A bilingual voting sign is seen at St. Patrick Church polling station in Norcross, Ga., on Election Day 2020. Exit polls show that views about abortion, an issue Catholic Church leaders have made a priority for decades, do not necessarily motivate Catholic voters. (OSV News file photo/The Georgia Bulletin/Michael Alexander)

In the aftermath of Donald Trump's decisive presidential win, two sobering trends about politics and religion are becoming clear: Religion doesn't seem to motivate Catholic voters, nor do views about abortion, an issue Catholic Church leaders have made a priority for decades.

Trump's improved numbers with Catholics may put to rest the narrative of an evenly divided Catholic electorate. Yet despite movement toward Catholic majority support of the GOP, the election results paint a picture of an American church more fractured than ever, according to analysts who spoke to the National Catholic Reporter.

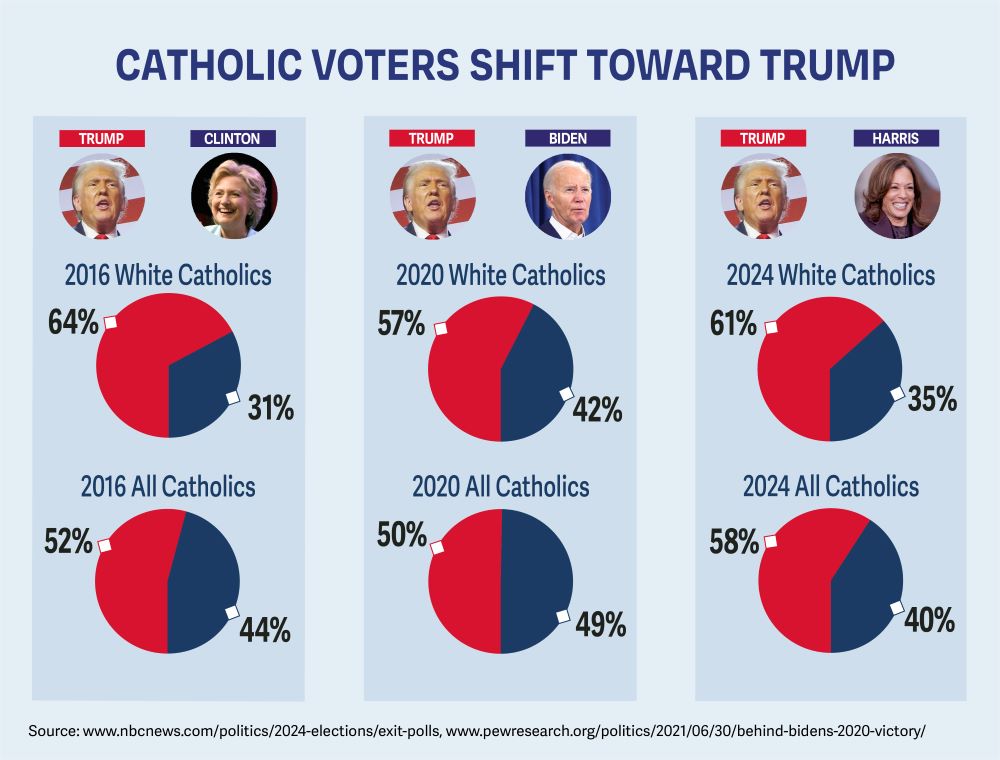

Exit polling confirmed a persistent shift of white Catholics toward the Republican Party, with two surveys showing 61% of white Catholic voters voting for Trump. Overall, as many as 58% of Catholic voters opted for Trump in this election, compared to the 50% of Catholics who chose him in 2020 — an eight-point swing. A pre-election poll by NCR also found Catholic voters in swing states, especially white Catholics, favoring Trump.

These numbers extend the trend of Catholics almost always supporting the presidential winner.

But Catholics have not voted as a predictable bloc since the 1960s. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne famously characterized the pattern of Catholic swing voters with his assertion that, "There is no 'Catholic vote.' And yet, it matters."

Now Dionne sees an even "less distinctly Catholic vote than there used to be," he told NCR. "In a lot of ways, white Catholic voters are behaving like other white voters are."

Trump's win — or more accurately Harris' loss, since while Trump gained almost 2 million votes over 2020, Harris received about 8 million fewer than Biden — is less the result of one group's votes and more about a small but consistent shift by virtually every group of voters.

What drove the shift is the cost of living. "It's very important that we be realistic about how much this election hung on the economy," Dionne said in a post-election webinar sponsored by the Brookings Institution, where he is a senior fellow.

Most commentators have dubbed it an election ultimately about the price of eggs.

(NCR/Toni-Ann Ortiz/OSV News/Brian Snyder; CNS/Reuters/James Lawler Duggan; Reuters; CNS/Matthew Barrick; OSV News/Reuters Photo/Tom Brenner, Reuters, OSV News photo/Reuters/Hannah McKay)

"Religion didn't matter much," said Ryan Burge, an expert on data about religion and politics and an associate professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University.

Although many voters take their religion seriously, it doesn't seem to determine how they vote. Instead, Burge sees a trend in which a voter's political identity is their "master identity," with "everything else living downstream."

Vice President-elect JD Vance could be an example of political identity determining religious identity, rather than vice versa, Burge said. Vance converted to Catholicism after exposure to conservative Catholic groups and individuals that matched his political leanings.

Trump's gains among men of all races and ethnicities also tracks with the growing gender gap in Christianity, which reverses a decades-long trend of women being more involved with faith and religion than men. Burge believes that men who are uncomfortable with progressive social issues might find it more acceptable to attribute their beliefs to religion than to racism, xenophobia or homophobia.

'In a lot of ways, white Catholic voters are behaving like other white voters are.'

—E.J. Dionne

Pope Francis may have inadvertently given some Catholics permission to vote for Trump by equating the two candidates as both "against life" — Harris for her stance on abortion and Trump for his on immigration. The pope urged U.S. Catholics to use their consciences to determine the "lesser of two evils."

Yet neither issue was named as the primary issue of Catholic voters. Instead, like voters as a whole, Catholics put economic concerns at the top of their list.

Abortion not galvanizing voters

Voters sent a contradictory message on the issue of abortion. In the 10 states where abortion was literally on the ballot in the form of state constitutional amendments, measures that protected or expanded abortion access won in seven states. It would also have prevailed in an eighth, Florida — where the amendment won support from 57% of voters, but Florida requires a 60% threshold, rather than a simple majority, to amend its constitution.

In the states where abortion expansion initiatives failed, Catholic dioceses and other organizations had poured millions of dollars into opposition groups. Yet in four of the seven states where voters expanded abortion access, majorities also voted for Trump.

"A lot of people went to the ballot box and voted for Trump and to increase abortion access," said Burge.

And at least some of these pro-choice Trump voters were Catholic. Polls consistently show, as did NCR's, that a majority of Catholics support legal abortion in all or most cases.

"Despite everything the bishops have tried to do to make abortion the Catholic issue, the public opinion polls show Catholics are pretty much the same as everybody else on abortion," Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese observed in a post-election event sponsored by Georgetown University.

Trump's flip-flop on the issue — in which he insisted that he would not enact a national ban and that abortion regulation should happen at the state level — appears to have been accepted by pro-choice voters and pro-life ones alike. On the Democratic side, rhetoric about threats to women's reproductive freedom were not enough to sway voters beyond the base.

"The message of this election is that Republicans are safe pulling back from strong anti-abortion positions," Dionne said. He noted that Trump turned to transgender issues as a replacement culture war issue.

"Going forward, given that Trump has largely abandoned opposition to abortion as a major political theme, it will be an interesting test of pro-lifers as to whether they keep supporting Trump for other reasons, or whether those were their primary reasons to begin with," Dionne told NCR.

A lawn sign produced by Catholics for Freedom of Religion is seen outside Sts. Philip and James Church in St. James, N.Y., Nov. 1. Exit polling confirmed a persistent shift of white Catholics toward the Republican Party, with two surveys showing 61% of white Catholic voters voting for Donald Trump for president. (OSV News/Gregory Shemitz)

Trump's gains among Catholic voters is evidence that Catholics care about "more than abortion," said Jo Renee Formicola, emeritus professor of political science at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. "They also deal with basic issues of everyday life, which for most people is the economy."

That beliefs about abortion are important but not the primary reason for a presidential vote may be especially true for Latinos, says Luis Fraga, professor of political science and of transformative Latino leadership at the University of Notre Dame, where he also directs the Institute for Latino Studies.

Trump's victory continues the trend of the Republican Party peeling off Latino voters from their long-standing commitment to the Democrats — especially among men and those without a college degree. Although Harris held on to a majority of Hispanic voters, exit polls put her numbers in the 52-54% range. In 2020, 59% of Latinos voted for the Democratic nominee, down from 66% in 2016.

The shift is particularly acute among Latino men, a majority of whom went for Trump this year. (Biden won Latino men in 2020, 57% to 40%)

This year's exit polls do not provide data specifically about Latino Catholic voters, except from limited geographic areas such as Miami-Dade County in Florida. But NCR's pre-election survey found two thirds of Hispanic Catholics supporting Harris.

Latino voting patterns are complex, says Fraga, and the group is not monolithic. For some Latinos, immigration is primarily seen as an economic issue, not a moral one affecting their families.

"It has always been the case that there is a subset of Latinos who have very restrictionist views of our immigration policy, but the question is whether that percentage has gone up," said Fraga, who was hesitant to draw conclusions based on early exit polls.

An American flag frames a cross atop Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Cottonwood, Ariz., Oct. 29. The church's parish hall was a polling station for voters in the Nov. 5 election. (OSV News/Bob Roller)

Most Hispanics oppose mass deportations and much of Trump's agenda. NCR's survey found that Hispanic and Black Catholics, as a whole, were more progressive than white Catholics on many issues, including racial justice, abortion rights and LGBTQ allyship.

"Given how much the Trump campaign and Trump himself emphasized immigration — even reaching the point of him talking about immigrants 'poisoning the blood of our country' — one would think that would transcend certain policy views," Fraga said. "Now he's talking about them, or their family or their grandmother."

Fraga also noted the role of misinformation in the campaign, especially on Spanish-language media.

Lingering questions

While conservative Catholics — especially those in political organizations that campaigned for Trump — are celebrating the gains made among Catholic voters, others are concerned about what the election results may signify, especially for an already polarized church.

With abortion no longer a galvanizing issue, and Catholics voting much like the rest of the country, will the Catholic vote matter?

Not only is there no such thing as "the Catholic vote," Formicola said, "there is no such thing as 'the Catholic.' "

"Both of those designations are myths," she told NCR. "There are so many people in the tent of what we call 'the Catholic vote.' It's made up of a coalition of many different kinds of people."

She cites cultural Catholics, so-called "cafeteria Catholics" and practicing Catholics as part of the coalition, in addition to demographic subgroups based on age, gender, geography, income level, race and ethnicity, not to mention liturgical preference, theological beliefs and ideology.

As with political coalitions, collections of such diverse subgroups are not always cohesive. Will the church become synonymous with white Republicans, as the evangelical church in the U.S. has been? For the Democrats, some of the few groups the Democrats improved among were the "nones," atheists and agnostics.

The exodus from religious institutions, which had slowed after decades of rises, may again accelerate in the aftermath of the election, especially among progressives, if Burge is correct about the underlying importance of political identity over religious identity.

"Perhaps the Catholic Church has become more of a cultural identity and a political identity than a religious orientation toward life," Burge said. "Maybe it's always been that."

For all their talk of unity, church leaders face a church more divided than ever.

"While the Catholic vote is becoming more conservative, I really do think some of it is because a lot of cradle Catholics who are progressives no longer identify as Catholic," Dionne said. "You've got two Catholic worlds now that are pulling apart."

Advertisement