Pope Francis greets workers as he arrives at the ILVA steel plant during a May 2017 pastoral visit in Genoa, Italy. (CNS/Reuters/Giorgio Perottino)

Next week will mark the fifth anniversary of the election of Pope Francis. New polling data highlight, for me, a principal challenge facing the bishops, clergy and lay leaders in the Catholic Church in the United States: There is an organized campaign to discredit this pope within the Catholic community, and it is meeting with some success.

But today I would also like to look at the degree to which Francis is striking a deep and profound chord with many U.S. Catholics through the lens of Tuesday night's speech by AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka at Seton Hall University.

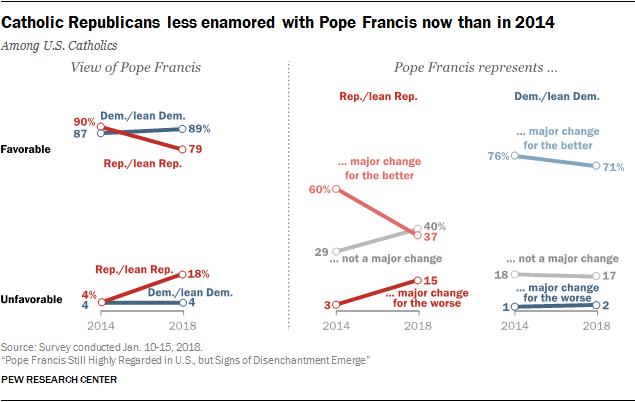

The polling data from the Pew Research Center shows that while Francis' approval rating remains robust, conservative Catholics in the U.S. are less enthusiastic about the pope than they were three years ago. For example, 55 percent of Republican and Republican-leaning Catholics say the pope is "too liberal" now, compared to only 23 percent three years ago. The percentage of all U.S. Catholics who think Francis is a "major change for the better" has dropped from 69 percent to 58 percent. It is not difficult to find the source of that decline: Among Republican and Republican-leaning Catholics, the drop is even more precipitous, from 60 percent in 2014 to 37 percent in 2018.

Commenting on the data, Greg Smith, associate director at Pew, told Religion News Service's Jack Jenkins: "Catholics who are Republican and Republican-leaning have become more negative to Pope Francis. I think this survey shows very clear evidence that Catholic attitudes about Pope Francis have become very polarized along partisan lines."

After years of calling liberal Catholics a variety of derogatory names, such as "cafeteria Catholics" or "Catholics in name only," and insisting that they themselves were "Catholics first," turns out many Republicans are Republicans first and Catholics second, just like the liberals they formerly accused. Everybody seems to be in line at this cafeteria.

Bill Donohue, head of the Catholic League, claims to play the part of knight in shining armor to Holy Mother Church, and is quick to take offense. But he did not question Pew's numbers nor did he, what you might expect from a conservative, point out that the truth of a religious claim is not determined by polling or any social science data.

"It won't be easy for the pope to change these numbers. If a third of Catholics see him as 'too liberal,' and a quarter label him 'naive,' the prospects for him to pivot are not auspicious," Donohue said in a statement, without a word of defense for the supreme pontiff. I have long considered Donohue a blowhard. Now he shows himself to be a fraud.

The new Pew numbers remind me of an exchange between Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich and E.J. Dionne at the University of Chicago last November, in which the cardinal said, "I don't think people are scandalized by the pope. I think they are being told to be scandalized. I think there's a difference."

Bingo. When the nightly EWTN broadcasts and the pages of the National Catholic Register are filled with a relentless drumbeat of hostility to Francis, should anyone be surprised that his poll numbers will begin to drop among the people who turn to such outlets?

This is a challenge for the U.S. bishops. I repeat my specific challenge to Los Angeles Auxiliary Bishop Robert Barron: Whatever reason he had for doing an advertisement for the Register in the first place, in light of these numbers demonstrating disaffection from the pope, why does he not insist that the Register pull down that ad?

Barron is not dumb. He can see how and why these polling numbers are what they are. Why does he permit his good name and apostolic office to be associated with the disturbing — and somewhat successful — attempt by conservative Catholic media to tear down Francis?

Whatever is going on in conservative circles, if you had been at Seton Hall in South Orange, New Jersey, for Trumka's talk about Pope Francis Tuesday night, you would have seen how working-class folk feel about the pope.

(Full disclosure: I played a bit part helping the organizers of this event due to the relationships with organized labor I made when helping Stephen Schneck put together the "Erroneous Autonomy" conferences that were co-sponsored by the AFL-CIO and the Institute for Policy Research & Catholic Studies, where Schneck was director and I was a visiting fellow. I continue minding those relationships now that I am a fellow at the Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life at Trinity College.)

Richard Trumka speaks about Pope Francis March 6 at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. (AFL-CIO/ Gerri Hernández)

All three speakers at the March 6 event — Trumka, Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey, and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy — were repeatedly interrupted by applause as they quoted different statements our Holy Father has made. Among the seasoned church-watchers in the press corps, there was widespread agreement that Trumka understands Francis better than half the bishops and many theologians.

That understanding is deeper than the shared hostility to the paradigms and the policies of neoliberal economics. Trumka grasps the spiritual significance of work in a way our markets do not. He and the workers he represents know what real solidarity looks like, what it takes to build it, and how it is threatened by the wealthy and the powerful, and the ideas they champion.

At the post-event dinner, I got a mix of chuckles and groans when I recalled a speaker at a Napa Institute/Catholic University business school event who cited the greeters at Walmart as an example of solidarity in the workplace. But the solidarity deficit in our society is not a laughing matter, and Trumka's reflections on Francis treated the need to engender more solidarity with the intellectual and moral intelligence the subject demands.

Everyone should read the full text of Trumka's remarks here. Two sections of the talk not only point to the ways the American labor movement and the pope are singing from the same hymnal, but also attest to Trumka's moral leadership. Fifteen years ago, you would not have heard a labor leader speak so passionately in defense of immigrants nor a mineworker talk about the moral urgency of converting to a low-carbon economy.

Unlike the libertarians whose book I reviewed Wednesday, Trumka has not sought to make his religious tradition conform to any political ideology. Instead, he allows his faith to challenge the conclusions his politics previously dictated.

I am sure Trumka does not intend to make the labor movement an arm of the Catholic Church. That is not the point. In our diverse society, there always will be areas where his commitment to workers will put him at odds with the Catholic Church on some discrete issues. The point is that he displays a willingness to reexamine his own presuppositions that is characteristic of a morally serious person in a way too many conservative and libertarian Catholics no longer do.

I would note that the loudest ovation of the night came when Tobin said how proud he was that the U.S. bishops filed an amicus curiae brief supporting the right to organize in the Janus v. AFSCME case. Readers will recall that Ed Whelan, president of the Ethics and Public Policy Institute, suggested that a statement by Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, repudiating the amicus brief was evidence that the brief had been done by the staff of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops on their own, that they had run amok, that the brief did not reflect the will of the bishops.

Advertisement

Tobin is the fourth cardinal I have watched interact with Trumka: Cardinals Cupich, Sean O'Malley and Donald Wuerl all previously participated in one of the Erroneous Autonomy conferences with Trumka. As the title of those conferences suggest, their talks did not show any sympathy for the worldview that informs Mark Janus' lawsuit before the Supreme Court.

Regular readers know that I swim in these church-labor waters pretty regularly. The ideas discussed on Tuesday night, by all three men, were familiar to me from the trenches where I daily work. But as we got in the car for the long drive home, a friend who accompanied me said, "That was really inspiring."

And so it was. At a time of divisiveness and coarseness in our public life, working men and women, as well as intellectual leaders from Seton Hall's campus and religious leaders from northern New Jersey, came together to reflect on what a profound impact Pope Francis has had, and on the challenges to us all that he has posed.

For one night, the conversation was not about tweets and Russian interference in our elections or the latest resignation at the White House. There was hope in that room, and a sense of direction. Sometimes I get depressed by politics in the age of Trump. The event at Seton Hall was a strong rebuke to any sense of resignation in the face of our culture's challenges.

The retail workers and transportation workers and members of the building trades and public sector workers have heard the pope's message and they could not be more enthusiastic. It may not show up in the Pew survey, and I doubt Bill Donohue would care. But I think we are witnessing the start of something important as the labor movement and the Catholic Church make a conscious effort to strengthen their historic friendship anew.

There is solidarity to be forged, and the forging has begun.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.