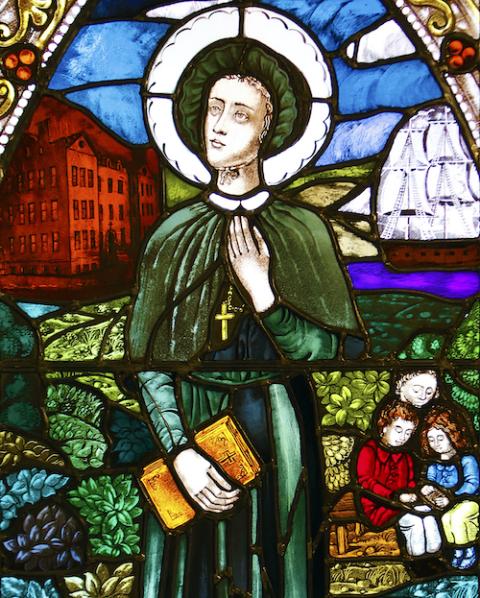

St. Frances Xavier Cabrini is depicted in a stained-glass window at the saint's shrine chapel in the Washington Heights section of New York City. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

What does it mean to be an American and a Catholic? This question Catholics have sought to answer for themselves and for their Protestant neighbors for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Kathleen Sprows Cummings offers a new and thought-provoking interpretation of American Catholic identity and belonging in her book, A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American. Tracing various causes for canonization with the goal of gaining an American saint, Cummings shows that the canonization process revealed how "Catholics defined, defended, and celebrated their identities as Americans."

Cummings' study of the desire for a national saint, or "holy hero," traces various causes for canonization including John Neumann, Philippine Duchesne, Frances Cabrini, Kateri Tekakwitha, Theodore Guerin and Elizabeth Ann Seton, among others. These holy heroes are the central figures of Cummings' work through which she deftly interprets the evolving canonization process, the many personalities involved, and the motivations behind the desire for an American saint. Canonization prior to 1983 was directed through a male procurator, and the American causes for saints developed when the U.S. church had "powerful bishops who could lobby the Holy See in support of American priorities." The various causes championed by U.S. Catholics represented differing American values, but they also served as the potential best chance for success in Rome. Who was the better candidate, Mother Cabrini, John Neumann or Elizabeth Seton?

A cause for canonization is not an easy feat, nor historically a quick process free of political, gender and cultural challenges, as A Saint of Our Own clearly indicates. Seton's cause opened in 1882, but she was not canonized until 1975. Mother Cabrini's journey to sainthood was quicker, beginning in 1933 and ending in 1946 when Pope Pius XII canonized her. Cummings does more than provide insights into the canonization process; she advances our understanding of American Catholic history.

Advertisement

More traditional accounts of U.S. Catholic history have focused on institutional growth, larger-than-life bishops and cardinals, and have traced the growth of an immigrant church to a church-triumphant in the 20th century. These approaches provided a foundation for newer interpretations that consider lived religion and the incorporation of new questions concerning race, gender and power. Must U.S. Catholic history be either institution-building or lived religion? Cummings rehabilitates the traditional American Catholic immigrant narrative as she examines Cabrini's role in the global Catholic Church. Champions of Cabrini for sainthood claimed her as their own, declaring she was a part of the Euro-American immigrant experience. Cummings reminds us that Cabrini as missionary had a larger purpose; Mother Cabrini was a migrant, as were all Catholics born outside the United States. Yes, U.S. faithful have a claim to Cabrini, but so, too, do Catholics in other parts of the globe.

Cummings' examination of Seton's cause, in conjunction with Neumann, who nearly beat the Sisters of Charity foundress to sainthood, shows how gender, politics and inflated egos impacted and delayed sainthood. Seton's cause, opened by Cardinal James Gibbons, was controlled by Vincentian Fr. Salvatore Burgio. He made the cause about himself and his interpretation of Seton within the Vincentian tradition, which did not fit with Seton's real history, her Sisters and Daughters of Charity, and her role in the U.S. church. Efforts to canonize Seton depended upon the cooperation of the Sisters and Daughters of Charity, who split in 1846 following the merge of Seton's Emmitsburg community with the French Daughters of Charity.

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton is depicted in a stained-glass window at the Basilica of St. Patrick's Old Cathedral in New York City. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Cummings reminds readers of the importance of historical memory generally and women religious archives specifically. Seton's religious Daughters examined the real reason for the rift between the New York Charities and the Emmitsburg Daughters, the interference of clerics like Bishop John Hughes of New York and Vincentian Fr. Louis Deloul, chaplain at Emmitsburg. Seton's religious descendants united to further her cause; they, like congregations in the post-Vatican II period, determined for themselves how their holy hero would be remembered. Cummings returns to this point when dealing with other causes offered in the late 20th century, when women religious, influenced by Vatican II theology and feminism, questioned the cost and purpose of the process.

Cummings approaches her study chronologically, beginning in the second half of the 19th century and ending with a contemporary discussion of recent canonizations and potential saints. Each chapter reveals the shifting context and goals of the champions of saints' causes and how these American Catholics saw themselves as members of the Catholic Church and the United States. These identities shifted, starting with the "North American Saints" (Ch. 1) and the broader effort to locate the ideal person to offer to Rome as the first American-born saint. Cummings locates in the subsequent chapters the causes in an American church maturing, finding its strength and claiming a space in the American political landscape from "Nation Saints" to "Citizen Saints" through "Superpower Saints."

The search for an American saint, Cummings argues, reflected the national values at that moment. The final two chapters, "Aggiornamento Saints" and "Papal Saints," and the epilogue explore the impact of Vatican II and Pope John Paul II on the canonization process and speculate the direction of saint-making in the 21st century. Just as the U.S. got its own American-born saint in Elizabeth Ann Seton in the 1970s, American Catholics became increasingly divided over what canonization and sainthood meant, a division that has only deepened into the 21st century.

Who will be the next American holy heroes? Cummings concludes A Saint of Our Own by suggesting possible future-saints, like Franciscan Fr. Mychal Judge and Sister of Charity Blandina Segale, who has already been given the title Servant of God. They "are likely to highlight the complexity of the U.S. Catholic experience," Cummings tells her readers. American Catholic identity was and is a complex and often very institutional-heavy subject. Cummings, however, has provided historians of American Catholicism with a guide toward untangling it by exploring clergy, women religious and the inner workings of church politics, and by asking questions about American identity and citizenship and the importance of memory and historic preservation. A Saint of Our Own is a well-researched and dynamic history, one that will appeal to scholars of history and non-specialists alike.

[Mary Beth Fraser Connolly is the author of Women of Faith: The Chicago Sisters of Mercy and the Evolution of a Religious Community and is currently a continuing lecturer in history at Purdue University Northwest, Westville, Indiana.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.