A June 22, 1865, photograph by John Adams Whipple shows the National Congregational Council at Plymouth Rock. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In his Substack post last week, Ryan Burge looked at some of the data Lewis Frederick Weis gathered in the 1930s about the clergy in colonial and revolutionary America. This isn't survey data. Weis did not find a way to ask the long-deceased clergy questions about their politics or consumer habits. Nonetheless, there are some important things to note that many people forget when discussing the legacy of religion on American life.

Most of the data looks at the years 1763-1783, that is, from the close of the Seven Years' War, or as it is more commonly known in the U.S., the French and Indian War, through the Treaty of Paris which ended the American Revolution. Those dates make sense politically. The situation of the colonies with the mother country was never the same after the Seven Years' War removed the threat of French aggrandizement from the British colonies, as well as the massive debt the war saddled on Britain. And, the new country birthed by the Treaty of Paris would have to find creative political and legal solutions to the issues of church and state once the British king was removed from the U.S. Constitution.

What most jumps out in the data is the preponderance of clergy in New England and belonging to the Congregational denomination. Massachusetts boasted the highest number of clergy with 890, followed by Pennsylvania with 805. Next up was Connecticut with 560 clergy and New York with 310. The most populous colony in 1770 was Virginia, with 447,061 people, but it ranked fifth for the number of clergy, with only 291 ministers. Connecticut, which was third on the list of ministers, ranked sixth in terms of population.

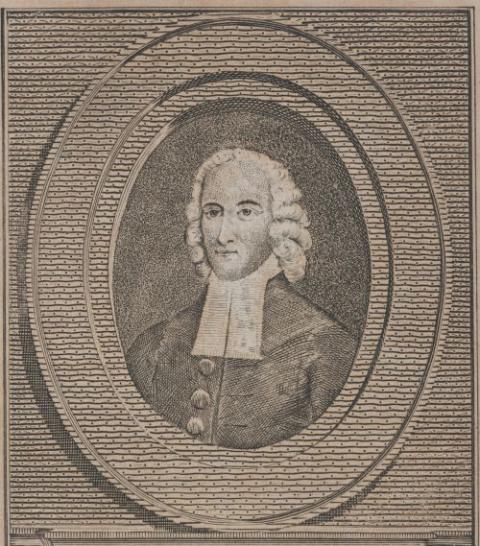

Jonathan Edwards delivered the sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" in 1741, This portrait is by Amos Doolittle. (National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution)

There were 1,380 Congregational ministers in these years, compared to only 660 Episcopal ministers. Far behind were the Baptists at 444 ministers and Presbyterians with 403, followed by German Reformed, Lutheran and Dutch Reformed, at 310, 281 and 160 respectively. No other denomination had more than 100 clergy and Catholics are not even on the list.

These numbers explain why it is never wrong to say that the Puritan influence persisted as the dominant cultural influence on American morals and religious life into the early 19th century. There were divisions with the Congregational establishment in these years, arising from the religious revolution known as the Great Awakening, which is usually dated from the sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" preached by Jonathan Edwards at Enfield, Connecticut, on July 8, 1741. The Congregational establishment divided between new lights and old, and the politics of Connecticut during the American Revolution was shaped significantly by that divide. But Calvinists and the Congregational Church remained the established church in Connecticut until 1818. Congregationalism would remain established in Massachusetts until 1833. New Hampshire required representatives in its legislature to be Protestant until 1852.

Advertisement

These establishments were not as strong as they seemed. Yes, all citizens paid for the upkeep of the established church in their town and for the minister's salary. But when Calvinism broke into denominations, something bizarre happened. The Protestant religion that had stood, above all else, for the sovereign will of God, found itself at the mercy of the many sovereign wills of those who invoked the Calvinistic God. As University of Notre Dame historian Brad Gregory demonstrated years ago in his book The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society, as I wrote in my review, "the competing truth claims of the different Reformers, and their inability to find a nonsubjective basis for assessing the claims they all put forth on behalf of sola scriptura, led first to the relativizing of religious doctrines and, when reason was invoked to clear up the squabbles, and after it enjoyed its eighteenth century heyday, reason too found it[self] in the dock, charged by Marx, Nietzsche, Freud and Foucault with purporting to a significance it did not deserve."

In her important book, Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society and Politics in Colonial America, New York University's Patricia Bonomi analyzed the relationship of religion and politics in these same late colonial and revolutionary years. She recounted how revivalists posited a different understanding of authority from that which they had inherited. Revivalists rooted their appeal in the personal experience of conversion by the individual believer. Politicians took note and Calvinism found itself, not for the first time, allied with anti-establishment politics.

This photograph of a Congregational church is from the album "Views of Charlestown, New Hampshire" by Gotthelf Pach at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. (Smithsonian)

Denominational lines were more porous than the denominational data suggests. For example, Methodism is not listed on the data chart, but it grew out of the revivalist spirit within the Church of England during these same years.

One point Burge makes needs an amendment. He writes, "If you are looking for the remnant of Congregationalists in the United States it's the United Church of Christ." That is, quite literally, half true. If you make your way around New England, in the center of the oldest part of the town is usually a church named "First Church of Hartford" or whatever the name of the town is. A little more than half of these are indeed a United Church of Christ. But, many in the 19th century adopted Unitarianism. So, for example, if you visit the First Church in Quincy, Massachusetts, where the Adams family worshiped, or the First Church in Brooklyn, Connecticut, you will find they are Unitarian, not United Church of Christ.

As we continue to debate the role of religion, and specifically of Protestant Christianity, in the American story, it is important to look back to the historical roots of the discussions. Burge writes: "I frequently wonder if we plucked one of those Christians out of their time period and dropped them into the 21st century American landscape, if they could make any sense of things." The reverse is also true. Those, today, who breezily invoke "the Judeo-Christian tradition," as if it was a univocal thing, misunderstand their history (and likely their theology).

What is clear, as I have noted before, is that during the time of the founding, America was not "a Christian nation" in any meaningful sense of the word, but it was very much a nation of Christians. Religion was in the air people breathed. Its effects on the culture were multifaceted because religion was itself varied and diverse. In America, the search for identity almost always begins and ends in the plural.