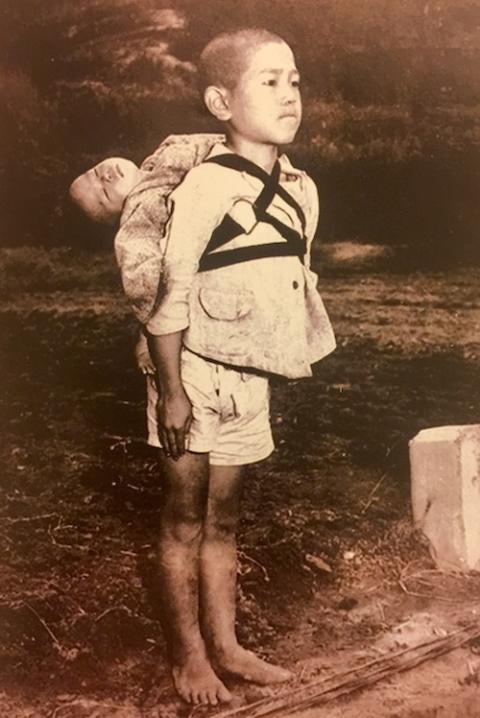

This 1945 photo taken after the atomic bombing in Nagasaki, Japan, shows a boy carrying his dead brother on his back as he waits his brother's turn to be cremated. (CNS/Holy See Press Office/U.S. Marine Corps/Joseph Roger O'Donnell)

(Unsplash/Dan Meyers)

Throughout the night of Aug. 6, 1945, Jesuit Fr. Pedro Arrupe walked the streets of Hiroshima, surveying the damage from a novel bomb that American pilots, freshly blessed by their Catholic chaplain, had dropped on the Japanese city. The spectacle was "awful beyond words," Arrupe later wrote in his Hiroshima diary. Enflamed bodies rushed to the river for relief only to later drown when the tide rose. Small children, their eyes and chests punctured with shards of glass and shattered beams from fallen buildings, wailed for their parents. Overwhelmed by the suffering, Arrupe and his fellow priests brought 150 of the injured to the Jesuit residence just outside Hiroshima, then offered a pre-dawn Mass.

An onlooker might have found the scene baffling — a Spanish priest reciting, Dominus vobiscum, "the Lord be with you," in a setting that appeared terrifyingly devoid of God.

Fifty thousand Japanese perished at the moment of the bomb's explosion. Two hundred thousand died during the following weeks, and many more would lose their lives in the years to come from their wounds and radiation.

Arrupe wrote that rescuers "stayed in the outskirts of the city, and when we questioned them as to what had happened, they answered very mysteriously:

"The first atomic bomb has exploded." "But what is the atomic bomb?" They would answer: "The atom bomb is a terrible thing.'"

Seventy-five years later, this "terrible thing" has increased in number and influence. The world now has more than 13,500 nuclear warheads, most of which fill U.S. and Russian arsenals. Some of these weapons individually contain a greater destructive power than all the weapons used so far in human history. The fearsome facts tell only a piece of the story, the darker part being our faith in this capacity for global suicide — and our tolerance for it.

This dependence on nuclear weapons for our ultimate security as a nation is known as nuclearism. It determines our geopolitics and domestic priorities, usurps local resources, contaminates, sickens, kills and, worst of all, impairs belief in the God of life. Its weapons represent the most extreme form of our death intention, which has existed within human beings ever since Cain killed Abel.

Arthur Laffin's The Risk of the Cross tackles this crisis of faith, finding in the Gospel of Mark a vitalizing and nonviolent theology for reckoning with our nuclear danger.

First published in 1981, the book evolved from a study guide written primarily for Catholic churches in Connecticut. Laffin, a Catholic Worker, co-authored the original version with peace activist Elin Schade and the late Christopher Grannis. Laffin edited this new edition to accommodate new theological insights on Mark, as well as changes in nuclear policy and weaponry.*

Advertisement

This 1945 photo taken after the atomic bombing in Nagasaki, Japan, shows a boy carrying his dead brother on his back as he waits his brother's turn to be cremated. (CNS/Holy See Press Office/U.S. Marine Corps/Joseph Roger O'Donnell)

The book opens with a four-session reflection guide on passages from Mark's Gospel that culminates in a Liturgy of the Word and Eucharist. A collection of informative and well curated articles and resources follow. Arranged thematically in appendices that correlate with each session, these include a personal essay by Robert Aldridge, former defense contractor turned nonviolent advocate, church statements on war and peace, an excellent nuclear weapons timeline, graphs and excerpted pieces documenting the human, economic and environmental cost of nuclear weapons, and reflections on responding as church to the nuclear threat and Gospel nonviolence.

Some of the information terrifies. A partial listing of the many nuclear weapons accidents of the past seven decades provides a rattling reminder of our precarious co-existence with machines that cause immense and multi-generational destruction.

Even a limited use of nuclear weapons, a scenario the Pentagon's 2018 Nuclear Doctrine considers, can have dire consequences for massive numbers of human beings. In an article excerpted in the book, Dr. Ira Helfand, a member of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, writes that a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan would "cause significant climate disruption worldwide" and would affect crop production, interrupt food supply and ultimately result in famine for as many as 2 billion people.

Under nuclearism, human life is neither sacred nor precious.

The dreadful facts could fuel despair were it not for the life-giving theology embodied in Jesus as portrayed in Mark's Gospel. Jesus, the healer and unconditional lover, asks his followers to abandon their "death trust" and risk the cross, exquisitely defined in this slim book. There is no denying that the cross is an instrument of crucifixion, but it also represents an occasion for reconciliation of the human and the Divine, who wants life, not death, for this planet and its people. Jesus, stretched between heaven and Earth, is "a wordless parable of the reign of God overtaking a human heart utterly transforming its frail capacities for love and sacrifice."

This book is an urgent book for our urgent times. Of all the "isms" currently undergoing a necessary reckoning, nuclearism is the least examined and the most perilous. Like the climate crisis, nuclear weapons pose an existential threat and remain an ever-present danger. One wonders why we allow this oppression to continue. The explanations are numerous: ignorance, the desire for geopolitical dominance, money (big bombs bring big bucks), a collective helplessness, or ennui in the face of unfathomable destruction. The Risk of the Cross reveals the deeper dilemma — our misplaced faith. The book's analysis of the nuclear threat through the demanding and relentlessly loving theology of Mark's Gospel shakes complacency and invigorates. It reminds us that long before the "terrible thing," another reality existed: the Lord of life, ever-present to this broken and very precious world.

*An earlier version of this review mistakenly stated the book was in its sixth edition. The original 1981 edition had five printings. The 2020 version is an updated edition.

Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now known as the A-Bomb Dome or Hiroshima Peace Memorial, pictured in contemporary times (Unsplash/Terence Starkey)

[Claire Schaeffer-Duffy, a freelance writer, lives and works at the Sts. Francis and Therese Catholic Worker Community in Worcester, Massachusetts. She and her husband, Scott, co-founded the community in 1987. She has been contributing to NCR since 1999.]

Editor's note: Love books? Sign up for NCR's Book Club list and we'll email you new book reviews every week.