Los Angeles school workers protest in front of Los Angeles Unified School District headquarters during the first day of a walkout over contract negotiations that closed the country's second largest school system March 21, 2023. (OSV News/Reuters/Aude Guerrucci)

Today is the feast of St. Joseph the Worker, which was the Catholic Church's answer to Marxism's anointing of May 1 as International Workers Day. Pope Pius XII placed the feast date on the universal calendar in 1955, the height of the Cold War. The decision was, in the strictest sense of the term, reactionary.

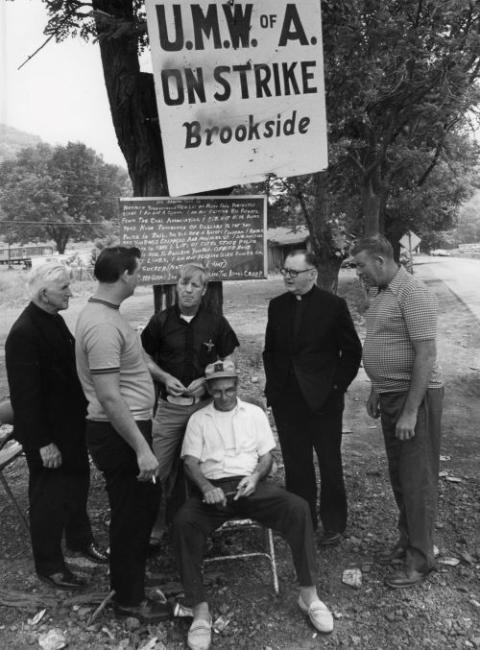

The relationship between the church and organized labor in this country was strong in the 1950s, and so far from being reactionary, it was even visionary. Labor leaders could quote Catholic social teaching chapter and verse. The relationship atrophied a bit during the '80s and '90s as the bishops' public witness increasingly focused on social issues, but in recent years, efforts were renewed to strengthen the alliance anew. For example, last year's May 1 Mass at St. Matthew's Cathedral in Washington, D.C., honored the late AFL-CIO chaplain Msgr. George Higgins. Cardinal Wilton Gregory presided and then-Fr, now-Bishop Evelio Menjivar delivered the homily.

Damon Silvers, who is not Catholic, is a huge fan of Catholic social teaching and was a key player in the three "Erroneous Autonomy" conferences, co-sponsored by the AFL-CIO, where Silvers served as policy director, and the Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies at the Catholic University of America, then headed by Stephen Schneck. Those conferences identified the ways neoliberalism, sometimes known as libertarianism, are a common threat to organized labor and to the principles of Catholic social thought.

Last week, Silvers began a lecture series entitled "Understanding Neoliberalism as a System of Power" at the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose at University College London. Three more lectures will round out the series and I highly recommend anyone interested in Catholic social teaching sign up for them. You can sign up for the May 2 lecture here.

The year 1955, when Pius XII declared today the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker, was not only the height of the Cold War and of Catholic resistance to communism. In the West, it was a time when Keynesianism was establishing solid economic growth and strengthening democracies. Unions not only represented factory workers, but were themselves factories of participatory democracy and social solidarity.

In Europe, postwar Christian democracies were led by Catholics steeped in Catholic social teaching, men like Konrad Adenauer in Germany, Robert Schuman in France and Alcide De Gasperi in Italy. They embraced Keynesian ideas and helped create the European Union. In America in the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower led a Republican Party that had largely reconciled itself to the New Deal and was unafraid to use government to achieve important societal goals such as the interstate highway system. Even right-wing governments demonstrated an authoritarian version of Keynesianism: In Brazil, governed by a military junta since 1964, union membership was mandatory.

Whether you are talking about economics or abortion or climate change, libertarian ideas are simply not Catholic ideas. Period.

In the 1970s, for a variety of complex and particular reasons, from Richard Nixon's decision to end the gold standard to rising oil prices, Keynesianism was challenged anew. A small group of intellectuals – Friedrich Hayek, William Buckley, Milton Friedman, Ayn Rand – had long railed against the Keynesian commitment to state regulation of the market economy, and in 1973 they found a willing political partner in Chile's dictator, Gen. Augusto Pinochet. A powerpoint slide in Silvers' recent lecture featured a photograph of the Chilean dictator meeting with the economist Milton Friedman. Four years later, Angelo Sodano was consecrated an archbishop and named apostolic nuncio to Chile, where he would befriend Pinochet, too. Sodano would become Pope John Paul II's secretary of state and continue to cozy up to neoliberal thugs until Pope Benedict replaced him in 2006.

In his lecture, Silvers made the argument that for too long "too much attention has been paid to what neoliberals said they were doing and far too little to what they actually were doing.” They claimed to be unleashing freedom from the shackles of government. In fact, “they were weakening public power and suborning public power to private power.” Silvers said neoliberalism is “Janus-faced, showing freedom to some and coercion to others.”

Silvers argues that the neoliberal connection with a military thug like Pinochet was not accidental, still less an anomaly. For all its critique of state regulation, and the comprehensive hollowing out of the state's ability to address problems and, indeed, its self-confidence at governance, neoliberalism is all too often content to rely on violence. This same paradox is why libertarians are so comfortable with fascists.

Msgr. George Higgins, second from right, supports striking mine workers in Kentucky's Harlan County in this 1974 file photo. Higgins, longtime chaplain to the AFL-CIO, died May 1, 2002. (CNS/file photo)

To take control of the political economy of a nation, the first target is always the trade union movement. They knew they had to smash unions, not co-opt them. "Trade unions were the political power behind the rise of Keynesian social democracy," Silvers said. He pointed to the role of Reagan's breaking the air traffic controllers' strike early in his first term and Margaret Thatcher's refusal to negotiate with striking miners in 1984 in the United Kingdom as key moments when organized labor was attacked by neoliberal politicians.

The rise of neoliberalism has not brought increased freedom. It has brought increased income inequality, the emergence of powerful global systems for exploiting labor and extracting natural resources, and the rise of tax havens. Most frighteningly, Silvers argued, neoliberalism results in "nominally democratic political systems taking on the characteristics of plutocracies," Silvers said.

The lecture was brilliant, and Catholic thinkers should pay attention. Groups like the Napa Institute have been eager to baptize neoliberalism, but it can't be done. Whether you are talking about economics or abortion or climate change, libertarian ideas are simply not Catholic ideas. Period.

Advertisement

"In these lectures I hope to contribute to a conversation about the global impact of neoliberalism, a conversation that in many ways has been shaped by Pope Francis," Silvers told me in an email. "The Holy Father's emphasis in Laudato Si' on the ways in which both the crisis of climate change and the crisis of global poverty arise out of an idolatry of markets is really a critique of neoliberalism as a global system. In these lectures I hope to expand on those points and also to explore the paradox of libertarianism — that it leads to and is intertwined with authoritarianism."

As Catholics and as Americans, we need to pay attention to that paradox and do everything we can to hasten the end of neoliberalism and restore the kind of postwar political economy that brought widespread prosperity and governments capable of addressing the problems and the challenges of our time. In most, but not all, areas of public policy, President Joe Biden has been restoring the values of solidarity, the common good and human dignity to our politics. Catholic social teaching and its secular sibling, Keynesianism, are not perfect, but they are the best forms of political economy we have ever seen in the West. Finding new, creative ways to strengthen public power can only help poorer countries in the Global South resist the power of multinational corporations that so often rape their economies.

There is much more to be said on this important topic. I look forward to learning more from Silver's lectures. You should, too.