Portraits of six African Americans who are sainthood candidates are displayed in the lobby of the Catholic Center in Baltimore in November 2023 for Black Catholic History Month. The six are: (from left top row) Pierre Toussaint; Mother Mary Lange; and Fr. Augustus Tolton; from left bottom row are Mother Henriette Delille; Sr. Thea Bowman; and Julia Greeley. (OSV News/Catholic Review/Kevin J. Parks)

There is not a single African American Catholic canonized as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church.

This omission persists even as Black Catholics have remained faithful despite the church's complicity in slavery, segregation, discrimination and racial injustice. This complicity is not that of an unengaged bystander, but rather, as an active participant. Several examples are found in Shannen Dee Williams' book, Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle as she exposes the racism embedded in white religious orders, bishops and other quarters in the Catholic Church.

These failures are not all past; many continue to this day. Robert P. Jones' White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity includes data regarding the racial perspectives of white Christians. According to the data, 63% of white Catholics believe police killings of Black men are isolated incidents instead of a pattern of racial injustice. But only 38% of religiously unaffiliated whites agree. Also, 57% of white Catholics say that structural racial injustice does not impact Black economic mobility, versus only 40% of whites with no religious affiliation.

There are about three million Black Catholics in the United States today, with origins back to their 1565 arrival in St. Augustine, Florida. Black Catholic history and presence has been chronicled in many places, including Cyprian Davis' The History of Black Catholics in the United States and The Fire This Time by Kim Harris, M. Roger Holland II and Kate Williams.

Advertisement

One step toward healing could be canonization of the six African Americans currently up for consideration as saints. The "Saintly Six," as they are known in Black Catholic circles, are Venerable Pierre Toussaint, Venerable Henriette Delille, Venerable Fr. Augustus Tolton, Servant of God Mother Mary Lange, Servant of God Julia Greeley and Servant of God Sr. Thea Bowman. For several years now the Vatican has researched the records to determine if these individuals meet the qualifications for sainthood.

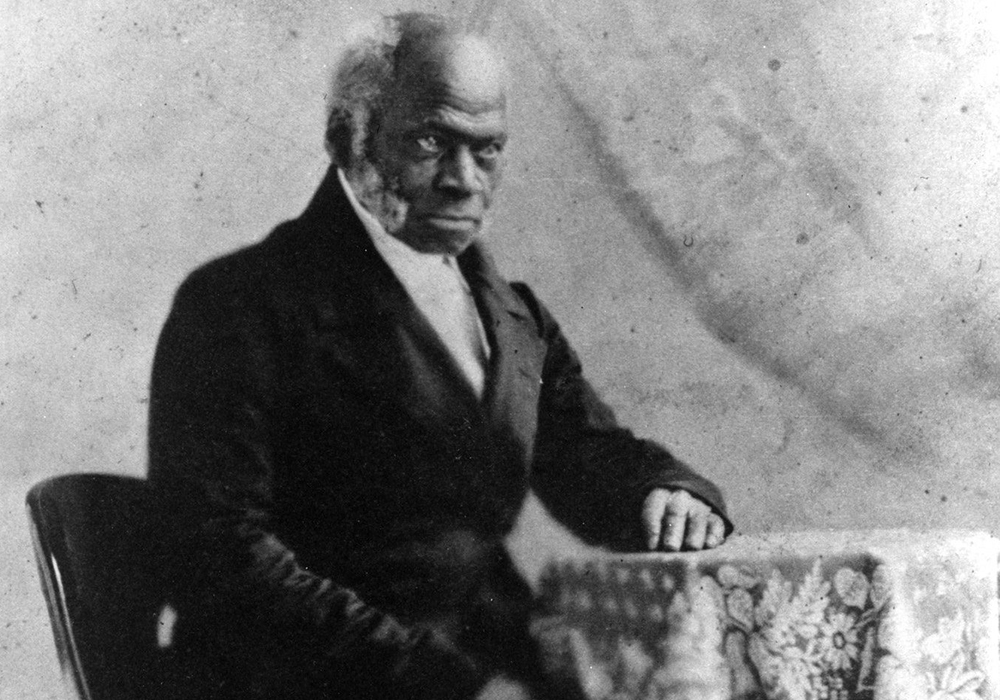

Pierre Toussaint, who was declared venerable in 1997, is pictured in an undated file photo. Toussaint died June 30, 1853, at age 87. (CNS file photo)

Pierre Toussaint was born enslaved in Haiti and was freed in 1807 after his owners moved to New York City. He later prospered as a hairdresser in the city and used his funds to purchase the freedom of both his sister and future wife. He was known across New York City for his many acts of charity on behalf of the poor. Not content with a life of daily Mass attendance, Toussaint spent hours in service to the sick and outcast of the city. When he died in 1853, the streets filled with those impacted by his ministry. Toussaint is the only layman to be buried in the crypt at St. Patrick's Cathedral.

Henriette Delille, who founded the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans in 1842, is depicted in a stained-glass window at St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Henriette Delille experienced a religious conversion in 1834 and was confirmed. Her prayer book expressed her faith journey: "I believe in God. I hope in God. I love. I want to live and die for God." Feeling a call to religious life as an African American was not simple; she was rejected by two congregations. Undeterred, she and two of her friends founded the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, later known as the Sisters of the Holy Family.

The community followed rules as outlined by Delille. The sisters taught, worked among, and assisted enslaved and free children and women in New Orleans. According to Black Catholics on the Road to Sainthood, they "brought into their home elderly, infirm women, a first in the United States."

Augustus Tolton was born in 1854 to enslaved parents in Missouri. His mother, Martha Jane Chisley, escaped slavery's horrors by rowing a boat across the Mississippi River as slave catchers and vigilantes fired upon the fleeing family. Growing up in Quincy, Illinois, young Augustus felt a call to the priesthood, but found the doors closed shut. He persisted, and finally his application was accepted to a seminary in Rome.

Fr. Augustus Tolton is pictured in an undated photo. Born into slavery in Missouri, he was ordained a priest April 24, 1886, in Rome and said his first Mass at St. Peter's Basilica. He is the first recognized African American priest ordained for the U.S. Catholic Church and is a candidate for sainthood. (CNS/Courtesy of Archdiocese of Chicago Archives and Records Center)

Assigned to serve in Illinois, Tolton faced a hard road, as a fellow white priest referred to him as a "[slur] priest." A door opened when he was invited to serve in Chicago. He developed St. Monica's, an all-Black church on the South Side. Tolton spent countless days serving Chicago's poor, walking the neighborhoods, alleys and even bars to listen, serve and work among the outcast of the city.

An image of Mother Mary Lange, foundress of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, is seen in a stained-glass window in the chapel of the religious order's motherhouse near Baltimore on Feb. 9, 2022. (OSV News/CNS file, Chaz Muth)

Mary Lange was born in Cuba and eventually settled in Baltimore, Maryland. Finding a home among other Black Catholics there in the 1810s, she saw education as a way forward for enslaved and freed African Americans. With support of local Sulpician Fr. Father James Joubert, Mary Lange founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence. This order was the United States' first successful congregation for African American women. Their ministry of service to the oppressed has resounded through the years, as thousands of Black Catholics in Maryland have better lives due to the work of the Oblate Sisters of Providence. Lange and the Oblate Sisters proudly wore religious habits at a time when many whites believed Blacks did not even have souls.

This image of Julia Greeley, a former slave who lived in Colorado, was created by iconographer Vivian Imbruglia, who was commissioned to do the painting by the Archdiocese of Denver. (OSV News/Courtesy of Denver Archdiocese/Vivian Imbruglia)

Julia Greeley was born enslaved in Missouri and was freed in 1865 after the Emancipation Proclamation. Still, her body bore marks of the violence of slavery, including a drooping eye, which was the result of a beating, according to OSV News. In 1879 she and the family she served as housekeeper moved to Denver, Colorado. In Denver, Greeley became Catholic and, as a devotee of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, embraced daily service to the poor. She was often seen pulling a red wagon full of food, clothes and medicine for those in need, known as the "one-woman St Vincent De Paul Society." Greeley died in 1918 on the feast of the Sacred Heart. Her funeral was attended by nearly 1,000 people.

Thea Bowman was born in 1937 in Yazoo City, Mississippi. When the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration opened a Catholic school in Canton, the town where she grew up, Bowman's parents saw education as a road to their daughter's self-determination. Upon attending the school, Bowman was captivated by the love and joy of the sisters and decided to join the order. Her devotion to Catholicism and Black identity is the enduring hallmark of her ministry.

Archival photo of Franciscan Sr. Thea Bowman (OSV News/Courtesy of FSPA Archives)

Through song, teaching, preaching, prayer and example, she brought "my Black self," "fully functioning," into the church. Bowman's signature moment was her 1989 speech to the U.S. Catholic bishops. As a faculty member of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana and key voice in the hymnal, Lead Me, Guide Me: The African American Catholic Hymnal, she has made her mark on African American Catholicism.

It is worth nothing that the final document of the 2024 Synod of Bishops acknowledges the sins of racial prejudice, the need to heal wounds and the work of reconciliation. Part of this healing could be official recognition of the gifts of holiness and service of the "Saintly Six" through their canonization.