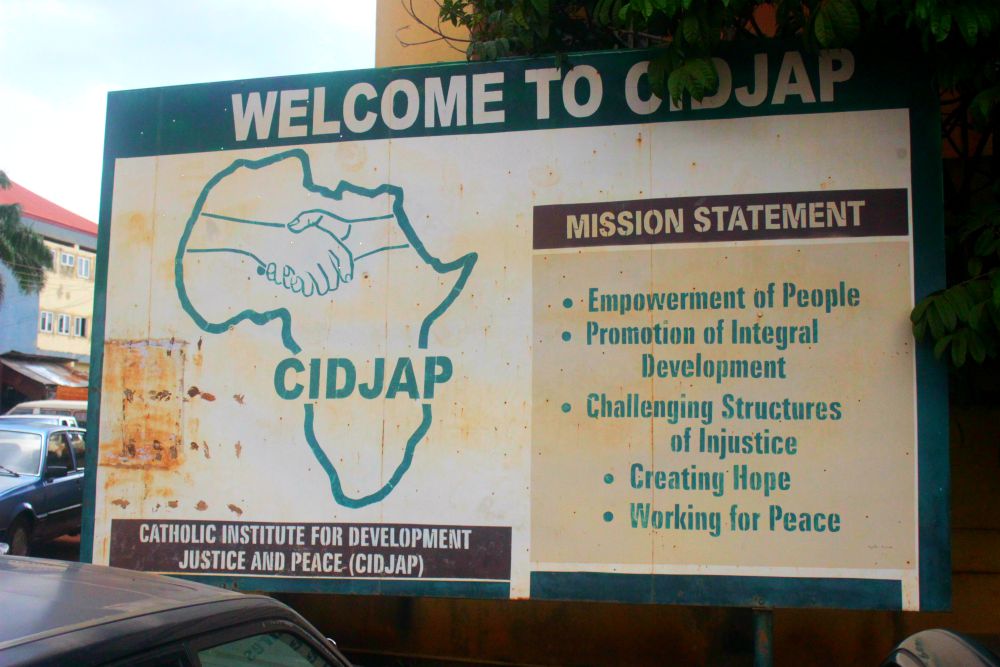

Building housing the Catholic Institute for Development, Justice and Peace, founded in 1986 in the Enugu Diocese (Patrick Egwu)

Susan John was two-months pregnant when she was arrested in 2016 and put in an overcrowded prison cell in Enugu State, in southeast Nigeria. She had been living with her boyfriend, who had committed a crime, and when the police came to arrest him, she was arrested, too.

Seven months after her arrest, she delivered a baby boy, Alexander. She remained in prison until recently, after a team from the Catholic Institute for Development, Justice and Peace (CIDJAP) visited her and other inmates who also had been awaiting trial for years.

"They (the CIDJAP) were the ones that got lawyers that took up my case and got me released," Susan John, 21 years old, said. "When I gave birth to my son, they brought us food, clothes and drugs through their welfare department."

Nigerian prison conditions have been described as deplorable, and the number of inmates awaiting trial who don't have access to attorneys is high. According to World Prison Brief, an online database providing information on prison systems around the world, the number of inmates awaiting trial in Nigerian prisons has risen from 62% of the prison population in 2000 to nearly 70%. The total prison population in 2000 stood at 44,450 but has risen to 73,248. The institute adds that the population of women prisoners within the period rose from 709, representing 1.9% in 2000, to 1,520, or 2.1% in 2019. The Enugu maximum security prison where Susan John was held was established in 1915 with a capacity for 648 inmates but now has more than 2,024 inmates, according to a report by the Nigerian Prison Service.

Catholic Institute for Development, Justice and Peace staff, from left: Fr. Chinedu Anieke, CIDJAP's director; attorney Chibuogwu Egbuna, head of the legal team at CIDJAP; and Daughter of Mary Sr. Chioma Onyenufoh, head of the CIDJAP welfare department (Patrick Egwu)

The Catholic Institute for Development, Justice and Peace regularly visits the four prisons in Enugu and others across the country to provide legal services to inmates. They also distribute welfare packages to the inmates and provide distress numbers people can call if they have family or friends held in police detention cells.

Founded in 1986 by Msgr. Obiora Ike and located in the Enugu Diocese, the institute has been advocating for justice, human rights and peace across Nigerian communities.

"We go there to take up these cases and move for motion for bail for the inmates," Chibuogwu Egbuna, the head of the legal team at CIDJAP, told NCR. "Sometimes, some of these cases are ongoing because they don't have defense counsel, and sometimes the judges write to us to come and take up the cases of inmates who do not have a counsel to stand for them during trial."

"What we do here is to take care of the welfare of the inmates in the prisons," Daughter of Mary Sr. Chioma Onyenufoh, who is in charge of the welfare department at the justice institute, said. "We interact with them so they can tell us their needs and we take notes."

Every week, on Tuesday and Thursday, the CIDJAP legal and welfare team visit prisons in southeast Nigeria and other parts of the country to assist inmates with their cases, especially those who have been abandoned by their relatives.

On Sundays, CIDJAP helps by celebrating Mass and sending holy Communion to the sick and other inmates in their prisons.

"When we get to the prison, we ascertain their case and pick it up from there," Egbuna said, explaining how the legal process works. "We file a motion, get their name and charge sheet before we proceed to the court that remanded them and get a record of proceedings. When you get to the proceeding, you attach it to your affidavit in support of the motion for their release."

Advertisement

The institute is working to get over 3,500 inmates freed from these prisons.

"Some of these cases are ongoing because they don't have defense counsel," Egbuna said.

"We work for the speedy dispensation of justice through legal advocacy, lobby and rehabilitation of inmates and ex-inmates," Fr. Chinedu Anieke, the director of CIDJAP, said.

Since the beginning of the year, CIDJAP has secured the release of about 20 prisoners across the country, and Egbuna said more inmates are in line to be released in the coming months. After inmates are released from prison, the institute's team helps them reunite with their families, especially those who served long prison terms and lost touch with relatives. After reconciling them with their families, the institute helps them to learn a skill or start-up a small business.

"I was in prison for more than two months on an awaiting trial list," David Chukwuma Aningene, a released prisoner, told NCR. "I was happy when they came to take up my case and rescued me."

The institute also intervenes to take care of inmates' health by providing routine drugs like pain relievers, vitamins and antibiotics. When Aningene, 42, was sick and needed to have surgery, CIDJAP's medical team stepped in and took him to the hospital where they paid about $553 for his medical fees. Recently, after an outbreak of a skin disease at one of the prisons, the CIDJAP team, alongside a team of doctors and nurses, visited the prison to provide drugs and carry out laboratory tests on more than 120 inmates.

Some challenges affect the works of CIDJAP in reaching out to thousands of prison inmates across the country. Every day, Onyenufoh reaches out to individuals and philanthropists in her local community for help and donations but only a few offer to help or make material donations.

"When we collect these items from those who donate to us, we distribute it to the prisoners in all the prisons," Onyenufoh says. "We make sure we give it to them directly so that the prison officials will not embezzle the items."

A sign posted at CIDJAP headquarters shows its mission statement. (Patrick Egwu)

For the past 30 years, CIDJAP prison projects have been largely sponsored by Misereor Germany — the German Catholic Bishops' organization for development cooperation. Every year, Misereor sends a team to evaluate and assess the prison projects. But Onyenufoh said multiple sources of donation and sourcing for funds will go a long way in reaching more inmates who need help across Nigerian prisons.

"We don't have a car to use in transporting some of the donations to prisons and we don't have money to buy one," Onyenufoh said. "Sometimes, we move from one parish to the other to ask for help so we can attend to the basic needs of the inmates."

Despite the challenges, Anieke said the "the motivation for what we do is based on one of the great commandments, to love your neighbor as yourself. We are called to love one another like Christ loves us, so we are fulfilling the scriptures and the word of God by helping these inmates."

Through a program called Education in Prison, the institute provides inmates education. When Susan John was in prison, she took her final secondary school examination and, in 2017, got admission to study primary education at the National Open University of Nigeria, which has a study center at the prison. She is currently a sophomore and expects to graduate in two years.

Susan John lost her parents when she was young. But she believes the education she's presently receiving will give her a better life.

"I am happy with the opportunity to go back to school," she told NCR. "I would like to be a teacher when I graduate so I can teach young girls like me what I didn't know at my age."

Editor's note: Susan John's name in this story was changed to protect her identity.

[Patrick Egwu is a freelance journalist based in Nigeria.]