(CNS photos/NCR graphic by Toni-Ann Ortiz)

"A retreat is a time to do nothing for as long as you can," according to Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk who attended many, directed several and complained about a few retreats at which his presence had been required. The retreat that might have been his most significant was one Merton had envisioned sharing with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Its proposed date — sometime in April 1968.

Stunned. That's how Merton recalled the nausea he felt April 4, 1968, when he heard on the car radio that King had been shot on the balcony of his motel in Memphis, Tennessee, just hours before. By the time Merton's driver arrived at the Abbey of Gethsemani, Kentucky, where the monk lived, King was dead.

A half century has passed since that brutal spring day. Pundits and pulpits alike postulate over what King would think of the progress — or not — made since his murder. How would he respond to the Black Lives Matter movement, to the gargantuan numbers of incarcerated American black men, to the barriers still in place for blacks and others in schools, housing and jobs?

For Catholics, indeed for all Americans, the 50th anniversary of King's death offers the chance to access how far the nation has come in its promise of liberty and justice for all, and how far it has yet to advance toward achieving the universal civil rights for which King labored and died.

Such weighty issues do not, however, annul a reflection on what a meeting between Merton and King might have looked and sounded like in that tumultuous year of 1968. For this reporter, who was privileged to see King twice and who has twice had the pleasure of visiting Merton's hermitage in rural Kentucky, the anniversary opens a window on what might have occurred.

I see these two men enjoying a smoke — Merton sucking on a pipe, King puffing a cigarette while occupying rocking chairs on the porch of Merton's simple cinderblock house. An odd pair of different ages, races, backgrounds and denominations, they seem a match on moral issues, conversing, deliberating, rocking.

Merton, the Catholic monk, had written often — mostly in letters and journal entries — about how excited he was to see the thrust of Christianity that King, the Baptist minister, brought to the civil rights crusade. Merton enthuses when he reads King's "Letter from a Birmingham Jail." He shares with his class of Gethsemani novices how the Birmingham, Alabama, marchers promised to find time for daily meditation on the life of Christ, and how they pledged that their nonviolent movement would work for justice and reconciliation, "not victory," an idea Merton praised.

A visitor sits in a replica of a jail cell next to a portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., in 2015 at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. (CNS/EPA/Tannen Maury)

The anniversary of King's death also presents an opportunity for scholars to take measure of this odd couple, as did Michael Higgins, who has authored three books on Merton. "Both men understood the power of a vision electrified by words, a vision biblical and epic in its range and yet grounded in the real," said Higgins, distinguished professor of Catholic thought at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut.

He pictured the twosome talking about Merton's friend, John Howard Griffin, author of Black Like Me, and perhaps reflecting on Merton's powerful poem on the slaughter of the children in Birmingham. They could also be conversing over what it is like "living in the shadow of an anger so fearful in its lethality that none are safe — especially prophets," said Higgins.

Both men knew they were living in a kairos moment at a providential time. Merton saw the civil rights drive as the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States. King named the race issue "America's greatest moral dilemma," one whose resolution "might well determine our destiny."

Certainly, such accord could have moved the two men to see what they could do to change the hearts of Americans at this urgent kairos moment. Merton termed it a merciful "moment of grace" and feared that it might pass without effect, turning into a dark hour of destruction and hate.

"I could hear the quiet reassurance of an inner voice, saying, 'Stand up for righteousness, stand up for truth. God will be at your side forever.' "

King, for his part, said nonviolence required active resistance to evil rather than passivity. It sought to convert, not to defeat the opponent; it was directed against evil, not against persons, wrote Princeton University emeritus religion historian Albert Raboteau in his book, A Fire in the Bones.

Nonviolence, for King, was based upon the belief that acceptance of suffering was redemptive, because suffering could transform both the sufferer and the oppressor. It was based upon loving others regardless of worth or merit; it was based upon the realization that all humans are interrelated; and it was grounded in the confidence that justice would, in the end, triumph over injustice, Raboteau wrote.

So it was not surprising that Merton, who also subscribed to a belief in redemptive suffering, should write a letter of condolence to Coretta Scott King just days after her husband's death, in which he says of King: "In imitation of his Master he has laid down his life for his friends and enemies."

Had they sat on the porch facing the tall wooden cross that famously marks a "you-are-here" spot at Merton's hermitage, surely these two men of prayer would have bowed their heads together. Near this symbol of compassion and reconciliation, they would have prayed aloud and in silence, wrapped in Scripture, or just spontaneously sat under the shadow of the green oaks or the starlit Kentucky sky.

It's likely that King would have heard of Merton's famed experience at the intersection of Louisville's Fourth and Walnut, in which the monk realized in a dazzling second that he was one with all the persons on the sidewalk, even though they were strangers who did not know they were "all shining like the sun."

Advertisement

We know Merton knew of King's own moment of conversion, described in Strength to Love, when, during a night rendered sleepless by a disturbing, harassing phone call, King left his bed to heat a pot of coffee.

I was ready to give up. I tried to think of a way to move out of the picture without appearing to be a coward. In this state of exhaustion, when my courage had almost gone, I determined to take my problem to God. My head in my hands, I bowed over the kitchen table and prayed aloud. The words I spoke to God that midnight are still vivid in my memory. "I am here taking a stand for what I believe is right. But now I am afraid. The people are looking to me for leadership, and if I stand before them without strength and courage, they too will falter. I am at the end of my powers. I have nothing left. I've come to the point where I can't face it alone."

At that moment I experienced the presence of the Divine as I had never before experienced him. It seemed as though I could hear the quiet reassurance of an inner voice, saying, "Stand up for righteousness, stand up for truth. God will be at your side forever." Almost at once my fears began to pass from me. My uncertainty disappeared. I was ready to go to face anything. The outer situation remained the same, but God had given me inner calm.

In that moment of epiphany in his Montgomery, Alabama, kitchen, King came to recognize that fidelity to his vocation required complete trust in God — in God's love, ability and desire, said M. Shawn Copeland, professor of systematic theology at Boston College. King knew God would sustain him in inner peace as he fought against the injustices of segregation, Copeland told NCR during an interview last June in upstate New York.

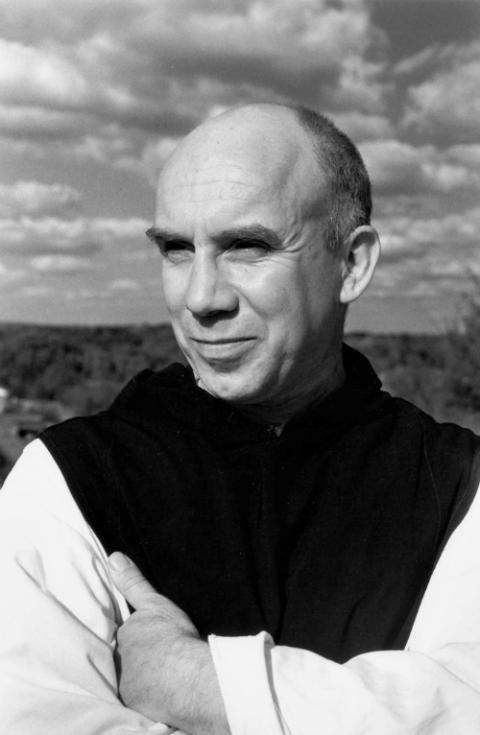

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Similarly, Merton came to recognize that his vocation was not for himself alone, but rather it was the "task of the monk to speak out of his silence and solitude" and to be a "witness" to the recovery and possibilities of human communion, she said.

The African-American theologian portrayed Merton and King as "the watchmen and the witnesses" in their exercise of the prophetic. Both men would have rejected the designation of prophet, she said, yet each man so attuned himself to the Word of God as to recover and to exercise the biblical vocation of prophecy. Copeland drew her characterization of the pair in a keynote address to the International Thomas Merton Society at St. Bonaventure University in Allegany, New York, last year.

King and Merton served as watchmen and witnesses in how they scrutinized the signs of the time and testified to God's care for the anguish of the world, she said. Each raised his voice in response to the "divine demand of conscience to speak a new vision to church and nation," one grounded in faith in God and in America's spiritual and political potential, Copeland said.

She pointed to the pair's like-mindedness in railing against militarism, war, racism and poverty. Their writings and protests were actions designed to heal "the broken bones of our body politic," to transform it into a beloved community.

Neither lived to see the result of his efforts. In eight months, Merton would be dead — electrocuted by a faulty fan in his room in Bangkok, where he was attending a meeting of Asian Catholic abbots.

"In imitation of his Master he has laid down his life for his friends and enemies."

"The murder of M.L. King ... lay on the top of the traveling car like an animal, a beast of the apocalypse," Merton wrote in his journal two days after King was killed. His death "finally confirmed all the apprehensions — the feelings that 1968 is a beast of a year. ... Is the Christian message of love a pitiful delusion?"

Perhaps King answered him in a telling line from one of his many rally speeches: "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter."

Fifty years on, these two spiritual brothers, who never met this side of the divide, still inspire us with their faith and activism.

Their retreat continues for as long as it can.

[Patricia Lefevere is a longtime NCR contributor who first met King in Milwaukee Jan. 27, 1964, while a student in the College of Journalism at Marquette University, and on April 27, 1967, on the St. Paul campus of the University of Minnesota, where she spoke to him about the Vietnam War.]