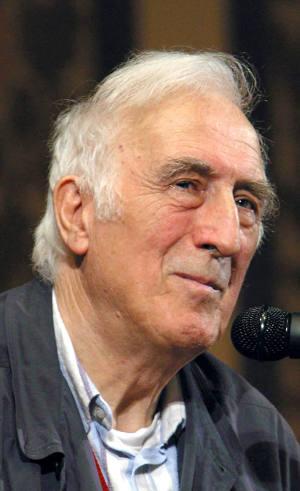

Jean Vanier, founder of the L'Arche communities, appears in the documentary "Summer in the Forest." (CNS/Abramorama)

Jean Vanier, 90, founder of L'Arche communities and co-founder of Faith and Light, died May 7. Vanier had been suffering from cancer and was assisted at a L'Arche facility in Paris.

In 2015, Vanier was awarded the Templeton Prize, viewed by many as the most prestigious award in the world of religion and spirituality. In October 2018, he received the Spiritual Solidarity Award from Adyan, a Lebanon-based foundation focused on interreligious studies and spiritual solidarity. In 1994, the University of Notre Dame presented him with its Notre Dame Award for worldwide humanitarian service.

He was the author of some 30 books, a member of the Order of Canada, and member of France's Legion of Honor, but he was perhaps best known as a kind of village elder to the world.

Vanier permanently changed the fate of intellectually disabled people everywhere by demonstrating how the care of a community could open lives to meaning, joy, hope and trust — not just the lives of the disabled, but the lives also of those who live with them and care for them.

"Jean Vanier's legacy lives on. His life and work changed the world for the better and touched the lives of more people than we will ever know," L'Arche Canada spokesperson John Guido said in a prepared statement.

Over the past year, Vanier gradually entered into the sort of frailty and weakness natural to his age, before entering palliative care in France in April.

In a visit to Chicago in 2006 to accept the Catholic Theological Union's Blessed are the Peacemakers Award, Vanier said he had noticed that people who have mental disabilities often have great faith, but they never speak of "Christ" or "the Lord."

"They always talk about Jesus," Vanier said. "It's a personal relationship."

In L'Arche communities, the disabled residents are seen as the "core members," and treated as individuals, with respect and love, and nondisabled and disabled residents alike learn to live together.

"Our danger is to see what is broken in a person, what is negative, and not to see the person," said Vanier. "It's not just a question of believing in God, but of believing in human beings, believing in ourselves, and seeing people as God sees them."

That means not relating to them from a sense of power, even if that power comes from generosity.

"Generosity is something that is good," Vanier said. "When we have more wealth, resources and time, we want to succor those in need, and that's good. But behind generosity is a notion of power. Generosity must flow into an encounter. We must meet people. It's not a question of doing for, but of listening to their stories."

The son of George Vanier, former governor general of Canada, and Pauline Archer, whose cause for sainthood as a couple remains active, Vanier was educated at boarding schools in England, France and Canada. Though his father disapproved, Vanier entered the Royal Navy at Dartmouth Naval College in England in 1942 and became an officer serving on various warships from 1945 to 1950. In 1949, the young officer transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy.

Jean Vanier, founder of the L'Arche communities, is pictured in an Oct. 28, 2002, photo. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Along with his military career, Vanier nurtured a deepening and very traditional Catholic faith — spending long hours at prayer on the deck of ships as he kept watch. By 1950, he felt he needed something more than his naval career could give him. He resigned his commission and began theological and philosophical studies, leading to his Ph.D. in philosophy from Paris' Institut Catholique in 1962.

From Paris, he moved on to teaching philosophy at St. Michael's College in the University of Toronto. But his academic career was still not satisfying his hunger for meaning. In the ferment of the Second Vatican Council, Vanier began to explore religious life guided by Dominican Fr. Thomas Philippe.

It was Philippe who urged Vanier to visit psychiatric hospitals in northern France. There he met institutionalized men with intellectual disabilities who were brutalized and neglected.

One of these men asked Vanier, "Will you be my friend?" From that moment, the international L'Arche movement of communities dedicated to people with intellectual disabilities began. With Raphael Simi and Philippe Seux, two formerly institutionalized men, Vanier established the first L'Arche ("The Ark") community in an unheated, tumbledown stone house at Trosly-Breuil, north of Paris, in 1964.

On Jan. 12, 1965, NCR first reported on Vanier's decision to dedicate his life to mentally challenged adults.

"We hope it will be like a Noah's Ark, to save those we can from the deluge of civilization," he said at the time, expressing his hope to open two additional houses to the ministry and create a "small village."

Speaking with NCR nearly four decades later in 2002, Vanier said the aim of L'Arche was not to change the world, "but to create little places … where love is possible."

He called the vocation of L'Arche one that is "revealing the face of Jesus to people in pain."

Advertisement

Vanier said that the mentally challenged were most in need of knowing God's love within them, and that they can only discover it through others. When that happens, "then I venture to say they are no longer handicapped. They may still have difficulty finding their place in society, but by knowing God's love, they discover their own personality and their real significance in the world."

He called L'Arche "a school of love" and that the personal relationships that its communities form is what has separated it from other institutions that care for mentally disabled people.

"With professionalism, they don't enter into a personal relationship with people with disabilities. Here, we want to enter into personal relationships," he said in 2014, the 50th anniversary of L'Arche, in an interview with the Los Angeles Catholic Worker's Catholic Agitator newspaper.

Speaking to The Catholic Register in 2018, Vanier seemed still surprised that this precarious experiment had grown to 147 communities operating in 35 countries for the benefit of approximately 10,000 core members.

"I began in a rather dilapidated house. I didn't realize it was something rather new," Vanier said in an April 2018 interview. "What I really see is the hand of God. Doors started opening. Money started coming. It was just the hand of God, as if somewhere the pain of God was somewhere that the littlest people, the weakest people were being rejected."

L'Arche's embrace of multiculturalism and interfaith communities began in Canada, particularly under the guidance of Fr. Henri Nouwen, the Dutch-born theologian who lived several years at L'Arche Daybreak in Ontario.

Over the years, Vanier was transformed by his own movement. From the tall, reserved, conservative and serious Catholic and former naval officer, he became the grandfatherly, twinkle-eyed friend of people who could never read his books and cared nothing about all his academic accomplishments.

"Living with people with disabilities is so simple. You have fun together," he told The Catholic Register. "They're not intellectual people. They're not people who are going to have big discussions about finance, politics, philosophy. They like to have fun."

"What’s important is that you be fully a human being. That means family, community, openness to others and commitment to and respect for the poor. This does not necessarily mean doing big things. But in the parish, it means being present to that little old lady who is alone."

— Jean Vanier

For Vanier, L'Arche became a continual learning experience. Living and working with mentally disabled adults, he said, became a way to prioritize people and enter into personal relationships.

"It has brought me into the world of simple relationships. It has brought me back into my body, because people with disabilities do not delight in intellectual or abstract conversation," he said in 2000, speaking to NCR after he addressed a millennium festival for young adults in Ontario.

The success of L'Arche and his ministry elevated Vanier within the Catholic world. He was good friends with Mother Teresa of Calcutta. He was seen often at the Vatican and met several times with Pope John Paul II. He accompanied the pope to Lourdes, France, where John Paul, at that point 84 years old and in declining health, gave Vanier the rosary he has used to pray earlier that day.

While some members of his movement expressed a desire to see Vanier canonized a saint, the Canadian deflected the idea. When asked about the possibility by NCR in 2002, he responded, "That's a way of destroying you. You know what Dorothy Day said about that."

"Jean Vanier's great gift was his amazing trust in people," St. Joseph Sr. Sue Mosteller, who worked with the L'Arche Daybreak community in Toronto for four decades, told Global Sisters Report earlier this year. "He trusted others to be responsible. Jean emphasized that when new projects were started, the organizers all have options. But if it fails, people with disabilities don't have options, and that's why we have to work hard to make sure we have a stable foundation."

Within and beyond L'Arche, Vanier celebrated the power within community. In a September 1985 interview with NCR, he criticized what he called "the world of the ladder."

"There are people at the top of the ladder and people at the bottom," Vanier said. "The lot of the culture is the help people struggle up the ladder, which is social promotion and so on. And then this creates a lot of inattention, a lot of fatigue. It's a very tiring effort to always get up to the top."

Fr. Fadi Daou, right, president of Adyan, and Nayla Tabbara, also of Adyan, present the Spiritual Solidarity Award to Jean Vanier, founder of the International Federation of L'Arche Communities, Oct. 6, 2018, in Trosly, France. Adyan is a foundation for interreligious studies and spiritual solidarity based in Lebanon. (CNS/courtesy Adyan Foundation)

The message of the Gospel, in contrast, he described as "to go down the ladder, to meet the poor, to accept our own poverty. It's not just a question of meeting the poor outside of us, it's also meeting the poor inside of us."

Vanier was critical of the desire in American culture to be autonomous and not dependent on anyone, which is said was out of line with the vision of Jesus "to create a body where there's interdependence. We need each other, and the needing of each other is the reality of love."

In his 2014 interview with the Catholic Agitator, he called individualism "the greatest evil of our time." Community, on the other hand, he considered "vital," and that friendship alone can overcome violence.

"And the problem of our time is that people don't want community," he told the Catholic Agitator.

Freedom, he said, derives from the values of community, not necessarily through society. He saw the path to freedom as an internal movement to see each person as a person.

"How do we help people to discover that the spirituality of Jesus is something quite simple?" he said in 2000. "It’s about being human, loving people and accepting people that are different. It’s about building community and learning about forgiveness, and about creating these centers of radiance, which is the parish."

Vanier saw the parish as central in creating community but also key in helping people become more human — a role he saw as integral for the Catholic Church and all Christian churches.

"What’s important is that you be fully a human being," he told NCR in 2000. "That means family, community, openness to others and commitment to and respect for the poor. This does not necessarily mean doing big things. But in the parish, it means being present to that little old lady who is alone."

Reflecting on death in the same interview, Vanier called it the role of those who are aging "to leave behind a vision, a spirit. Then to disappear."

"If we human beings have been able to just pass on a spirit, then we have accomplished our mission," he said. "If I love that person, then I have to continue to live, to be the person I am called to be. I must grow up. The danger with death is that we can hold on to the nostalgia of death. We didn’t want that person to die. So we remain closed up in grief and loss, instead of seeing what that person’s gift was and what has been given to us and to give thanks."

[NCR staff writer Brian Roewe contributed to this report.]