Analysis

A thoughtful recent piece in The Economist asserted that Catholicism’s response to the sexual abuse crisis in Europe has been clumsy in countries where the church is accustomed to unchallenged power, while it’s been “much more intelligent, and appropriately humble ... in places where the church was used to fighting in a noisy democratic space.”

If noisy democratic spaces are good for the faith, then Pope Benedict XVI’s Sept. 16-19 visit to England and Scotland ought to be just what the doctor ordered. All indications are that the pontiff is stepping into a buzz saw.

Most spectacularly, a small but vocal contingent wants Benedict served with an arrest warrant for his role in the sexual abuse crisis, just like Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, accused of human rights abuses, was detained in London a decade ago, triggering a 16-month legal battle. It’s not going to happen -- Benedict is on a state visit, and neither the queen nor the prime minister want their guest tossed into jail -- but the persistence of the idea is revealing.

In the media, the BBC is airing another documentary on the sex abuse scandals, called “Trials of a Pope,” while human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robinson is publishing a book arguing that Benedict should be stripped of his status as “the one man left in the world who is above the law.” In the streets, a mix of secularists, gay rights activists and others plan to protest in London on Sept. 18. And there’s grumbling about the trip’s estimated $18.5 million price tag.

How well Benedict succeeds in cutting through that noise could affect not only Catholic fortunes in the United Kingdom, but the pope’s broader ambition for a “new evangelization” across the secular West.

Benedict will arrive in Edinburgh, Scotland, on Thursday, Sept. 16, for a meeting with the queen at Holyrood Palace before celebrating an open-air Mass in Glasgow. In London the next day, Benedict will meet the archbishop of Canterbury in Lambeth Palace, and will address members of British society in Westminster Hall.

On Saturday the pope will celebrate Mass in Westminster Cathedral and lead a prayer vigil in Hyde Park, while on Sunday, Sept. 19, Benedict will travel to Birmingham to beatify Cardinal John Henry Newman.

Along the way, three distinct audiences await:

- English society, broadly secular and historically ambivalent about the papacy;

- Other believers, especially the Anglicans;

- Local Catholics (4.2 million in England and Wales and 700,000 in Scotland).

Secularism is famously Benedict’s bête noire, and he’s coming to the right place to engage it. A recent national study found that in a household in Great Britain today where both parents are actively religious, a child stands only a 47 percent chance of becoming religious. In a household where just one parent is religious, those odds drop by a factor of half, to 24 percent, and where neither parent is religious, the odds that a child will become religious plummets to a statistically insignificant 3 percent.

David Voas of the University of Manchester draws the obvious conclusion: “In Britain, institutional religion now has a half-life of one generation.”

Benedict’s core challenge is to persuade a jaded secular public to take a new, more appreciative look at the social role of religious faith. There’s precedent to suggest he’s capable of pulling it off: In France in September 2008, his speech at Paris’ Collège des Bernardins, on the monastic contribution to Western culture, was hailed as a masterful reflection on church/state relations even by the most ideologically charged defenders of French laïcité.

Benedict’s core challenge is to persuade a jaded secular public to take a new, more appreciative look at the social role of religious faith. There’s precedent to suggest he’s capable of pulling it off: In France in September 2008, his speech at Paris’ Collège des Bernardins, on the monastic contribution to Western culture, was hailed as a masterful reflection on church/state relations even by the most ideologically charged defenders of French laïcité.

Ecumenically, Benedict hopes to persuade dubious Anglicans that his decision last year to authorize new structures to welcome ex-Anglicans was not an act of poaching intended to further destabilize the Anglican Communion. Instead, he’ll pitch it as a gesture of respect for the Anglican heritage, intended to point toward a future of what ecumenical experts call “reconciled diversity.”

Officially, Archbishop Rowan Williams of Canterbury, a theological admirer of Benedict, is likely to issue soothing assurances, but reaction at the Anglican grass roots is harder to predict.

Within the Catholic fold, Benedict also faces pushback. Advocates of women priests have put ads on London buses reading “Pope Benedict -- Ordain Women Now!” A group called Catholic Voices for Reform has publicly presented Benedict with questions on matters such as “corruption” and “mindless obedience.”

The pope is unlikely to engage such protest directly, focusing instead on his long-term project of promoting Catholicism in the secular West as a “creative minority” -- a term he borrows from British historian Arnold Toynbee.

The pope sees that as a two-stage effort:

- Fostering a strong sense of Catholic identity by emphasizing traditional markers of Catholic thought, speech and practice;

- Applying that identity to broader social debates, rather than retreating into a ghetto.

That first point especially may be a tough sell for some English Catholics, who, as Peter Sanford observed in a recent Guardian piece, have long been concerned with social acceptability. On that level, Sanford opined, Benedict may want “to stiffen the collective Catholic resolve.”

Despite everything, there’s clearly a case for hope about Benedict’s foray onto “this scepter’d isle.”

For one thing, papal trips into tense environments almost always go better than worst-case scenarios suggest. Most of those put off by the pope will choose the couch or the pub, not the barricades, as the right venue to register their dissent.

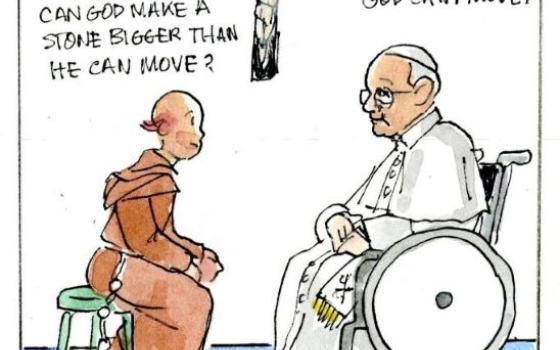

Moreover, any contact with Benedict at all usually improves his image, since the real man is inevitably less foreboding than the caricatures suggest.

Back in the day, Italian Cardinal Roberto Tucci, organizer of papal travel under John Paul II, used to say that people liked the singer but not the song. Benedict almost has the opposite problem -- many aspects of his message go over fairly well, although he personally is plagued by chronic image problems.

A recent poll in the U.K. took 12 statements from Benedict’s social encyclical Caritas in Veritate -- such as “investment always has moral as well as economic significance,” and “an overemphasis on rights leads to a disregard for duties” -- and found that significant majorities agreed. A robust 63 percent even concurred that it’s “irresponsible to view sexuality merely as a source of pleasure.” As BBC broadcaster Ed Stourton put it, “People are looking for an alternative to the moral relativism that has become the ideology of today,” so the pope has a natural appeal to the “disillusioned.”

This will be the first time many Scots and Brits have actually seen Benedict, and if his typically gentle demeanor persuades some to open their ears, these results suggest they may like what they hear -- or at least be willing to ponder it with respect.

[John L. Allen Jr. is NCR senior correspondent. He will be in the United Kingdom covering Pope Benedict XVI’s Sept. 16-19 trip.]

John Allen will be filing reports throughout the Papal visit to the U.K. Sept. 16-19. Stay tuned to NCR Today for updates.