Montfort Fr. Francis Pizzarelli, Hope House's founder and leader for the past 38 years (Provided photo)

Just a short stroll from the marshes of Long Island Sound, the sounds of the vigil Mass before Ascension Thursday ring out from the tiny St. Francis chapel here at the Little Portion Friary.

It's not a feast day that usually attracts big Mass crowds, but there are more than 70 people here this May 10, nearly filling the chapel. The sounds of the St. Louis Jesuits and Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind" ring out from a nearly all-male choir.

The congregation includes some women from this North Shore Long Island area, some 55 miles east of midtown Manhattan, but there is an overwhelming male presence. They are the people of Hope House Ministries, people in recovery from addictions, largely those affected in the opioid scourge afflicting these suburbs. They end Mass with Hope House's anthem, calling out to "hold out your candle for all to see," an ode to self-affirmation.

They may appear to be a captive audience, but no one is forced to attend Mass. But the bulk of the Hope House residents are here, a recognition that for many people who have addiction, spirituality remains a vital link in the recovery process, whether it be Eastern meditation, Bible study or Catholic Mass. Hope House does not discriminate, either spiritually or in its approaches to addiction. Whatever works will find use here.

At the altar is Montfort Fr. Francis Pizzarelli, Hope House's founder and leader for the past 38 years, bedecked in sandals and a now-whitening beard. For decades, Pizzarelli prophetically shouted from his Port Jefferson, New York, base, that addiction was not only an issue in the urban core but also afflicted Long Island's suburbs. By now, his message has gotten through. No one seriously denies the problem anymore. But whether it is being taken seriously enough is another question.

Advertisement

Pizzarelli's voice has mellowed but still has a prophetic edge. "It is so out of control everywhere," he says in an interview from his office in Port Jefferson. The long-term issues emerge: The church has been moving too slowly to address the issues. The insurance companies set up people with addictions to fail because they try to get by with cheaper programs, like out-patient care or in-patient stays limited to 30 days. While President Donald Trump says he's on board in the struggle, there is a question about how much the federal government is willing to do. And the scourge continues. In Suffolk County, where Hope House Ministries is located, there were 360 opioid overdoses in 2016, more than two and a half times the number in 2010.

Curtis is 27 years old, from Connecticut, and is a resident of Hope House who knows that 30-day rehab stays don't do the trick. He admits to previous relapses from an alcohol and heroin habit that has at times nearly killed him.

"This place saved my life," says Curtis, divorced and the father of two, who says he's now closer to his ex-wife than they have ever been. He's been at Hope House for 20 months. His family will come on occasional visits across the Sound from Connecticut. But Curtis knows that the Connecticut town where he grew up is no place for him, as it is filled with contacts from his drug-using days.

Curtis talks about where he grew up, in a pleasant town with a devout Catholic family. He was homeschooled. While eating dinner, cooked by volunteers from the area, Curtis and the other 50 residents listen as Tom, a counselor and graduate of the program, goes over some of the rules.

Keep your room clean. Don't keep the laundry room window open overnight or else the raccoons may decide to nest there. No sodas brought back to the rooms. Time in bedrooms cannot exceed more than an hour, until bedtime, at 11 p.m. on weekdays. Prescriptions will be parceled out in a half-hour time frame.

Other rules aren't spelled out at this dinner but are well known to the residents: no alcohol, no women visitors and, of course, no illegal substances.

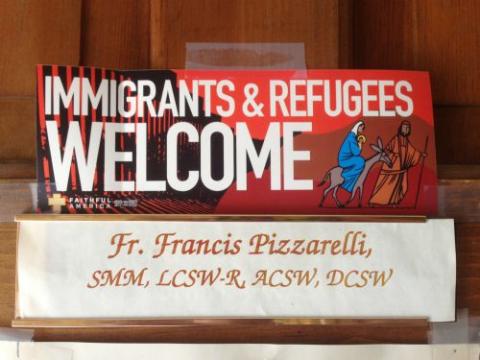

Sign outside of Fr. Francis Pizzarelli's office at Hope House (Peter Feuerherd)

Larry, 26, a resident here for more than three years, is one of the many residents from Suffolk County on Long Island. He was sent by the courts after being charged with DWI. He attends Suffolk Community College, where one of his professors is Pizzarelli, who also teaches at nearby St. Joseph's College and at Fordham University, where he arranges scholarships and aid for Hope House residents.

For the general public, used to hearing about Hollywood stars entering and re-emerging after short rehab stints, Larry's three years here might seem like a long time.

But one of the pluses of Hope House is that all its residents, as long as they obey the rules, will not be sent away. And they stay free-of-charge. "You can stay as long as you want. He will not kick you out," says Curtis.

Before coming to Hope House, Curtis said he was lacking in hope. "You want to die," he says about his life as an addict. "But there's still a shred of hope you are clinging to."

"I had no relationship with my kids. No relationship with my family. No one wanted to do anything with me anymore," he says.

Tom, who now works at Hope House after living as a resident, said that he came here in 2005, and the nature of the place has changed. Before, there was much emphasis on homelessness, the situation he found himself in as a young man (he is now 30). Today's opioid overdose crisis means the ministry is geared to rehabilitation, with days filled with counseling sessions, work on the grounds of the Hope House buildings spread out around the area, and therapy. Days begin at 7 a.m. and continue through 11 p.m. with lights out.

Residents range in age from 17 to 45. They come from as far away as Harlem and, in Curtis' case, Connecticut, but most are from Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island. Some come with important jobs, which they drop upon gaining entrance.

Pizzarelli has endured much through Hope House's 38 years. Its property base has expanded as its mission has, 11 facilities serving both men and women, all located in and around Port Jefferson, the town where Pizzarelli began his ministry at Infant Jesus Church. Facilities now include a men's shelter, counseling center, an academy for troubled youth, an alternative high school, a home for women who have survived domestic abuse, and an addictions treatment center.

For years, Pizzarelli was often called to account for nearly every youthful panhandler or miscreant around Port Jefferson, who would be connected in the public imagination as being associated with Hope House Ministries. That has abated. His last public meeting, after Hope House Ministries bought an old Anglican Franciscan priory, focused on the trees on the property. Pizzarelli pledged not to cut them down. Town residents are regular patrons at the Hope House Ministries bakery, a business where residents work. Some of the area's Catholics seek out Mass at the facility.

While public and private officials decry the growing severity of opioid use, Pizzarelli says there's still a frequent lack of urgency. "The corrupt insurance lobby is paralyzing families everywhere," he says, noting that insurers' reluctance to pay for treatment literally results in deaths.

He is working with the local Diocese of Rockville Centre to declare a special weekend focus in parishes on addiction, including talks and information at all Masses, at a date yet to be determined. There's a need for mental health awareness: Many of the Hope House residents he lives with suffer from more than addiction issues. Some are carrying the burden of being sexually abused, for example. All this treatment takes time, and Hope House Ministries has become known for allowing residents all of that valuable commodity that they may need.

A trained social worker, Pizzarelli says the time is needed. Sometimes it will take seven months before a resident is able to benefit from counseling, for example.

Fr. Francis Pizzarelli adds a message to a graffiti wall in Belfast, Ireland (Provided photo)

"I have the rich and the famous. And the poorest of the poor," he says, noting that the impact of addiction is similar. "They all struggle with the same issues. They get better at a different rate."

His presence among them is a plus. While he spends a large part of his time on college teaching and fundraising, he always returns to the Hope House residence. "I live with them and I talk to them every day. I know the guys who are making it, and those who are faking it," he says.

Spirituality is integral to the Hope House Ministries. His role as a priest solidifies that aspect. Religious faith is a unifier, even as it involves Catholics, Protestants, Jews and those of no explicit tradition, all of whom have lived at Hope House. His long tenure as a celebrant in local parishes is also a plus, providing a connection where residences such as Hope House Ministries' were long viewed with suspicion, sometimes seen as public nuisances and a threat to property values.

"I've married them, baptized them," says Pizzarelli. "And I have taken care of their kids in trouble." That last duty continues unabated, bringing more future residents to the doors of Hope House Ministries.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and is a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]

We can send you an email alert every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.