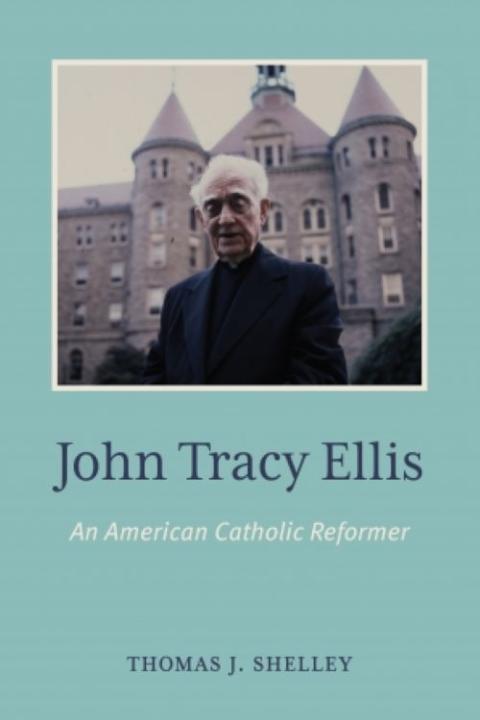

Msgr. John Tracy Ellis (1905-92), known as "dean of American church historians," was a professor of church history and theology who taught at the Catholic University of America 1938-64 and 1977-89. John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer, a biography by the late Thomas Shelley, was published in June. (Courtesy of Catholic University of America, University Libraries, Special Collections)

Msgr. John Tracy Ellis was known as "dean of American church historians," an unofficial title that captured both his stature and his longevity. When he began his studies, church history was mostly apologetical in character, and many in hierarchy preferred it that way. More than anyone, Ellis, who died in 1992, insisted that historians tell the truth as they found it. His career spanned most of the 20th century and so his career was of more than scholarly interest. Ellis became a counselor to bishops and cardinals, too.

A biography has now been brought forward, John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer, by the late Thomas Shelley. The biography contains wonderful information about Ellis' early years. He would often, as Shelley notes, proudly tell people that he was "born and raised on the prairies of Northern Illinois," specifically, the small town of Seneca. His father, Elmer, ran the local hardware store and was a Methodist until he met Ida, Ellis' mother. Interestingly, Shelley says Ellis "described his mother as 'correct' rather than especially devout in the practice of her religion."

John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer by the late Thomas Shelley

Ellis, born in 1905, attended his local parish school, and then St. Viator's Academy and College in a nearby city. Like many schools at the time, it combined the last two years of high school with a four-year college program, and it was tiny, underfunded and lacking in intellectual rigor. Still, it is where Ellis first developed an interest in history. Interestingly, among the small school's other alumni were two men who would make major contributions to the life of the church in the United States: Bernard Sheil, who would become Chicago Cardinal George Mundelein's auxiliary bishop and right-hand man, and Fulton Sheen, who would become a major television personality and archbishop.

In 1927, Ellis secured a Knights of Columbus scholarship to attend the Catholic University of America, where he found a mentor in Msgr. Peter Guilday, then the country's premier church historian. Ellis completed his doctorate under Guilday.

John Tracy Ellis understood the Catholic faith to be a dogmatic faith living in history, changing and unchanging, but always in the sense of renewal.

He returned to his alma mater to teach, made the "grand tour" of Europe, and then took a position at the College of St. Teresa in Winona, Minnesota. Though larger than St. Viator's, it did not satisfy Ellis intellectually. During his time there he finally decided to become a priest, while still hoping to secure a teaching position at a research university. He approached Winona Bishop Francis Martin Kelly, and explained his situation. "If I understand you correctly, Mr. Ellis, you wish to use the diocese of Winona as a means to your end," the bishop said. Ellis admitted that was true and, much to his surprise, the bishop replied, "Well, I do not see any difficulty in that arrangement." The discipline of church history in the U.S. owes a debt of gratitude to Bishop Kelly!

Ellis attended the Sulpician Seminary, now known as Theological College, located across the street from Catholic University of America. It was home to diocesan clergy studying for the priesthood. The spiritual formation he received was standard for the time, entailing a disciplined life of prayers: "meditation and Mass, the recitation of the breviary and the rosary, frequent recourse to the sacrament of reconciliation, a yearly retreat, and spiritual direction from Father Arand." There was little in the way of intellectual formation at the seminary. On June 5, 1938, the feast of Pentecost, Ellis was ordained a priest at the Chapel of Our Lady of the Angels on the campus of St. Teresa College by Kelly.

It is during his account of Ellis' seminary formation that Shelley displays a distracting habit of including something that tells us more about him than about Ellis. He includes a story about the Beacon Hill grande dame, but it has nothing to do with Ellis and it adds nothing to Ellis' story. It is just Shelley wanting to tell a story he liked. Several times in this book, the reader finds these kinds of commentaries that are distracting and, being so often made, a little annoying.

From 1938 until 1963, Ellis was a full-time history professor at CUA. He would later say that the first 15 years teaching full time were "one of the busiest and happiest periods of my life." He quickly became known for his well-organized and well-delivered lectures, his detailed attention to student papers, and his evident, infectious enthusiasm for his topic.

Msgr. John Tracy Ellis taught at the Catholic University of America 1938-64 and 1977-89. The university is seen from the bell tower of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. (OSV News/Bob Roller)

It was also during this time that he produced a book, Cardinal Consalvi and Anglo-Papal Relations, 1814-1824. Here Shelley makes an observation that is profoundly true and incisive, writing, "As a young priest and historian, who was attempting to write honest Church history in the shadow of the Modernist Crisis, he may have considered Consalvi a kindred soul and a model for the kind of progressive Catholic conservatism that he increasingly came to embrace." Ellis knew history too well to adopt a servile conservatism that failed to see the degree to which the church had changed through the centuries, but neither did he advocate or embrace any idea of Catholicism that was not deeply rooted in the church's finest traditions and most ancient teachings. He simply strove to tell the difference between roots and trunks and branches and fruit, and to do so honestly.

The late Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS files)

Ellis' magnum opus was his two-volume biography of Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons. Like Consalvi, Gibbons became a role model for Ellis as well as an historical subject, but in this case it was Gibbons' Americanism that appealed to Ellis. It is odd that Shelley, who gives a good synopsis of the book, does not engage the issue of Americanism head-on as it certainly has been challenged, and challenged in interesting ways, by scholars like Regis University's Michael Baxter.

Even more strange is how Shelley assesses Ellis' work on Gibbons and Gibbons himself. On one page, he cites approvingly the snarky comment of historian Thomas Spalding regarding Gibbons that "the accomplishments of all forty-three years would need hardly a sheaf of paper for their telling." Shelley adds: "Of course, Spalding was correct." A few pages later, he recounts the June 6, 1911, celebration of Gibbons' 50th anniversary of priestly ordination, an event that drew the president, vice president and chief justice of the United States, among other dignitaries. Did Gibbons dupe them all into thinking he was consequential?

Advertisement

It is true that Spalding [Full disclosure: I also had Spalding as a professor and enjoyed his classes too!] focused on the administrative aspect of episcopal leadership, which was not Gibbons' strength. But it is impossible to deny the role Gibbons played in keeping the U.S. hierarchy together through some intra-ecclesial storms that threatened to tear it apart, to say nothing of his role in combating anti-Catholic prejudice. One can see why Spalding made such a judgment, but Shelley's endorsement of it is simply odd.

In his 1955 talk "American Catholics and the Intellectual Life," Msgr. John Tracy Ellis called on Catholics to invest in intellectual pursuits and raise their numbers and influence in social life. Pictured here is the May 2023 commencement ceremony at Jesuit-run Fairfield University in Connecticut. (OSV News/Fairfield University)

One of the best sections of the book deals with Ellis' many students and colleagues whose careers as church historians he launched and championed, even when they pursued a historiographical approach very different from his own. Historians such as Benedictine Fr. Colman Barry, Jesuit Fr. James Hennessey, and Annabelle Melville, studied with Ellis. Others, like David O'Brien and Jay Dolan, never studied with Ellis, but he was quick to praise their work. These latter scholars wrote "bottom-up" social histories which were quite different from Ellis' biographical and institutional approach, but Ellis appreciated a variety of approaches to history.

Shelley's subtitle labels Ellis "An American Catholic Reformer," but there is no throughline making the case for so labeling him. Only in the latter half of the book does it become explicit when Shelley considers Ellis' famous 1955 talk at a meeting of the Catholic Commission on Cultural and Intellectual Affairs, "American Catholics and the Intellectual Life." In that talk Ellis delivered a clarion call for Catholics to invest in intellectual pursuits because their contributions in this sphere did not equal their numbers or their influence in other spheres of social life.

The reformer thread becomes most prominent in Shelley's consideration of Ellis' long friendship with Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray. Ellis helped Murray in his efforts to get the American constitutional system of church-state separation recognized as a valid juridical arrangement in Catholic theology. The traditional doctrine held that Catholicism should be the state religion when Catholics were in the majority, but should enjoy full toleration when they were in the minority. This manifestly hypocritical standard was justified on the theory that "error has no rights" and the pre-conciliar church still viewed non-Catholics as heretics or schismatics.

Here, however, Shelley is at his worst as well as at his best. He grasps the theme but he gets the chronology wrong, something that drove Ellis mad. Shelley has already considered Ellis' "exile" in San Francisco in the 1960s and '70s, after the intellectual climate at CUA became intolerable. And he had considered the Second Vatican Council in various aspects as well as the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 as the first Catholic president. But, then, Shelley introduces Ellis' important essay in Harper's magazine, in which he collected and curated a series of quotes from American prelates that endorsed the American constitutional system. The problem? That article was published in 1953.

The biggest problem with the "reformer" moniker is that Shelley fails to capture the specific ways it is true. Ellis was a reformer first and foremost because his research as a historian showed that claims the church never changed were demonstrably false. He was not an historian using his craft to advocate for reform, the kind of propagandistic approach he loathed. He was an historian whose research made the case for reform in his time and situation against the semper idem arguments emanating from Rome in the pre-conciliar church. What is more, his reform was always a renewal. Like his hero St. John Henry Newman, Ellis understood the Catholic faith to be a dogmatic faith living in history, changing and unchanging, but always in the sense of renewal. He was a churchman first and last. There was nothing revolutionary in Ellis' outlook or temperament.

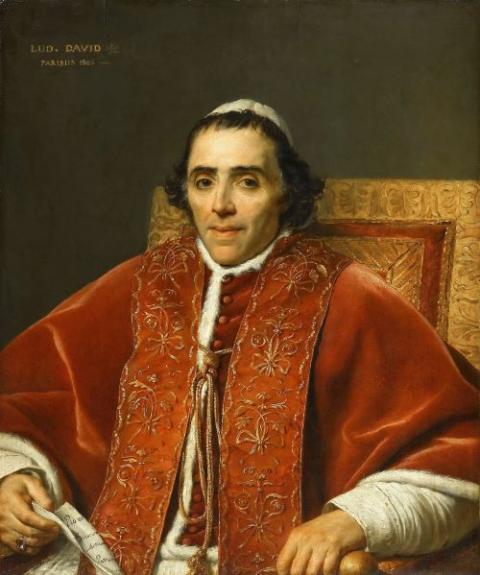

Msgr. John Tracy Ellis gave NCR columnist Michael Sean Winters his print of Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Pope Pius VII. (Wikimedia Commons/Public domain/Jacques-Louis David)

On the wall above my desk, there is a photograph of Ellis at one end, and at the other there is a framed print of Jacques-Louis David's famous portrait of Pope Pius VII. When Ellis, near the end of his life, was vacating his apartment in Curley Hall, the priest residence at Catholic University, and moving to the nearby nursing home run by the Little Sisters of the Poor, he called and asked me to visit him. I assumed he wanted help with some boxes. Instead, remembering I had spoken of my great respect for the pope who had gone toe-to-toe with Napoleon, he gave me this print. It is among my most prized possessions. Every time I look at it, I am reminded not only of the contingencies of church history, but of the wonderful priest who helped me fall in love with the history of the church and taught me how to pursue it.

Editor's note: An expanded version of this review will appear in the spring issue of The Journal of Social Encounters, published online by the Center for Social Justice and Ethics at The Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Nairobi, Kenya, in collaboration with the Peace Studies Department at College of St. Benedict/St. John's University, Collegeville, Minnesota.