(Unsplash/Kelly Sikkema)

The Pharisees and scribes who gathered around Jesus in today's Gospel reading were like fastidious amateurs who watch figure skating solely to note each flaw or ungainly gesture. In today's Gospel, these experts in righteousness focused on the disciples' disgraceful deficiency in handwashing practice. Of course, a critique of the disciple was an implicit disparagement of the teacher.

Jesus knew nothing about germ theory. Perceptive as he was, we can rest assured that he never saw a microorganism. When he lambasted the delegation from Jerusalem, Jesus remained focused on faith and integrity, not hygiene.

As so often happens, especially in matters of religion, the Pharisees' problem sprang from good practices that went awry and took on a life of their own. According to Jewish tradition, God gave Moses the law as a guide to help humans fulfill their vocation as collaborators in the work of ongoing creation.

As we hear in today's first reading, the law pointed out the path to life and outlined the plan for establishing a holy nation. Observance of God's law would form the desert wanderers into a community that demonstrated the goodness of the God who called them into being. The law was essentially a blueprint through which the people of God would know how to further God's plan for all people. By collaborating with that plan, they would enjoy communion with God.

That was the plan.

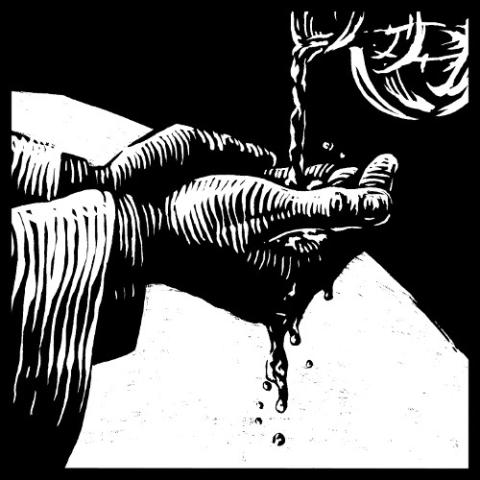

But that plan fell under the influence of competitive, scrupulous, self-righteous, legalistic human beings. In other words, it got interpreted by the likes of you and me. With the best intentions in the world, wise people developed customs and practices designed to safeguard the law by interpreting how it should be put into practice in everyday situations. From the command to keep holy the Lord's Day, there grew precise instructions about just which activities were and were not permissible on the day of rest, right down to the detail of when a candle could be lit. Exodus 30 and 40 taught that priests should perform ritual ablutions (Exodus 30:18-21, 40:31-32).

Based on that, teachers developed practices to guarantee ritual purity for everyone — requirements that not everyone could fulfill due to their work circumstances, their health or their gender. The law, which was designed to be a path of holiness for all people, became distorted. People who wielded the power of interpretation developed precepts that effectively segregated the community. Those who had the wealth and free time to act holy could cite religious reasons for avoiding the unclean and sinners whose touch or presence could contaminate them and their sanctuaries.

Jesus understood the law as a divine plan to bring humanity into union with God and with one another. Few situations moved him to anger like the hypocrisy of people who distorted the law's intent. Obviously, the problem was not unique to first-century Pharisees. Every human society and every religious tradition is prone to promote self-serving elitism and exclusion of those labeled as "the others." In-group cohesion and self-ascribed status are the rewards for such discrimination.

(Mark Bartholomew)

Jesus responded to the purity police by citing the prophetic tradition. His quote from Isaiah was an indictment of their motives for scrupulous scrubbing. He might as well have said: "Is washing a humbling sign of your need to be cleansed from sin or a purity show? If you think clean fingernails are all you need to walk worthily in the presence of God, your hearts and your heads are in the wrong place!" In our liturgy, handwashing accompanies a prayer to be cleansed from sin.

This leads us to consider our own pious practices. How sincerely do we pray the Confiteor during our penitential act? Do we honestly admit our willful wrongdoing and avoidance of doing good? What if we took our penitential act as seriously as people in recovery take 12-step meetings? At the beginning of each meeting, the participants introduce themselves as addicts. They go on to talk to one another about their failures and their attempts to avoid remaining trapped in destructive behavior. How would our faith communities change if we looked one another in the eye while saying, "I am a sinner. I need your support and your prayers!"?

Jesus critiqued his critics for keeping their hearts far from God. They lacked the integrity to admit their weakness, thereby blocking God's saving grace from touching their hearts. A heart that protects itself from admitting weakness cannot know God because it has deified itself. We cannot mend our hearts solely by our own efforts. Fixing our hearts is a matter of will and grace. The grace is available through the law and the prophets, the Son and the communities led by his Spirit. Do we have faith that makes us willing to accept our need for help?

Advertisement

[Mary M. McGlone is a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet who is currently writing the history of the Sisters of St. Joseph in the U.S.]

Editor's note: This Sunday scripture commentary appears in full in NCR's sister publication Celebration, a worship and homiletic resource. Sign up to receive weekly Scripture for Life emails.