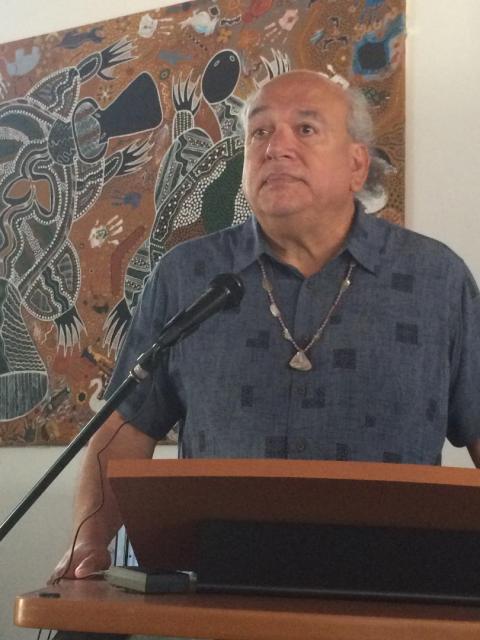

Retired Bishop Francis Quinn of Sacramento, California, the oldest Catholic bishop in the United States, died at age 97 March 21, 2019, at Mercy McMahon Terrace assisted living center in Sacramento. He is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS/Courtesy Diocese of Tucson, Arizona)

Francis Quinn, who retired as bishop of Sacramento, California, in 1993, and who spent the next 13 years ministering to indigenous communities in Arizona, died March 21. He was 97.

Quinn was known as a critical thinker and a caring pastor who supported the Gospel's preferential option for the poor. He frequently ministered to the homeless on the streets of Sacramento.

Quinn was also a gifted writer. As editor of The Monitor, San Francisco's archdiocesan newspaper, his liberal views often ruffled conservative Catholics.

"Yes, I upset them, but it was a joyful job," Quinn told Sacramento's Capital Public Radio (CPR). "We never came to blows."

At age 93, he published a fictionalized autobiography titled Behind Closed Doors: Conflicts in Today's Church, dealing with the struggles of priests in today's church. "I believe celibacy has a lot of advantages if chosen voluntarily," he told CPR. "But the church should study mandatory celibacy to see if it's still the best way to go."

Advertisement

In recent years, Quinn took a keen interest in the plight of Native Americans, specifically the treatment they received during the Spanish colonization of California from 1769-1836. He believed the Franciscans, albeit with good intentions, did enormous harm to the native population, and he opposed the canonization of the missions' founder, Franciscan Fr. Junípero Serra.

"When I retired in 1993 I went to Tucson, Arizona, to work with the Tohono O'odham people" he told this writer in a 2016 interview at his retirement home in Sacramento. He intended to do pastoral work there for one year, but stayed 13, saying Mass, baptizing and doing counseling.

"I worked with the Franciscans," said Quinn. "I've always been friendly with them. As for the Indians, at first they were shy, but once we got to know one another they were warm and affectionate."

When Quinn returned to California in 2006, he was invited to say a Mass to commemorate the founding of San Rafael Mission near San Francisco. In his homily he apologized to the Miwok Indians and decried the destruction of their spiritual practices and punishments at the hands of the Franciscans.

"I've studied the Miwoks and I regret that they were treated unfairly," Quinn told the Catholic News Service. "They didn't expect an apology, so some of the Indians even wept. I looked upon it as a time of reconciliation."

Greg Sarris, head of the Miwok tribal council, told the Associated Press that Quinn's remarks were "historic."

Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band (provided photo).

In recent years, Native Americans and other scholars have taken a more critical look at the California missions. Scholar Sherburne Cook wrote that the indigenous population declined from 224,000 in 1769 to 150,800 by 1836, because of diet changes, epidemics, forced labor and slave-like labor conditions.

No figure has been more controversial in the missions than Serra, a native of Majorca, Spain, who founded nine of the 21 California missions. Pope John Paul beatified him in 1988 and Pope Francis canonized him in 2015, despite protests from Native Americans, several petitions and open letters to the contrary. Though personally austere spiritually and physically, Serra has been accused of authorizing beatings of the Indians, and he fought any attempts of the Spanish government to eventually allow the natives to govern the missions.

Historians such as Franciscan Fr. Francis Guest concluded in his book, Hispanic California Revisited, that "when a neophyte was whipped at a mission, he was, as a general rule, spanked rather than flogged."

But Professor Benjamin Madley of UCLA, author of An American Genocide, argues that the beatings were severe and that the missions were one of the greatest examples of mass incarceration in history.

"The missions did not have chain link fences, barbed wire, or guard towers," Madley wrote in the Pacific Historical Review. "But they used force to bring the natives to the missions, exploited their labor and restrained them with the use of shackles and stocks."

When Pope Francis announced plans to canonize Serra, he said that the Americas needed a role model and Serra fit the bill. Gov. Jerry Brown, a former Jesuit scholastic, supported Serra's sainthood, calling him "California's founding father and a very courageous man."

The Vatican has promoted an official biography of Serra by Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz of Santa Clara University. In remarks to the press, Senkewicz adhered to the Vatican's narrative, saying that Serra had flaws, but that in the long run, was a saint who did more good than harm to the mission Indians.

Bishop Quinn expressed his disagreement with that position in letters to Popes Benedict XVI and Francis.

In contacting the Vatican, Quinn worked closely with Dr. Donna Schindler, a California psychiatrist who works with Native tribes, and with Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, based in Central California.

"We reached out several times to the popes urging them not to canonize Serra, but all they did was offer us prayers," said Schindler, who specializes in intergenerational trauma. "Had they apologized, they would be forgiven. It would have been very healing."

Said Chairman Lopez, "We met with Bishop Quinn regularly. He referred to us as 'our team.' He said you don't evangelize with horses, weapons, armor and aggression, but as the parable of the Good Samaritan teaches us, with words, deeds and love. He was one of my best friends, and I loved him."

[Mark R. Day is a former Franciscan friar. He covered the West Coast for NCR in the early 1980s. He can be reached at: mday700@yahoo.com]