Amira Musallam, center, is surrounded by peacemakers protecting her on July 31 as she confronts representatives of the Israeli Defense Force, local police and Jewish settlers after the takeover of the home of her in-laws. (Courtesy of Amira Musallam)

The caller on the other end of the line the morning of July 31, Amira Musallam's mother-in-law, was frantic.

Sobbing, she told Musallam how a group of Jewish settlers had just broken through a gate at her home in the West Bank town of Beit Jala, near Bethlehem, forced their way into the house and started indiscriminately throwing family possessions — furniture, lamps, kitchen appliances, clothing — onto the road outside.

The settlers wanted the Palestinian family, Orthodox Christians who hold Israeli citizenship, to move, contending they were on the land illegally.

Musallam hurriedly drove the few minutes from her home to the confrontation in the Al-Makhrour area near Bethlehem. Her concern was not just for her in-laws and her ex-husband, Jad Kisiya, who lived with them, but also for her 9-year-old son Ramzi, who was there.

When she arrived, Musallam saw her son standing outside the house. "He was holding one last toy because all the rest were crushed by the settlers," Musallam said.

She took Ramzi to her mother, returned and called the Israeli police. They arrived, backed by Israeli Defense Forces, but they didn't offer any help.

"They soon arrested my ex-husband for no reason and they gave him a restraining order from his own land," Musallam said. He was later released.

Musallam told the National Catholic Reporter how the settlers, male teenagers with two armed adults, claimed the land belonged to the Jewish National Front, a one-time far-right political party. The police sided with the settlers even though the family produced a court-approved land registration document from May 2023 that allowed them to live there, she said.

Activists and local residents formed a human wall in a nonviolent action on Aug. 8 to push Jewish settlers out of Palestinian land near Bethlehem, West Bank. (Courtesy of Amira Musallam)

That's when Musallam, a 36-year-old Catholic, who holds American citizenship, and has been a nonviolent peace activist since her teenage years, called upon the Unarmed Civilian Protection in Palestine Project. The group works to create a nonviolent response to end the violence between settlers and Palestinians.

Within two hours, 20 people arrived to be a presence alongside the uprooted family. Some, Musallam said, were Jewish Israelis who have long worked as part of an effort to protect Palestinians facing similar property seizures.

Musallam said her colleagues helped ease tensions that day and record what is happening through video and photographs.

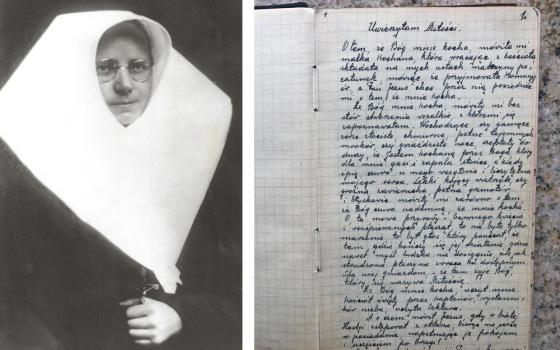

Mel Duncan, cofounder and retired executive director of Geneva-based Nonviolent Peaceforce (Courtesy of Mel Duncan)

Unarmed civilian protection

This effort falls under the umbrella of an emerging global movement known as unarmed civilian protection, or UCP.

Unarmed civilian protection covers a wide range of actions rooted in the concept that training people to respond to conflict through nonviolent means can help protect civilians.

In some cases their efforts have led to negotiated settlements, said Mel Duncan, cofounder and retired executive director of Geneva-based Nonviolent Peaceforce. The organization, founded in 2002, also has an office in Minneapolis.

"I want to be clear that the kind of work we do in terms of civilian protection is one piece of the puzzle of peacemaking. It really focuses on the element of peacemaking and civilian protection. So it creates space for peacemakers to do their work and stay alive," Duncan told NCR.

"We know of at least 60 organizations who are doing some form of unarmed civilian protection in at least 30 areas of the world," he said.

Duncan said the organization had trained people in places such as the southern Philippines, South Sudan, Burundi, Ukraine and even in Minneapolis, following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer while in custody.

While initially the trainers and practitioners often arrive from elsewhere, their goal is to guide local residents in becoming peacemakers themselves.

Advertisement

Minimal church role

Religious institutions have played minimal roles in advocating for unarmed civilian protection efforts, according to Duncan.

While individual worship communities and their leaders, including Catholic parishes, priests and women religious, may take on some role in protection efforts, the work is largely carried out by the people most affected by a particular conflict.

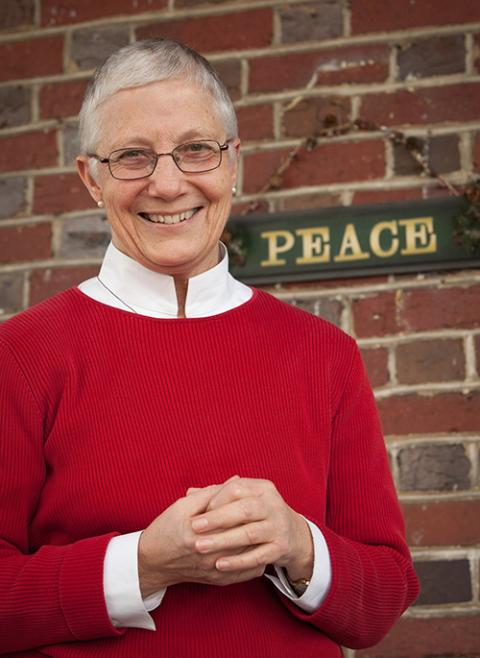

Marie Dennis, senior director of Pax Christi International's Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, is pictured in a 2012 photo. (CNS/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

Marie Dennis, senior director of Pax Christi International's Catholic Nonviolence Initiative, sees these unarmed civilian protection efforts as an example of the kind of creative endeavor that the Catholic Church can embrace. She said it is among the practices welcomed by the Catholic Institute for Nonviolence inaugurated by Pax Christi International in October.

In a visit to El Salvador in the 1980s amid the country's 12-year civil war, she heard that when people from the U.S. or Canada joined a local community they were less likely to be attacked by warring parties.

Cécile Dubernet, senior lecturer and director of the civil peace intervention program at the Catholic University of Paris, has studied this work for the past 20 years.

She is currently leading a program that looks at unarmed civilian protection and the idea that nonviolent action is a viable alternative in a troubled world. The curriculum brings students from Europe and Africa together to discuss the impact of violence on innocent people.

"The European students have much to learn because the African students, they know what [unarmed civilian protection] is," said Dubernet, a member of the French Justice and Peace Commission.

She told NCR she hopes the ideas introduced in the classroom will lead to creative ways to address conflict and improve civilian security in trouble spots.

Cécile Dubernet, senior lecturer and director of the civil peace intervention program at the Catholic University of Paris, is seen in a garden on campus. (Dennis Sadowski)

Looking ahead

Back in Beit Jala, Musallam and others have maintained a regular presence on the land claimed by the Jewish settlers. Early on they had built a solidarity camp that included a small chapel, which, she said, the Israeli Defense Force quickly dismantled.

Amira Musallam, 36, a Palestinian Catholic, has been involved in nonviolent peacemaking efforts since her teenage years. (Courtesy of Amira Musallam)

Musallam was one of a group of four interviewers who traveled to the West Bank in July to gauge interest in a yearlong deployment of at least 100 people trained in unarmed civilian protection techniques.

She said she and her colleagues found overwhelming support for such a step as a means to slow or even reverse the takeover of Palestinian properties by Jewish settlers.

"One thing our assessment group found is that there are at least 22 groups on the West Bank that are doing UCP in one way or another," said Duncan, who also is lead organizer for the Unarmed Civilian Protection in Palestine Project. "More often than not it's Israeli Jews protecting Palestinians."

The group's findings point toward a growing realization that nonviolence can effectively address conflict if given a chance, he said.

"This is an emerging practice. It is happening all around the world. ... So we need to put this forward that this is something that we need to pay attention to and nurture it and provide resources and legitimacy because it is a reasonable way forward if we're going to survive."

'This is an emerging practice. It is happening all around the world.'

—Mel Duncan, cofounder and retired executive director of Nonviolent Peaceforce