By JOHN L. ALLEN JR.

New York

One crucial element in shaping personality is what we might call the “respected other.” By that, I mean the kind of person with whom someone is in deep, sustained conversation, with whom they share a base of values, but with whom they also have important differences. Negotiating this relationship with the “respected other,” balancing one’s identification with it against the continual need to distinguish oneself from it, usually occupies a significant share of someone’s intellectual and emotional energy.

For the quintessential post-Vatican II bishop, this “respected other” was usually secular liberalism. Such bishops found much to admire in liberalism – the instinctive sympathy with the oppressed, the idealism that fuels efforts for social change, the commitment to reason and tolerance in approaching diversity. The dialectic with secular liberalism, the attempt to “baptize” it with the values of the gospel, framed the agenda for many of these bishops. For a classic example, think Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini’s famous exchanges with the novelist Umberto Eco. Such bishops felt more at home in the thought world of, say, the editorial page of the New York Times than with Protestant scriptural literalism, even if they had important differences with both.

For the typical John Paul II bishop, on the other hand, and now the typical Benedict XVI bishop, the “respected other” is instead more often Evangelical Christianity as well as secular cultural conservatism. Such bishops would feel more affinity with an Evangelical Bible study group than, say, the typical religious studies faculty at a state university. Policy wonks among them are more likely to have read the latest titles from Francis Fukuyama or Dinesh D’Souza than this week’s New Republic. They move in the same thought world, and share many of the same instincts – primarily the sense of a basic cultural clash with secularity, and the consequent imperative to defend a strong sense of identity. Yet many are also conscious of potential exaggerations in their “respected other,” such as ghettoization, judgmentalism, and over-concentration on a narrow canon of cultural issues.

The most impressive of this type of bishop manages to blend a robust sense of Catholic “otherness” with openness to the broader culture.

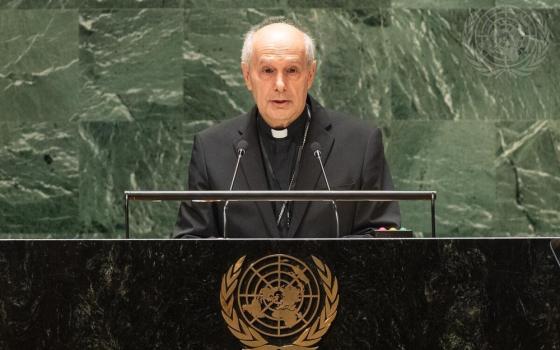

All this comes to mind in light of the looming installation of Archbishop Thomas Collins, 60, as the new archbishop of Toronto on January 30. Collins has served since June 1999 as the Archbishop of Edmonton, and he’s now set to become one of the most visible figures in English-speaking Catholicism, presiding over an archdiocese of one and a half million Catholics. Many Canadian observers compare him to Cardinal Marc Ouellet in Quebec as a striking example of the second kind of bishop described above.

Recently, Collins sat down for an interview with Salt and Light TV, Canada’s Catholic television network. (The segment can be found here: http://www.saltandlighttv.org/prog_slprog_witness.html) The interview was conducted by Basilian Fr. Thomas Rosica, who runs Salt and Light, and who previously served as the coordinator for World Youth Day in Toronto in 2002. Collins comes off as affable, pastoral, and articulate. (He manages, for example, to use the word “globulize” correctly.) Collins is unabashed in his assertion of Christian identity – he talks about Scripture in terms that would do an Evangelical proud, and he also speaks fondly of organizing Corpus Christi processions through the streets of Edmonton. He seems equally committed to constructive engagement with secularity, including the press and political leaders.

Collins is worth keeping an eye on, if for no other reason than that he’s almost certain to be among the next crop of new cardinals, and hence an important force in Catholic affairs at the universal level. A few snippets from the interview follow.

t

On relations with the Press

“Many people involved in the media, particularly the secular media, always have a story to do … they’re doing a fire, they’re doing a bank robbery, they’re doing the bishop, they’re doing something else … they just get one call after another, and they simply cannot be informed about each of these items. Sometimes they’re coming from a perspective where they don’t understand the nuances and the issues. That’s not ill will, it’s just the reality of their work. So, I think it’s important to respond to them and to reach out, to try to help. If there’s any way we can make their work more fruitful, I’m always glad to do that. I also think it’s important because it’s a way of communicating not only with the gathered, but also the scattered. … We need to engage this world, we need to become involved, and the media is one way of doing that.”

On the Movements in the Church

“I’ve sought to try to understand their particular charism, to have all of them speaking to the bishop and, if possible, to have them speaking to one another. They’re a great richness in the church, but we can’t become globulized into this kind of Catholic or that kind of Catholic. The key is that they center in on the parish and the diocese, and that they provide their special gift or their charism for the service of the whole church, and that they not become disconnected from the whole church. What I’d like to do is to reach out to each one of them, and to be sure that they’re part of the whole reality and the fabric of life in the archdiocese. I’m sure that’s what they are.”

On Politicians

“They have a difficult task. Very often people involved in politics are away from their families, they’re on the road, they have a stress-filled life, they need to make decisions quickly. It’s sort of like being a bishop! It’s very much an engaged kind of life. So, I think it’s important for our political leaders to be people after the example of St. Thomas More. He was a lawyer, a judge, a politician, and he’s now the patron saint of them all. He was a man deeply rooted in prayer, his conscience guided his actions. There wasn’t a kind of disconnection there. What a sad thing that would be, to have a disconnection between one’s heart and one’s conscience, and one’s actions. That would be a fractured kind of life. Thomas More really had it all together. He could act wisely as a lawyer, judge and politician. … We should pray for politicians. We should support politicians, encourage people. I’m not talking about this or that political party. There are good people in all the different parties. I think we need to have a ministry to politicians, because of the fact that they have a very busy, stressful life, for their spiritual well-being and to reach out to them. They’re an important part of the flock. Also to encourage people to enter politics, to bring their vision of faith, their integrity, their love for the common good. People enter politics because they want to serve the community, and that’s a very important spirit to keep alive during their whole time as politicians.”

By the way, Salt and Light has launched a new daily webcast called “Zoom,” which offers a brief rundown of the day’s Catholic news. It can be found on their home page at http://www.saltandlighttv.org/