The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, next to Catholic University of America, in Washington. (AP/Jacquelyn Martin)

In February 2012, about a year after John Garvey was named 15th president of the Catholic University of America, Stephen McKenna, chair of the media studies department, was trying to fill a faculty position. After a lengthy search, he and others narrowed it down to three candidates — only to learn the new president had abruptly rejected all three.

According to McKenna, it turned out that Garvey had canceled the search because none of the three finalists openly identified as Catholic. McKenna said that when he visited Garvey's office to discuss the matter, he was lectured on "how to pre-target a desired Catholic candidate, and run a search designed to land that person."

"This was both new and alarming," McKenna told Religion News Service recently in an email. "The policy had always been, 'all other things being equal, hire the Catholic.' Clearly now we were to follow that policy with a wink. We were now to do affirmative action hiring for Catholics."

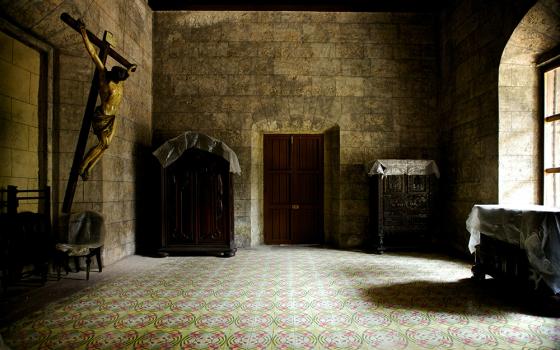

Formally established by Pope Leo XIII in the late 1880s, the university was founded by the American Catholic bishops as a beacon of the faith in U.S. academia. The blue Byzantine dome of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception adjacent to campus is visible from much of D.C., not least from the U.S. Capitol 3 miles away.

Highly regarded for its philosophy and social work departments, CUA today is ranked the 120th best school in the country by U.S. News & World Report, tied with two other Catholic universities, Duquesne and DePaul.

Since Garvey's arrival, however, CUA has become known too for its adherence to what many see as conservative principles, which it enforces with what critics call unorthodox hiring practices and by closely governing aspects of student life. That effort, detractors argue, makes CUA's education mission more difficult, not least by pushing the university into a spiral of declining enrollment and straitened resources.

The university's leaders don't deny their vision for the school includes a staunch Catholic identity, nor do they apologize for their pursuit of Catholic professors. Speaking last year at a forum convened by the conservative Cardinal Newman Society where CUA was lifted up as one of 20 schools that "will truly lead this nation back to God," Garvey noted St. John Paul II's call while pope for Catholic universities' faculties to be majority-Catholic.

Andrew Abela, named provost in 2015 after serving as dean of the business school, told RNS, "There are over 200 Catholic universities, the vast majority of whom do not take their Catholic identity as seriously as we do."

In recent months, the school has drawn attention primarily for its public disputes with its faculty (currently 58 percent Catholic, according to Newman) over a proposal known as Academic Renewal, which consolidates some programs and reduces the number of professors. The changes are necessary, the administration maintains, to tackle the school's $3.5 million deficit, but they have sparked frustration among faculty and led to the creation of a website criticizing various aspects of the proposal. In early June, an informal body called the Faculty Assembly took an unofficial vote of no confidence in Garvey and Abela.

The official Academic Senate, which also includes a smaller group of faculty, recently sent the current version of the proposal to the board, which approved it.

Some observers, though, say the feud is part of a wider confrontation over Garvey and Abela's supposed desire to transform the school into a conservative bastion. The debates over hiring, they say, go beyond ensuring the university's Catholic identity to questions about what it means to be a faithful Catholic.

"Increasingly, hires are inspected by the provost department to see not only whether the person who is proposed to be hired is Catholic, but whether that person is a conservative Catholic," said a faculty member who, like many current and former employees who expressed similar sentiments, did not want to be identified for fear of retaliation.

In a recent editorial about Academic Renewal in the Catholic magazine Commonweal, Julia Young, a graduate and second-generation faculty member at CUA, described a "culture of fear" among the faculty.

"No one — not even senior tenured faculty — wants to speak out, for they risk being fired and being accused of insufficient support for the university's mission," Young wrote.

Advertisement

Sitting in his spacious office in the shadow of the basilica's blue dome, Abela downplayed the accusations. He said he has asked job candidates to pen statements about their Catholic identity up front to "save people who don't think they'll be interested in the kind of university we are from even bothering to apply."

But Abela acknowledged that his "pointed questions" also served to protect the school's profile.

"What I want to understand is, would they be a good mission fit for us?" he said. "Sometimes questions like abortion or the death penalty or religious liberty or immigration will come up, because we talk about the hot-button issues. Catholic University, since we are the bishops' university … we live under a microscope."

At elite Catholic schools, "how Catholic?" has been a topic at least since the 1960s, when, after Vatican II, they began to compete with mainstream institutions. It's safe to say that all of them are committed to a Catholic environment in their hiring; as Richard Conklin, a former vice president at the University of Notre Dame, once observed, "The disagreement comes in deciding how big a thumb on the scale Catholicism should be."

But Notre Dame officials confirmed to RNS that they do not require applicants to make a statement about Catholic identity or to talk about what Abela called the "hot button issues" of faith, even in "free-ranging discussions," as the provost described his approach to job interviews.

Abela strongly rejected any suggestion that CUA gives conservative Catholics preference in its hiring. "Absolutely, vehemently, no," he said. "The claims that we are moving right or somehow moving more conservative are just an attempt to make a caricature of what we're doing."

However, Garvey and Abela have provided their critics with fodder by raising funds from politically conservative, even libertarian, sources. In 2013, the university announced a new School of Business and Economics would be kick-started with a $1 million grant from the Charles Koch Foundation, known for funding conservative political candidates. Over the next three years, the foundation would pledge an additional $11.75 million.

In 2016, Catholic's business school was renamed for Tim and Steph Busch after a $15 million donation — the largest in school history — from the Busch Family Foundation.

Tim Busch, co-founder of the Napa Institute, a group whose views the National Catholic Reporter described as "a mix of conservative theology and libertarian economics," introduced Koch at a 2017 CUA event by saying: "He shares our values. ... I tell Charles he's a Catholic, he just doesn't know it."

Dozens of Catholic priests, theologians and CUA faculty decried the donations. Read one letter to CUA leadership, "You send a confusing message to Catholic students and other faithful Catholics that the Koch brothers' anti-government, Tea Party ideology has the blessing of a university sanctioned by Catholic bishops."

Speaker of the House John Boehner, center left, and Catholic University of America President John Garvey, center right, stand on the east steps of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception during commencement exercises on May 14, 2011. (Bryant Avondoglio/Office of Speaker John Boehner/Creative Commons)

Abela told RNS that both donors understand they have no control over hiring or the content of the teaching. "We, in general, recognize that libertarianism and the Catholic faith are inconsistent, because the libertarian position has a view of the human person that is atomistic, that is completely at odds with Christianity," he added.

"I am not concerned that those donors expect us to agree with them down the line," said Joseph Capizzi, professor of moral theology and ethics at Catholic. "They know that we are a Catholic institution, committed to the fullness of church teaching on social and political matters."

Others remain concerned. "While Catholic social teaching is still present on campus, there's a growing emphasis on libertarian economic policies," Young told RNS. "It feels like the tent has gotten smaller."

Some Catholics may argue that Garvey and Abela are merely holding still in a church that is swaying left since Pope Francis was elected in 2013. Francis' emphasis on matters such as economics and the environment — instead of narrowly focusing on abortion and same-sex marriage — has upended not only expectations but church careers born under his two predecessors, both relative conservatives.

Professors at CUA say their academic freedom also depends on not allowing this incipient split in the church to penetrate too deeply on campus. McKenna noted that such discussions, historically "long and fraught" at Catholic universities, can be "weaponized ... for ideological purposes."

He especially took issue with terms such as "authentically" or "truly" Catholic to describe the school or the Catholic minds it hopes to form.

Capizzi agreed that Catholic identity "is a notoriously difficult thing to define" but said he sees no tension in Garvey's approach to Catholic identity, which balances "being a great, cutting-edge research institution and being one informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition." He added that he "cannot think of a time where (Abela) 'pushed' us not to hire someone we advanced to him."

For his part, Abela seems to believe his vision of a strong Catholic identity improves academic freedom. "I think we are more committed to academic freedom than any other place," he said, "because we are not constrained to political correctness."

It's not clear if younger minds who make up Catholic's customer base share his view. According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, consultants hired in 2016 to assess Catholic's lagging student recruitment recommended the school market itself as a "global Catholic research university" instead of focusing on Catholic identity. (Officials insist the enrollment has improved.)

References to "cultivating Catholic minds" and the school's Catholic credentials were made less prominent on the school's website, and videos CUA played for what Abela described as "prospective donors" at the often conservative-leaning National Catholic Prayer Breakfast about Catholic identity that featured students protesting abortion were placed on other pages.