A priest wearing a protective mask and gloves blesses a member of his congregation after hearing confession at a Rome church while practicing social distancing March 26, during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Remo Casilli, Reuters)

Young people wait to go to confession outside St. Anthony's Catholic Church in North Beach, Maryland, April 1, during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/Bob Roller)

The social distancing measures imposed on most of the world's population during the coronavirus pandemic have not only prevented Catholics from going in person to celebrate the Mass, but have also largely put a stop to the practice of confession.

This new reality, especially serious for those suffering from the virus or nearing the end of their lives, has revived conversation around a basic question: Why can't we do this by phone?

Several theologians queried about the matter by NCR pointed to concerns about the possible surveillance of electronic devices, which could result in a breach of the seal of the virtual confessional. But they also stressed that the church does not want people to doubt the availability of God's mercy, and has yet to consider the surveillance issue fully.

Msgr. Liam Bergin, an Irish theologian at Boston College, noted that some European governments have been holding cabinet meetings via webcam.

"If it's safe to have a cabinet discussion over Zoom, or some other platform, many of these concerns may no longer be the case," he said.

"I think it's really important to broaden the canvas," said Bergin, who is also a former rector of the Pontifical Irish College. "It's also important to remember that the saving power of God is communicated to us in many, many ways."

Fr. Jason Espinal listens to a penitent's confession during the ongoing coronavirus crisis in the schoolyard of Our Lady of Angels Parish in Brooklyn, New York, March 21. (CNS/Ed Wilkinson, The Tablet)

George Worgul, Jr., a theologian at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, said he thought the prohibition on distance confessions might be a simple issue of the church not yet updating its canons to reflect modern developments.

"I think what you have going on here is you have rules that were created before the technology, and the church simply is not so attuned to changing those regulations because of emerging technology," he said.

"I really don't think it's as much a theological question, because it misses the point," said Worgul, who has focused his work on ritual studies and sacramental theology. "It's not about the confession of sins that's the crucial issue. The crucial issue is God's mercy, and God's forgiveness."

Felician Franciscan Sr. Judith Kubicki, a theologian at Fordham University, agreed. She noted that the church had never before been confronted with a global pandemic in the digital era.

"I'm not sure that anybody has seriously addressed the question enough to give an official answer" about confession by phone, said Kubicki, a former president of the North American Academy of Liturgy. "We haven't seen this. We haven't had this experience."

The question of the possibility of confession by phone has become particularly acute in hospitals, where coronavirus patients are kept in isolation to prevent transmission of the virus and are sometimes unable to receive any visitors, including priests.

The U.S. bishops' conference advised American prelates against allowing confession by phone in a March 27 memo, citing concerns about protecting the confessional seal.

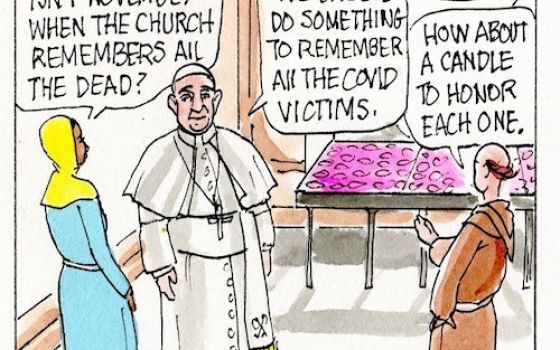

The Vatican had earlier addressed the difficulty in conducting confessions during this time in a March 20 decree making clear that it is acceptable for bishops to offer general absolution to groups of people as deemed necessary.

The decree, issued by the apostolic penitentiary, gave the example of a bishop or priest who might stand at the entrance of a hospital and use the facility's amplification system to offer absolution to those in the building.

Bergin, Worgul and Kubicki each stressed the abundant nature of God's mercy, and the church's teaching that a person who is unable to go to confession can still speak to God directly and request pardon. Pope Francis mentioned this possibility in his homily for his livestreamed Mass from the Domus Santa Marta March 20.

Bergin said that in this time priests "should be reassuring people of God's grace and mercy, as opposed to playing on their fears."

"This is a precarious time, and we should not doubt God's mercy, and God's grace, that's extended to us," he said.

The Irish priest even said he had spoken to one bishop, who told him: "If somebody was in extreme circumstances and they called me to confess their sins and receive absolution, I'd do it."

Making clear that he is not a bishop or a priest, Worgul said he would offer the following advice to a person in an emergency seeking to confess by phone: "If someone really wants to confess their sins and experience God's mercy, and the best way to do this is a phone call or a video conference, do it."

"Then after the crisis ends, if you feel like you have an obligation to go to confession, then do that," the theologian suggested.

"To go the other way, to talk about whether this phone conversation is valid or are the sins really forgiven, is to really miss the point about God's mercy and love," he said.

[Joshua J. McElwee (jmcelwee@ncronline.org) is NCR Vatican correspondent. Follow him on Twitter: @joshjmac.]

Advertisement