A statue of Baltimore Archbishop John Carroll, the first Catholic bishop in the United States and founder of Georgetown University, is seen on the Jesuit-run school's Washington campus March 3, 2022. Documents show Archbishop Carroll owned at least two slaves. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

In 1838, in an effort to stabilize the finances of Georgetown University, the Jesuits who ran the place decided to sell 272 slaves who worked on their Maryland plantations.

Fast forward to 2015. New York Times reporter Rachel Swarns gets a call from a colleague in the business section of the paper with a tip. [Full disclosure: Swarns is an old friend from my days living in Washington, D.C.] That colleague had heard from a Georgetown alumnus who was unsuccessful in trying to get to the bottom of the story about the slaves. Swarns had recently published her book, American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama, so it made sense for her colleague in the business section to go to her with the Georgetown story.

The next year, Swarns published her first story about the Georgetown slave sale and about the descendants of those slaves. She posed what she termed "a particularly wrenching question," namely, "What, if anything, is owed to the descendants of slaves who were sold to help ensure the college's survival?"

On June 14, Swarns came to the Hill Center in Washington, D.C., to discuss her new book, The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church, which grew out of her research. She was interviewed by University of Pennsylvania historian Marcia Chatelain. It was in that discussion that Swarns explained how she came to write the book, and much else.

Rachel Swarns, left, discusses her book The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church in conversation with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Marcia Chatelain at Hill Center at the Old Naval Hospital in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy of Hill Center)

Swarns explained that she found many people were uncomfortable discussing slavery and its ugly history. "I wanted to write a compelling story," she said, and did so by focusing the book on a particular family, the Mahoneys. The matriarch had been a free Black woman who had her freedom stolen from her in the late 1600s. In the 1838 sale, one of the family members escaped but the rest were sold into the harsh conditions of plantation life in Louisiana. Their descendants are now scattered throughout the world and were reunited in a way by Swarns' work.

In her discussion at the Hill Center, Swarns made clear that "the priests believed the slaves were people with souls and that they [the priests] had a responsibility to nurture their souls. Yet, they also believed they could own and sell them." Some priests even speculated that the slaves would be better off in Louisiana because there were so many Catholics there compared to other parts of the South. Perhaps this merely served to salve their consciences, for they were aware of the brutal conditions that awaited the slaves.

This is one of the great values of history when it is well done: It allows us to see how otherwise decent people were capable of moral enormities. It invites us to wonder what moral enormities we ignore in our own day. Listening to Swarns discuss the priests' rationalizations, I couldn't help think of those pro-choice advocates who object to laws that bar elective abortions once cardiac activity can be detected, around six weeks. They note, correctly, that at six weeks a woman might not even know she is pregnant. Whatever the medical significance of the cardiac activity, most of us still consider the presence, or absence, of a heartbeat as an indication that life is present in most other contexts. When people use one fact to obscure or detract from a complicating different fact, that is when they have taken their first step towards being able to overlook a moral enormity in their midst. The Jesuit priests, commenting on the presence of Catholics in Louisiana, perfectly illustrate the phenomenon in their time. What in our day acts in a similar way?

Advertisement

Unearthing this history is not easy work. Many slaves were legally barred from learning to read or write, so their histories were passed down orally. It was the enslavers, the owners, the people with power, who were able to write the history of these times. Still, there were "bits and pieces" of the slaves' stories scattered around, according to Swarns.

The publication of Swarns' book comes as Georgetown University recently announced the first grants from its fund established to help the descendants of the 272 enslaved persons sold by the school in the early 19th century. Working with an advisory committee of descendants, and a committee of students, the school awarded $200,000 to five projects, including health and legal clinics, after-school and pre-college programs, and efforts to memorialize and produce local histories.

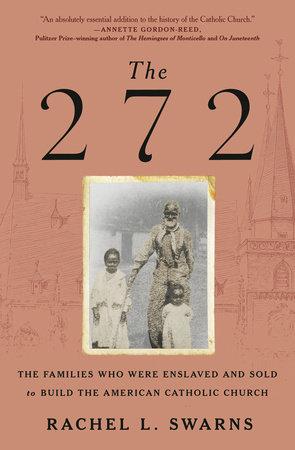

Book cover for "The 272"

One of the other people in the virtual audience for the discussion at the Hill Center was William Collinge, retired professor of theology at Mount St. Mary's University in Emmitsburg, Maryland, and editor of the third edition of the Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. After the discussion concluded, I emailed Collinge to ask what he thought of the event.

"Well, I'm a Georgetown alumnus, and I knew nothing about this when I was a student there," Collinge said. "At that time, Georgetown was only gradually desegregating. I never met a Black undergraduate until I was a senior. I've learned something about the 272 in recent years, of course. In fact, in 1837 Bishop Eccleston of Baltimore urged the Jesuits to sell all their slaves and landed property and buy Mount St. Mary's!"

He added, "The larger history of the Catholic Church and slavery is, as Ms. Swarns said, something Catholics are too little aware of. Perhaps I owe something of my education to 272 people bought and sold as property."

I can't review Swarns' book without reading it, but after Wednesday night's discussion, that book got put on the "must read" list.