressions that he was ducking the issue. Benedict's words on the plane also provided talking points to innumerable local Catholic commentators when faced with questions about the crisis.

Whatever one thinks of the pope's policy response, his comments may at least suggest to some skeptical onlookers that he "gets it" in terms of the magnitude of what's happened.

We've Got It

Perhaps the most keenly anticipated speech of Benedict's four-day trip came this afternoon in Westminster Hall, where the pope spoke to political, social and business leaders about the role of faith in politics. The setting was evocative; Westminster Hall is where St. Thomas More, the great English scholar and statesman, was tried and condemned in 1535 for refusing to acknowledge the King as also the head of the church.

Among the other VIPs in attendance were four former British Prime Ministers: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

In principle, this could have been an explosive address, given the clear differences between the Catholic church and the U.K. on any number of hot-button social issues, from gay marriage to abortion to embryonic stem cell research. Instead, Benedict delivered an "Affirmative Orthodoxy" tour de force. He lauded Britain's legal and political tradition, with its emphasis on individual rights and the separation of powers, as "an inspiration to many across the globe," and said that it shares much common ground with Catholic social teaching.

The heart of the speech was a pitch for constructive dialogue between faith and reason, and therefore between church and state. Reason shorn of faith, he warned, becomes destructive ideology; faith without reason, shades off into a distorted "sectarianism and fundamentalism."

Praising Britain's democratic tradition, he argued that democracy needs an ethical foundation in order to function successfully.

"If the moral principles underpinning the democratic process are themselves determined by nothing more solid than social consensus, then the fragility of the process becomes all too evident," he said.

That, the pope argued, is where religion enters the picture, as a source of values that provide an orientation for public life. He pointed to Britain's role in abolishing the slave trade, a crusade he said was inspired by "ethical principles, rooted in the natural law."

Benedict laid out a laundry list of issues where church and state can work together: curbing the arms trade, spreading democracy, debt relief, fair trade and development, environmental protection, clean water, job creation, education, support to families, immigration, and healthcare.

Defense of the world's poor was a special emphasis, and Benedict used sharp language to drive home the point.

"The world has witnessed the vast resources that governments can draw upon to rescue financial institutions deemed 'too big to fail,'" the pope said. "Surely the integral human development of the world's peoples is no less important."

"Here is an enterprise," he said, "worthy of the world's attention, that is truly 'too big to fail.'"

In order for that cooperation to succeed, the pope argued, political leaders need to see religion not "as a problem for legislators to solve, but a vital contributor to the national conversation." In that context, he warned against "the increasing marginalization of religion, particularly of Christianity," insisting that public expressions of faith such as Christmas festivals should not be discouraged and that Christians in public roles should not be compelled to act against their conscience.

In a phrase, the pope's case for religious faith in a pluralistic culture boiled down to "we've got it" – with the "it" referring to the spiritual and moral instincts which a democratic society needs in order to thrive.

It's hard to know what the long-term effect of that argument may be, but for an afternoon, Benedict at least made Catholicism look rational, constructive, and committed to partnership in pursuit of the common good. In the secular milieu of contemporary Britain, where the historical tradition of anti-Catholicism has drawn new life from the sex abuse mess, that alone is no mean feat.

Let's Share It

So many obituaries have been written of Anglican/Catholic relations in recent years that people could be forgiven for thinking it's already dead. God knows headaches abound, from long-standing differences over women's ordination and homosexuality, to the more recent contretemps created by Benedict's decision to create new structures, called "ordinariates," to welcome Anglicans who decide to jump ship.

Benedict, however, put a largely positive spin on things in his meeting this afternoon with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, at Lambeth Palace. Benedict and Williams are both accomplished theologians, both somewhat shy and cerebral, and thus share a strong personal rapport.

At the outset, Benedict said he did not come to dwell on "the difficulties that the ecumenical path has encountered and continues to encounter," but rather on "the deep friendship that has grown between us" and the "remarkable progress" in Anglican/Catholic ties in the last forty years.

Benedict has long stressed that different Christian churches and different religions, despite theological disagreements, share core values that can foster partnerships in social, cultural and political affairs. That's the "let's share it" component of the pope's pitch.

He returned to the theme today, calling on Anglicans and Catholics to promote "peace and harmony in a world that so often seems at risk of fragmentation."

The pope didn't entirely pull his punches, insisting that Christians "must never hesitate" to proclaim the uniqueness of the salvation won by Christ, and that while the church is called to be inclusive, that must never come "at the expense of Christian truth." Some Anglicans no doubt heard a gentle rebuke in those words, especially because inclusion has long been the mantra of progressive Anglicans in favor of women priests and bishops and blessing gay marriages.

Yet Benedict's tone remained largely upbeat, offering Cardinal John Henry Newman, an Anglican convert to Catholicism whom the pope will beatify on Sunday, as a model of handling differences "in a truly eirenical spirit" and a "deep longing for unity in faith."

While no new breakthrough in Anglican/Catholic ties seems imminent, today's events at least confirmed that the dialogue will go on.

John Allen will be filing reports throughout the Papal visit to the U.K. Sept. 16-19. Stay tuned to NCR Today for updates.