BY JOHN L. ALLEN JR.

New York

If the job of, say, the Archbishop of New York, or Paris, or Milan, were vacant right now, much of the Catholic world would be on pins and needles waiting to see who will inherit a leadership role of such presumed consequence, not just for the archdiocese but for the entire Church.

Few members of the ecclesial chattering classes, on the other hand, are speculating about the next Archbishop of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo – even though one can make a very good case that the next occupant of that job will potentially have a lot more to contribute to the future of Catholicism.

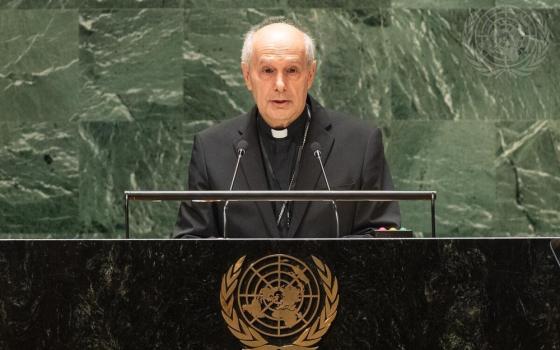

The post has been vacant since the January 6 death of Cardinal Frédéric Etsou-Nzabi-Bamungwabi, who was 76. Etsou became archbishop in 1990, during the final years of the famed dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, and he denounced the violence of the civil wars which raged in that era. Later, Etsou also rejected the anti-democratic tactics of Mobutu’s successor, Laurent Kabila, and he raised doubts about behind-the-scenes international influence in the victory last summer of Kabila’s son, Joseph, in national elections.

Congo is today a nation of 63 million, roughly 55 percent of whom are Catholic.

Broadly speaking, Etsou was the arbiter of moral legitimacy for any political force in Congo. Sometimes those forces would do whatever it took to secure his blessing, sometimes they broke with him, but always he was a factor in every political calculation in the country.

In this respect, Etsou was the prototypical Catholic prelate in Africa: blunt, unapologetically political in a way that would shock Northerners with their concepts of church/state separation, conservative on matters of faith but progressive on most social and political issues.

All of which might seem like a quaint local story, were it not for the fact that Africa is destined to be the powerhouse continent of the Catholic Church in the 21st century, and Congo is poised to emerge as the largest and most influential Catholic nation in the region. Whoever succeeds Etsou, therefore, will be setting a tone not just for Congo, but for the Church.

The phenomenal explosion of Catholicism in Africa deserves to make any “top five list” of the 20th century’s most under-appreciated stories, since it has reshaped the demography of the church in ways that we are only beginning to appreciate. Africa went from a Catholic population of 1.9 million in 1900 to 137 million in 2000, a staggering growth rate of 6,708 percent.

Given demographic and religious trends, this population realignment in global Christianity will continue.

Overall, by 2050 Africa will have a total of 342 million Catholics, according to Rogelio Saenz, a professor of sociology at Texas A&M University. That will make Africa the second largest Catholic continent on earth, behind only Latin America, with 646 million. Africa will have a substantially higher number of Catholics than Europe, with 255 million (that figures represents a decline from 270 million in 2004). Moreover, the rate of growth in African Catholicism will far outstrip the rest of the world, both because of higher-than-average fertility rates and because of the missionary success of the African Catholic Church. Today, more than half of all adult baptisms in Catholicism are in Africa, considered the best indicator of growth by conversion rather than birth.

In 2005, the ten largest Catholic countries in the world were:

1.tBrazil: 149 million

2.tMexico: 92 million

3.tUnited States: 67 million

4.tPhilippines: 65 million

5.tItaly: 56 million

6.tFrance: 46 million

7.tColombia: 38 million

8.tSpain: 38 million

9.tPoland: 37 million

10.tArgentina: 34 million

If one were to assume that the Catholic percentage in every country on earth will remain more or less constant for the next 43 years, then the same list in 2050, based on data from the United Nations Population Division, would look like this:

1.tBrazil: 215 million

2.tMexico: 132 million

3.tPhilippines: 105 million

4.tUnited States: 99 million

5.tDemocratic Republic of Congo: 97 million

6.tUganda: 56 million

7.tFrance: 49 million

8.tItaly: 49 million

9.tNigeria: 47 million

10.tArgentina: 46.1 million

Two European nations, Spain and Poland, will have fallen off the Top Ten completely, along with one Latin American nation, Colombia. In their place will be three African nations: The Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Nigeria. Congo has one of the highest total fertility rates in the world, at 6.07 children per woman of child-bearing years; that’s three times what it takes to keep a population stable.

Truth to be told, these projections almost certainly underestimate the African numbers, since the Church in Africa is growing not merely by birth but also through adult conversions. The Catholic population in African nations may be substantially higher in 2050 than these projections assume. Given that, it’s entirely possible that the Democratic Republic of Congo will have leapt past the United States and the Philippines to become the third largest Catholic nation in the world.

Brazil’s Catholic percentage, on the other hand, is going down, largely through losses to Pentecostal and Charismatic churches. It may well already be below 85 percent, which is the figure used in this projection. Likewise, the assumption that 78 percent of French will be Catholic in 2050 is almost certainly too high, especially if practice of the faith, rather than mere baptismal certification, is what’s meant by “Catholic.”

Hence this list should not be taken literally, but rather merely as indicative of broad trends. Even at that level, however, it’s an eye-opener in terms of the realignment of Catholic population worldwide.

Of course, population does not always equate with power, but over time it’s difficult to imagine that the rising Catholic tide in Africa will not translate into an increased voice in global Catholic affairs. In the 21st century, when one thinks of Catholicism in the “Third World,” it’s likely to be Africans who come to mind – and above all, the Congolese.

As Kinshasa goes, in other words, so goes the church.

One footnote: In recent years, it has become fashionable to dismiss French-speaking Catholicism as largely a spent force, despite the impressive character of some its leadership, such as Cardinals Godfried Danneels in Brussels and Jean-Marie Lustiger in Paris. Both France and Belgium have low Mass attendance rates, with 50 percent of the French reporting that they never attend religious services at all. A majority of the French, 51 percent, say they don’t even believe in God.

The rise of the Democratic Republic of Congo in global Catholic affairs, however, may give French-speaking Catholicism a new lease on life, in the same way that Brazil has long provided Portuguese bishops, theologians and lay activists with a disproportionate echo in the global church. French-speaking Congolese clergy and lay leaders naturally see France and Belgium as points of reference, reading the theological literature produced in French, inviting French-speaking Catholic VIPs to give lectures and host symposia, and otherwise regarding the French and the Belgians as primary sources of Catholic culture.

In that light, French-speaking Catholicism may have a future in the 21st century after all.

In the same spirit, it’s worth noting that by 2050, Uganda and Nigeria both will have grabbed spots on the Catholic “Top Ten” list, meaning that in 43 years four of the ten largest Catholic nations in the world will have English as a dominant language, as opposed to just two today. (In both cases, that’s including the Philippines). English is already the language of economic and cultural globalization, and increasingly it will become the language of ecclesiastical globalization as well.