Dressed in yellow, the "Wall of Moms" in downtown Portland, Oregon, stand as a buffer between law enforcement and other protesters. (Courtesy of Maureen Markey)

"Keep Portland Weird" is an unofficial motto for Oregon's largest city.

It points attention to the city's reputation as a place young adults flock to for an engaging social scene, where incessantly rainy winters emerge into bright woodsy green vistas of summer, and with a work ethic that allows for the joke that the city is the place where 27-year-olds go to retire.

But not this year.

Portland, the whitest of large American cities, is now the unlikely epicenter of a struggle going on for more than 60 consecutive nights. Throughout late spring and this summer, Black Lives Matter protestors have engaged with police and, lately, with mysterious and controversial federal agents, sent to the city by President Donald Trump in a move that Oregon Gov. Kate Brown likened more to a pitch for law-and-order voters in Iowa and Ohio than to meet any security need. The Trump administration has said that the federal officers are needed to protect federal property.

Every night, police and protestors clash outside the Senator Mark Hatfield Federal Building downtown, named for a deceased Oregon politician who was elected during a different era, on an unlikely platform of near-pacifism and Republicanism.

And, in the most secular part of the country, religious Christians, most of them white and a portion being Catholic, have played instrumental roles in this year's protests. Yet their own official religious leader, Archbishop Alexander Sample, would prefer that they stay home.

Portland is a city of contrasts. Even before this spring's protests erupted after the murder of George Floyd May 25, Portland's progressive tendencies were apparent in the Black Lives Matter signs that dotted the lawns in the northeast section of the city, once known largely as a Black enclave, now gentrified with newcomers. It is the largest city in a state with a Klan operation that infiltrated its politics for much of the 20th century. Blacks are about only 6% of the city's population, with roots in an influx to the region during World War II to work in the region's armaments industry, filtering into the city after their settlement washed away in 1948. A powerful police union, say Portland activists, has prevented serious reform in the department, which in 2014 settled with the city to allow a police captain who was suspended for participating in honoring Nazis to get his job back with full back pay.

A woman in Portland, Oregon, holds a makeshift shield as she takes part in a demonstration against the presence of federal law enforcement officers July 21. (CNS/Reuters/Caitlin Ochs)

Some warn the frontier city is part of a new national focus, where wider political currents are being played out.

"Portland is at the center of the Trump administration's plan to destroy democracy," Melinda Pittman, an activist and long-time worker at a soup kitchen attached to St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in Portland, said about the presence of federal officers active on the streets.

Perhaps the most visible group of protestors is what's called the "Wall of Moms," adorned in bright yellow, conspicuously intended as a buffer to prevent officers from grabbing other protestors. In the phalanx is Maureen Markey, a Head Start school counselor and a member of St. Andrew Catholic Church in Portland, who comes at night wearing a bike helmet, goggles and a painter's mask that provide protection against both tear gas and the coronavirus pandemic.

She said she is there because her Catholic faith compels her.

"As Catholics, Black Lives Matter is so fundamental to what we believe in the sanctity of all life," she told NCR. "As Catholics, we are here to stand for racial justice. It's our birthright. I think it's fundamental. It should be a no-brainer."

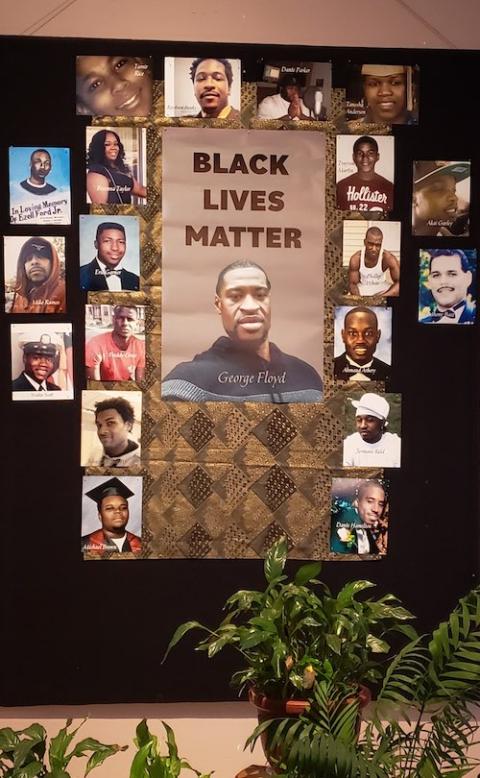

St. Andrew's church has become an unofficial center for Catholic activists. Its interior is decorated by a Black Lives Matter side altar that has a large poster of George Floyd and photos of other victims of police violence; and a sign supporting the movement stands outside the church. The parish youth group has organized its own demonstration, joined with adult parishioners.

A Black Lives Matter display at St. Andrew Catholic Church, Portland, Oregon, pays tribute to George Floyd and other victims of police. (Courtesy of Maureen Markey)

Another St. Andrew's parishioner involved in the protests and participating in the Wall of Moms is Maria Fleming, a teacher at St. Mary's Academy in Portland.

While there is a strategic reason for the Wall of Moms, seen as a barrier to possible police arrests in the crowds, Fleming sees the action as appealing to a maternal instinct.

"George Floyd called out to his mother. That was a call to all of us," she said.

Kate Anderson, another Wall of Moms participant and member of St. Andrew's, said that her presence, and that of the largely white crowd that gathers every night outside the federal building, is needed. The grandmother of three said that because white people are being tear gassed, there is more attention being paid to the goings on in Portland.

"It shouldn't be a political issue. People of color should be allowed to work and live their lives without a constant fear. That's not the case," she said.

While Fox News and the Trump administration highlight violent incidences, she said that the only act she saw that was violent — other than the police response to demonstrators — was a man spray painting a building. She told him to stop.

Participants in the demonstrations note that routine has emerged. Peaceful demonstrators crowd the streets until about midnight. And then the serious flareups begin. Sometimes the crowd shouts obscenities, which are responded to by the police in a similar way, particularly the federal officers, they say.

They agreed that the situation has become more enflamed since the emergence of the federal presence around the Hatfield Federal Building. That group, they say, is more likely than the local police to fire tear gas and smoke bombs at the crowd.

Portlanders note that, despite the images of violence seen across cable television news and social media around the country, most of the city is calm. One couple in northeast Portland, who live within four miles of the protests, noted that they would know nothing was happening in the city unless family from out-of-state reminded them of the images.

For Anderson, the community spirit of the protests, affirming the rights and dignity of Black people, is tied into her long commitment to Catholic-flavored activism. She said there is something stirring about the chants of "Black Lives Matter" that emanate from the largely white crowd.

Advertisement

Maureen Markey, left, next to another protestor holding a sign during a night of the Portland, Oregon, protests (Courtesy of Maureen Markey)

"You have to do something to be the presence of the divine in the world," she said.

Sabrina Sheehy, another St. Andrew's parishioner who is a member of the Wall of Moms, has seen the flash bombs and felt the tear gas delivered by the federal officers, who she said are apparently working separately from the local police.

"I feel like this is where Jesus would be," she said. "He went against the authority of his day when they spread injustice."

Still, while the Catholic activists see their faith as propelling them downtown, their official religious leader, Archbishop Alexander Sample, has not been a supporter.

Sample has largely been quiet about the protests, but he spoke up July 24 in a video address, his weekly "Chapel Chat" on the archdiocesan Facebook page, which is adorned with anti-abortion messages and promotion for natural family planning.

While the protesters see the police presence, particularly the presence of federal para-military forces, as the instigator, Sample described the protesters as fomenting "violent destruction that every evening results in looting and the destruction of property, clashes with police and federal agents. It's a mess, quite honestly."

In a free-form presentation titled "What's up with Portland?" Sample, who acknowledged his own discomfort in addressing the issue for fear it would be misinterpreted, said the continued protests are "about the riots, the destruction of property, the graffiti. Who remembers George Floyd anymore?"

He urged Catholics to avoid labeling political leaders and police officers as racist.

"[It is] the great work of the Evil One. He loves division," Sample said. "I pray that the protests in Portland will end soon." As an alternative, he urged parishes in the archdiocese to study the recent U.S. bishops' pastoral on racism, "Open Wide Our Hearts."

But it is unlikely that the protestors will heed Sample's plea.

"The Catholic Church in Portland is extremely conservative in the political arena," said Pittman, who, along with other protestors, expressed disappointment that Sample has not been more forceful in support of the Black Lives Matter cause.

Archbishop Alexander Sample of Portland, Oregon, speaks about ongoing protests in his city during a July 24 livestream of his weekly "Chapel Chat." (CNS/Courtesy of the Catholic Sentinel)

Tony Jones, chairperson of the executive committee of the African American Catholic Community of Oregon, helped to write a July 17 letter to Sample urging him to embrace an anti-racism agenda, via having more education of priests on racism issues, encouraging them to address racism from the pulpit, and promoting leadership roles for African Americans in the archdiocese.

A minority within a minority in Oregon, the Black Catholics group is looking at long-term solutions, Jones said.

"Our focus will be education," Jones said in an email to NCR. "We will continue to proclaim the good news of the Lord. That means speaking his message of loving our neighbors and its holistic meaning, including standing and interceding for one another."

Fr. David Zegar, pastor of St. Andrew's, told NCR he is proud of how his parishioners have responded to the Black Lives Matter movement, although he has not attended the protests because of his heart condition and health concerns about coronavirus.

"While I am supportive, I have a hard time to ask parishioners to go. It's not always safe," he said, referring to the lack of physical distancing inherent at the downtown protests.

About half of the parish is Latino, and some of them expressed concerns about the violence that sometimes erupts downtown. Other parishioners want to bring their children, but the sometimes vulgar chants, such as "F--- the police," make them uneasy. That's one reason, he said, the parish has supported a smaller Black Lives Movement demonstration outside the church, located a few miles from the protest site.

"People are engaged and concerned. They want a church that speaks to this issue," said Zegar.

Valerie Chapman, a retired pastoral administrator at St. Francis Parish, is immersed in organizing discussion groups and other forums to address racial justice concerns. The outpouring of support for Black Lives Matter, she said, provides a welcome contrast to the checkered history of Oregon on racial issues.

Now much of the attention is focused on the Trump administration's introduction of federal force.

"It was all settling down and then the Feds came in and riled it all back up," she said.

For Pittman, one concern is that Portland may not be so "weird" after all, that it will soon have company around the country. Trump has threatened similar federal interventions in other cities, including Chicago. Her language reflects much of the anger present in Portland activist circles, and she described the newfound federal interest in Oregon protests as illustrative of a fascist tendency in the Trump administration.

"I had no idea we had gone so far down in ignoring the Constitution," she said.

From left: Maureen Markey, Kim Keefe and Rafaela Steen during an evening protest in downtown Portland, Oregon (Courtesy of Maureen Markey)

[Peter Feuerherd is NCR news editor. His email is pfeuerherd@ncronline.org.]